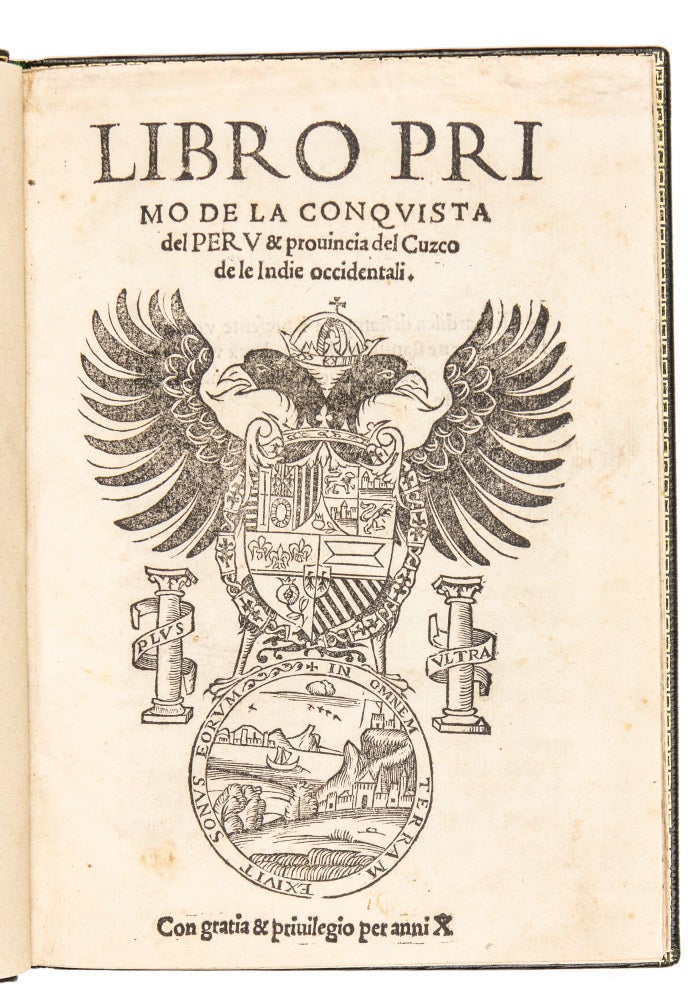

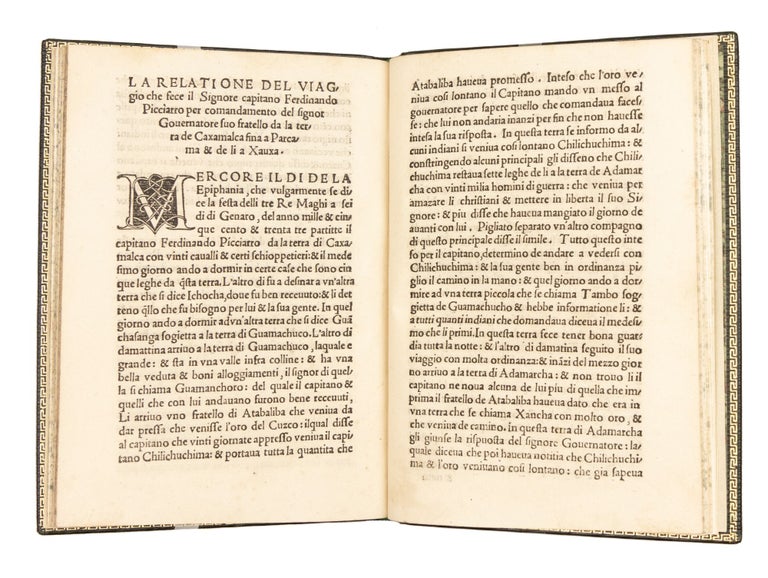

Libro primo de la conquista del Peru & provincia del Cuzco de le Indie Occidentali.

