Comoediae viginti nuper emendatae. Et in eas: Pyladae Brixiani lucubrationes. Thadaei Vgoleti et Grapaldi virorum illustrium scholia. Anselmi Epiphyllides.

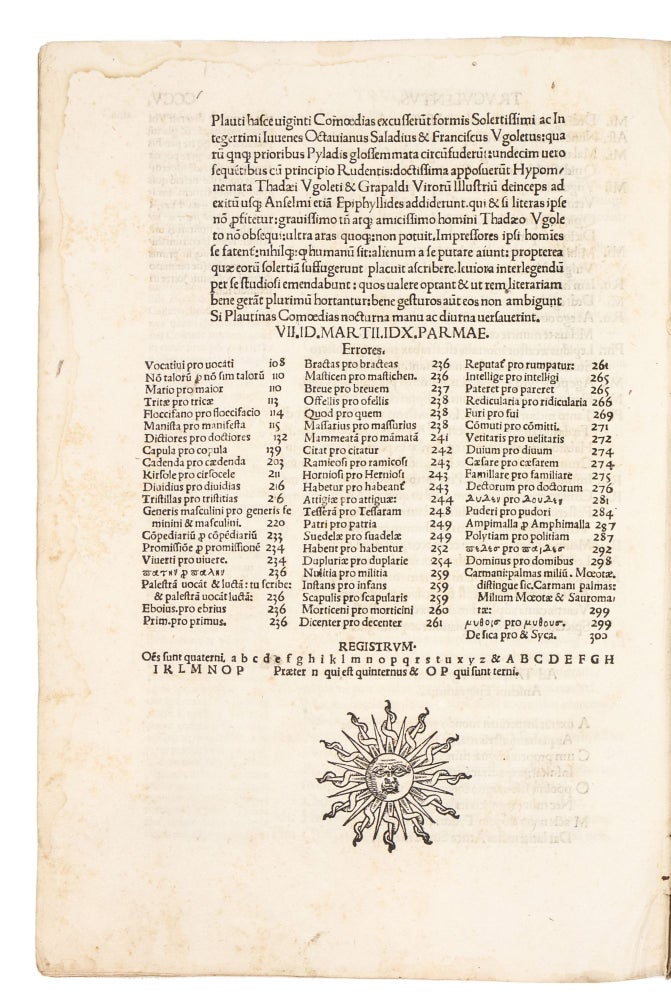

Parma: Octavianus Saladius et Franciscus Ugoletus, 1510.

Price: $10,500.00

Folio: 31.5 x 22.2 cm. 8, 310 lvs. (misnumbered). Collation: chi8, a-m8, n10, o-z8, &, A-M8, N-O6 (-blank leaf O6)