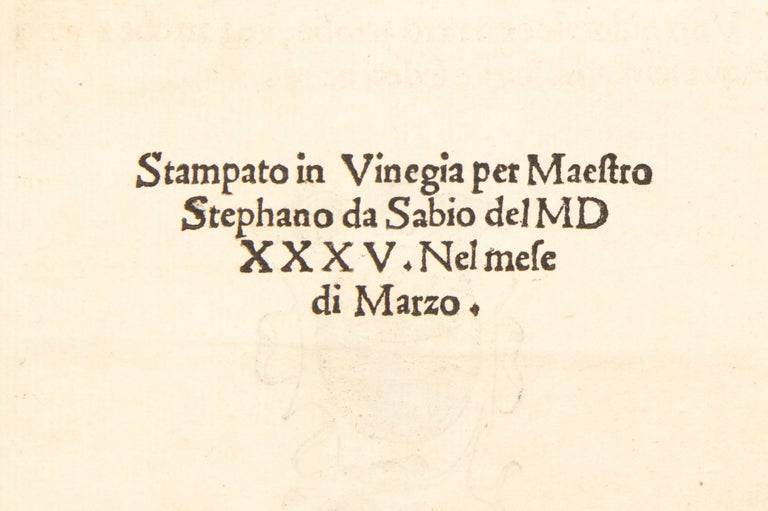

Venice: Stephano da Sabbio, March, 1535.

Price: $30,000.00

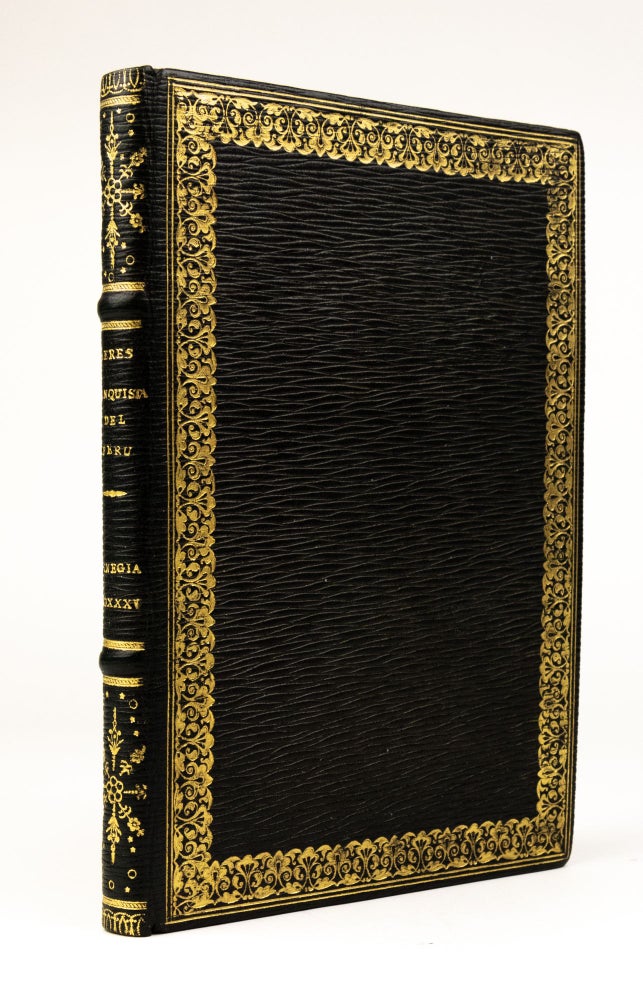

Quarto: 19.5 x 14.5 cm. [62] lvs. Collation: π4, a-f8, g10

FIRST ITALIAN EDITION (The first ed., in Spanish, appeared in 1534).

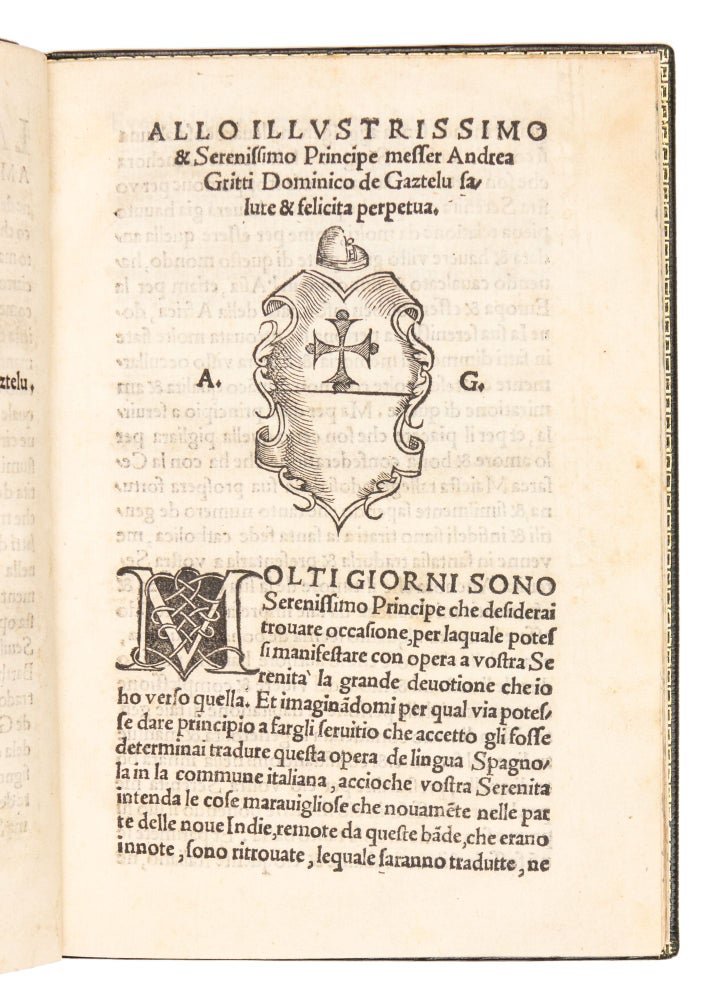

Bound in fine 20th-century dark green long grained morocco, boards framed by an ornamental roll, gilt. Gilt spine and turn-ins. A very good copy, edges sprinkled blue. Small, discreet repair to blank upper margin of t.p. and lower blank corner of 2nd leaf; small stain at upper corner of 4th leaf; gathering ‘e’ possibly supplied. Title with large woodcut of the imperial arms of Charles V; woodcut cartouches with the arms of Andrew Gritti (leaf 3r) and of the translator, Domingo de Gaztelu (leaf 2v).

First Italian edition of Francisco de Xerez’ eyewitness account of Francisco Pizarro’s expedition to conquer the Inca Empire, one of the most important accounts of the conquest of Peru. “Xerez’s work had a profound and lasting influence on all subsequent histories of Peru, and the ‘Verdadera relacion’ is widely regarded as the foundation of all texts dealing with the region and its conquest” (Delgado-Gomez 23, 1st ed.).

Born in Seville in 1495, Xerez arrived in New Spain in 1514 as a member of Pedro Arias de Ávila’s expedition. He explored the Isthmus of Panama and participated in Pizarro’s first (abortive) expedition to South America in 1524. In January 1531, Xerez set out once again with Pizarro on the fateful expedition that would spell the end of the Inca Empire.

Xerez actively participated in the capture of Inca Atahualpa at Cajamarca on November 16, 1532. During the battle between the Inca warriors and the Spanish, Xerez’ leg was broken when his horse fell on top of him. The fracture forced him to rest for months, a period in which we can assume Xerez began writing his account of the expedition, probably at the behest of Pizarro himself.

Xerez returned to Spain in June 1534 with the first installment of Inca gold. His book, “The True Account of the Conquest of Peru” was printed at Seville in that same year.

The importance of the book was amplified by the inclusion of another eyewitness description of events not witnessed by Xerez’, namely, Miguel de Estete’s account of Hernando Pizarro’s journey from Cajamarca to the Inca temple of Pachacámac, where the conquistadors toppled the cult statue, and then to Xauxa (Jauja) (fols. 43 to 55).