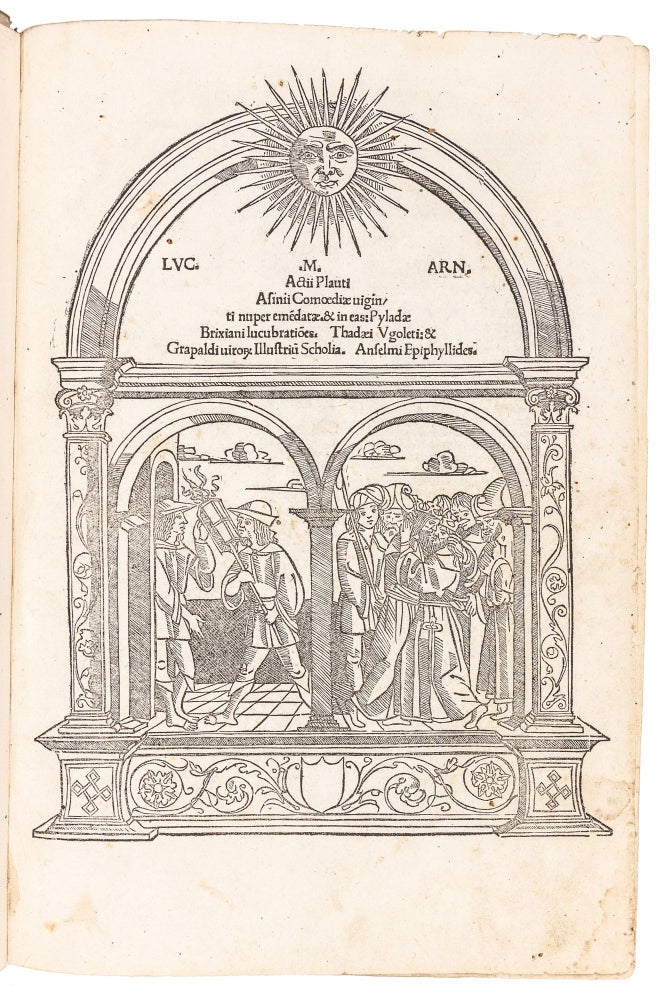

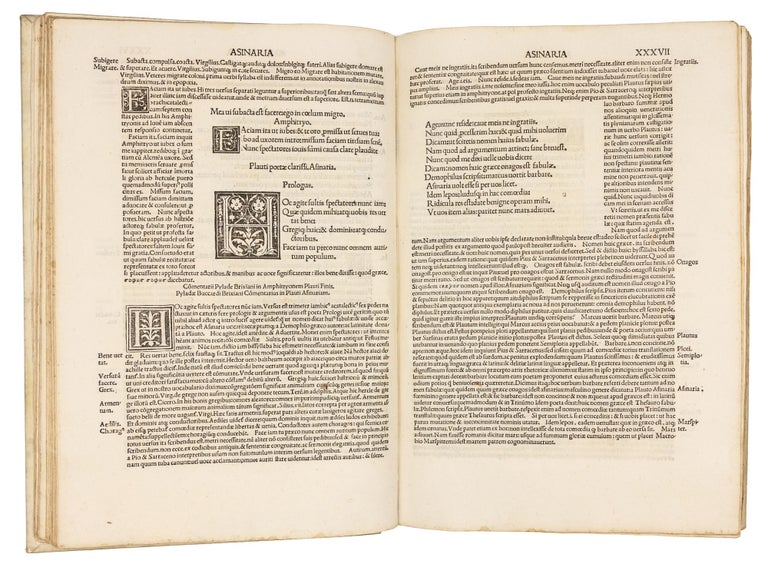

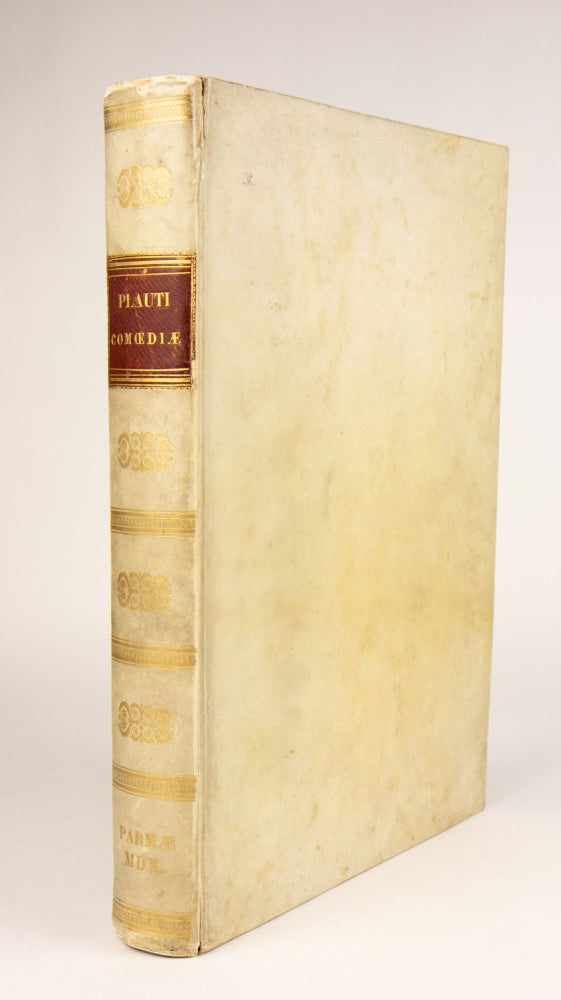

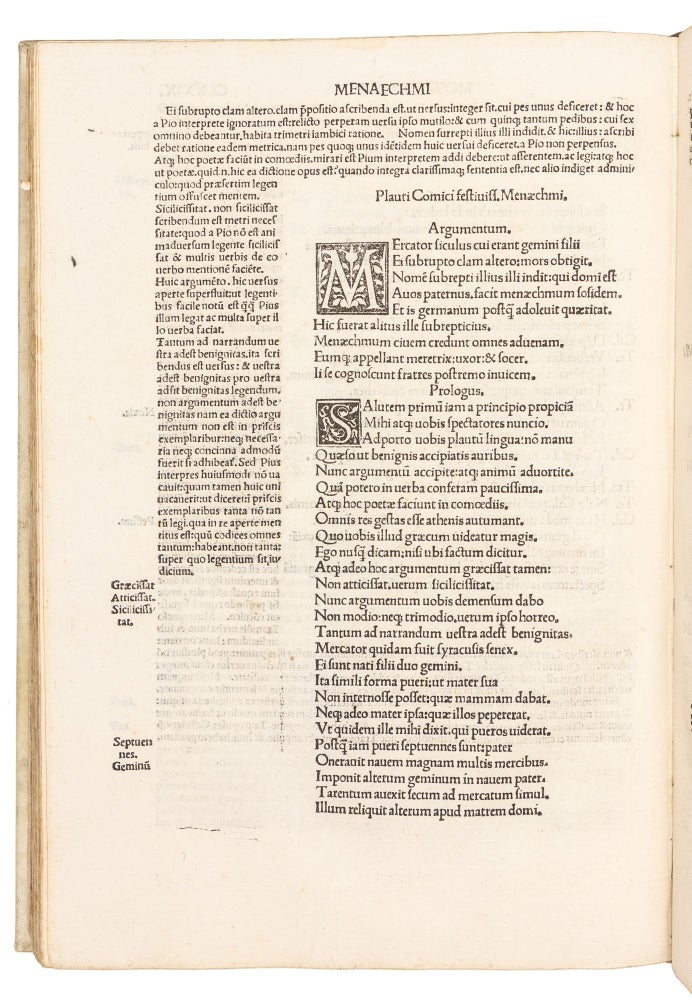

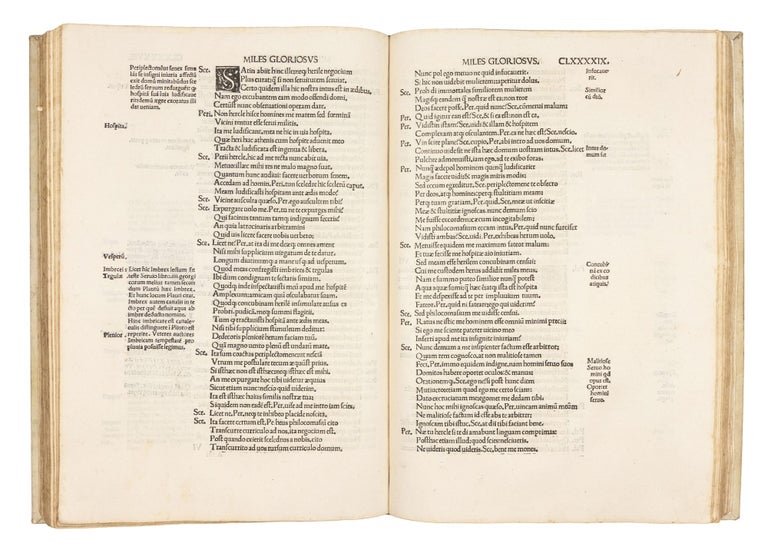

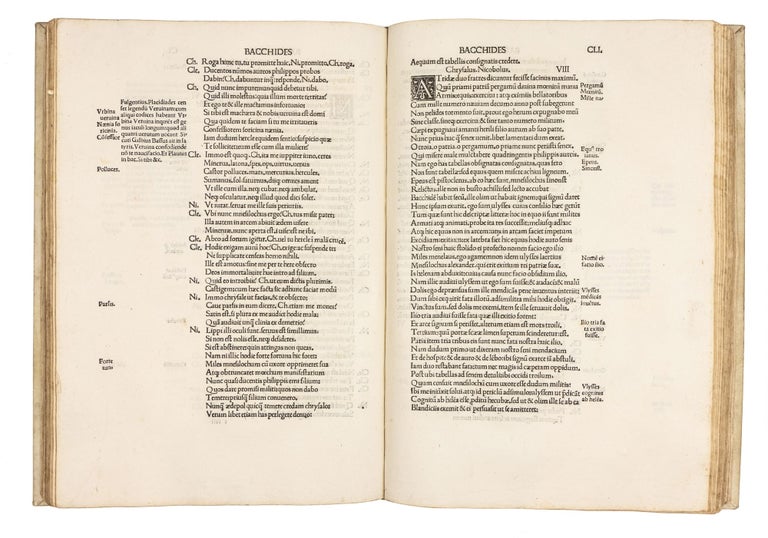

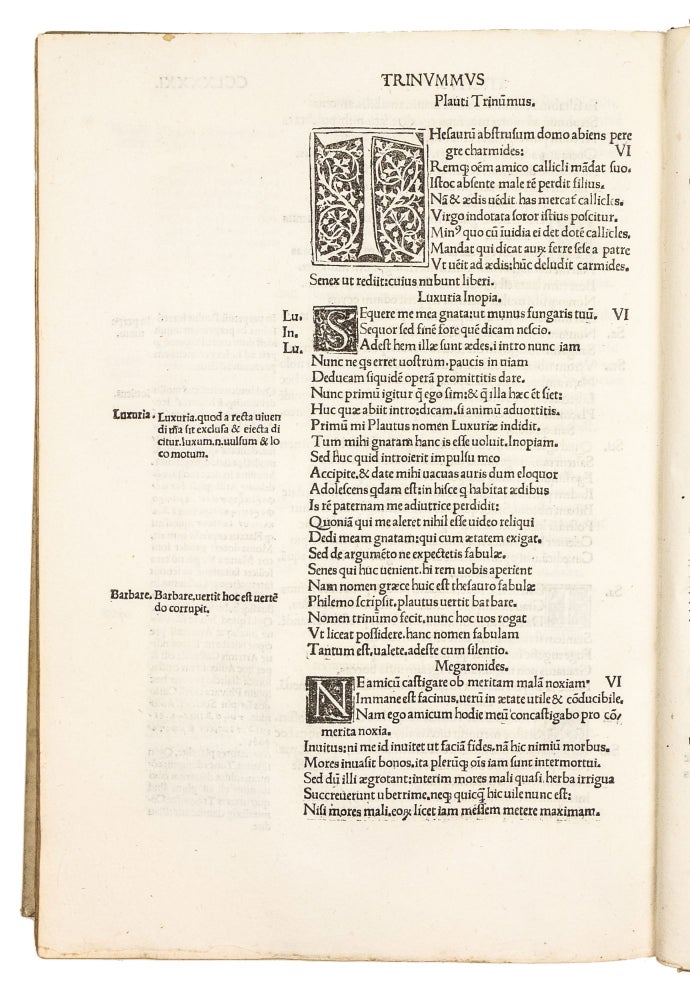

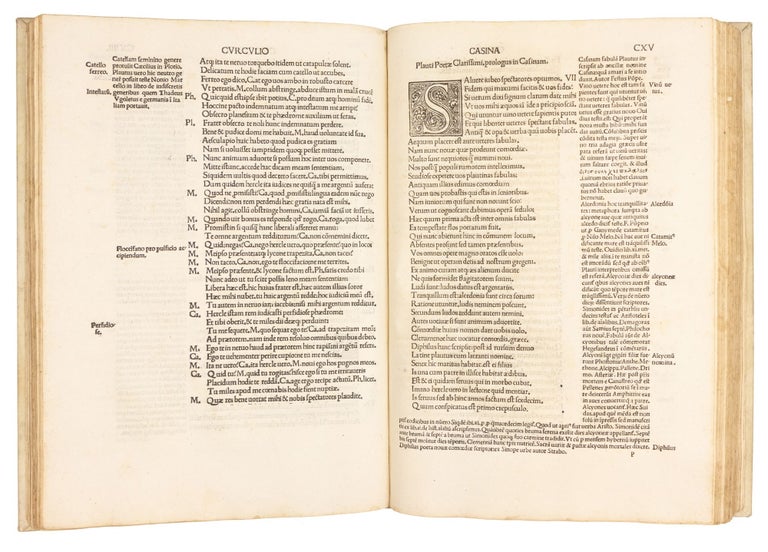

Bound in 19th c. ivory vellum, spine gold-tooled and with red Morocco label (small splits at head and tail of joints.) An excellent copy with wide margins. Outer margin of first few lvs. lightly soiled, the last few leaves with a light damp-stain in the outer margin, a few trivial marks, else very clean and attractive. Woodcut initials at the beginning of each play. Full-page woodcut scene on title page. Woodcut sun device on final leaf. Leaf Liiii with some Greek text.

The 1510 Parma edition of Plautus' comedies, important for the beautiful full-page woodcut frontispiece -the first printed illustrations of Plautus' plays. The architectural structure, with mullioned window, frames two episodes from the comedies: on the left, there are two young men, one of whom carries a lantern; to the right, two men embracing surrounded by a crowd of bystanders. The first image illustrates a scene from the play “Amphitruo”, in which Mercury, disguised as the slave Sosia, encounters the real Sosia in the doorway of Amphitruo’s palace. The second shows the Menaechmi twins, who have just discovered each other’s identities.

Above these scenes is a sun emblem, which is echoed by a similar woodcut on the final leaf. The only previous illustration to appear in an edition of Plautus (a Milanese edition published by Scinzenzeler ca. 1495), depicts not a scene from a play but only, in a small vignette at the end, the game of kottabos (cf. Sander 5746).

The text of Plautus’ plays is accompanied by commentaries by Gianfrancesco Boccardo (“Pylades Brixianus”) (d. 1505), Tadio Ugoleto (1448-1513), and Francesco Grapaldi (1464-1515); and poems (Epiphyllides) by Giorgio Anselmo (1459 - 1528). The book was printed by Ottaviano Saladi and Francesco Ugoleto.

“The comic playwright Plautus authored his fabulae palliatae (Roman adaptations of Greek comedies) for the stage between c.205 and 184 B.C. His works have the distinction of being the earliest Latin works to have survived complete. Varro drew up a list of 21 plays which were generally agreed to be by Plautus, and doubtless they are the 21 transmitted in our manuscripts.

“The plays are nearly all either known or assumed to be adaptations of (Greek) New Comedy, with plots portraying love affairs, confusion of identity and misunderstandings. Plautus adapted his models with considerable freedom and wrote plays that are in several respects different from anything we know of New Comedy. The musical element is much increased. The roles of stock characters such as the parasite seem to have been much expanded. Consistency of characterization and plot development are sacrificed for the sake of an immediate effect. The humor resides less in the irony of the situation than in jokes and puns. There are ‘metatheatrical’ references to the audience and to the progress of the play, or explicit reminders that the play is set in Greece. Above all, there is a constant display of verbal fireworks, with alliteration, wordplays, unexpected personifications, and riddling expressions (e.g. Mercator, 361, ‘My father's a fly: you can't keep anything secret from him, he's always buzzing around’). Both the style of humor and the presentation of stock characters may well have been influenced by the native Italian farces (‘atellana’), but the verbal brilliance is Plautus' own…

“Plautus' plays continued to be performed with success at Rome at least until the time of Horace, and they were read by later generations. The earliest surviving manuscript is the 6th c. ‘Ambrosian palimpsest’. Plautus was well known in Renaissance Italy, particularly after the rediscovery of twelve plays in a manuscript found in Germany in 1429, and his plays were performed and imitated all over Europe until the seventeenth century, and more sporadically thereafter. Terence was more widely read in schools, but both contributed to the development of the European comic tradition.”(Brown, Plautus, Oxford Classical Dictionary)

“The plots show considerable variety, ranging from the character study of Aululāria (‘The Pot of Gold’) (the source of Molière's L'Avare) to the transvestite romp of Casina, from the comedy of mistaken identity in Amphitruo and Menaechmi (both used by Shakespeare in The Comedy of Errors) to the more movingly ironic recognition comedy of Captīvī (‘The Prisoners’, unusual in having no love interest). Trinummus (‘The Three‐Pound Coin’) is full of high‐minded moralizing; Truculentus shows the triumph of an utterly amoral and manipulative prostitute. In several plays it is the authority‐figure, the male head of the household, who comes off worst. Some plays glorify the roguish slave, generally for outwitting the father. These plays have been seen as providing a holiday release from the tensions of daily life, and their Greek setting must have helped: a world in which young men compete with mercenary soldiers for a long‐term relationship with a prostitute was probably quite alien to Plautus' first audiences, a fantasy world in which such aberrations as the domination of citizens by slaves could safely be contemplated as part of the entertainment.”(Oxford).

Sander 5747. Schweiger II, 760. Adams P-1480. For the woodcut title page see M. Festanti, E. Zanzanelli, “Alle origini del libro moderno. Dal manoscritto al libro a stampa tra Quattrocento e Cinquecento nelle collezioni della biblioteca Panizzi”, Reggio Emilia 2012, n° 26.