Both texts were quickly translated into Italian by Domingo de Gaztelu (1515-1547), who worked from the text of the second edition of the Spanish text (also 1534).

Pizarro’s Expedition and the Conquest of the Inca:

“Around January 1531 an expedition of three ships, perhaps 180 men, and some thirty horses left Panama with Francisco Pizarro in command. Within a short time the men were in the vicinity of the north Ecuadorian coast, but upon landing they found the first Indian towns deserted. They advanced to a large settlement called Coaque, which they attacked and occupied, taking a profit in gold and silver pieces. This treasure Pizarro sent to Panama and Nicaragua in the ships, which were to bring back reinforcements. To await them, the expedition settled down in Coaque for several months; many of the men fell victim to a strange disease which caused walnut-sized growths on their faces and bodies. At last a ship came from Panama bringing supplies, the three royal treasury officials, possibly twenty-odd men, and about thirteen horses. Thereupon the main body advanced south by land.

“They had gone only as far as Puertoviejo when two ships appeared on the coast with news that a party of about thirty men and twelve horses, under Sebastián de Benalcázar, had arrived from Nicaragua and was proceeding toward them by land from the north. In a few days Benalcázar's men joined the main group and were well received, though there was some grumbling at their small number. Apparently this was not the large party expected from Nicaragua.

Puná and the Arrival of Soto:

“As the expedition worked its way painfully down the coast, still suffering from diseases, it came near to the large island of Puná, in the gulf of Guayaquil. Seeking a place of recuperation and refuge from seasonal rains, the Spaniards crossed to the island, but they chose poorly, for the Indians of Puná gave them some of the hardest fighting of the whole campaign. The greatest event of the stay on Puná, however, was the expected arrival from Nicaragua and Panama of Hernando de Soto's party: two ships, perhaps a hundred men, and twenty five horses. With this reinforcement the expedition prepared in February, 1532, to return to the mainland and enter Inca territory.

“Túmbez had been the most impressive settlement that Pizarro and the men had seen in their 1528 reconnoitering; the intention now was to make it the capital of Peru, and several men on the expedition already had royal appointments to the council of the future city. But epidemics and a war with Puná had since ravaged the region, which seemed dry and without mineral wealth, in any case. For several months the expedition occupied the Túmbez region quite uneventfully, then after a time of exploration headed south to look for a better place to found a city.

“The Spaniards were now beginning to see Inca highways, herds of livestock, and warehouses. They met no more resistance than occasional skirmishing, flight, or rebellion after submission. The place they chose for a settlement was San Miguel (Piura) about a hundred miles south of Túmbez, thought to be well-watered, populous, and not far from a good port. Some forty Spaniards -the older, weaker, and in firm- became citizens and received encomiendas in the area. The rest, hearing of the Inca emperor's presence at Cajamarca in the highlands, set out to encounter him.

“During their ascent the Spaniards were often mystified or made suspicious, but never attacked. In the afternoon of November 15, 1532, they made an unmolested entry into the deserted central square of Cajamarca. Emperor Atahuallpa and his thousands of followers were encamped some distance away at a spring. The governor sent out Hernando de Soto and some of the best horsemen, whose mission it was to invite the emperor to visit the Spaniards, with the intention of capturing him according to standard procedure. Soto was not long gone when Pizarro had misgivings about sending such a small group, and sent another of the same size under his brother Hernando. Exactly how many men went, and what was said, has been obscured by greatly varying reports, but to have ridden on the mission was a feather in a man's cap. After making the Spaniards wait, Atahuallpa agreed to come to the Spanish camp the following day.

“The morning of November 16 found the Spaniards prepared to assault Atahuallpa whenever he should appear before them. Most of the some sixty horsemen were distributed in three large buildings on as many sides of the square, under the captaincy of Soto, Benalcázar, and Hernando Pizarro. A few others supported Governor Pizarro and some twenty-five footmen in a building on the fourth side. Perhaps seventy footmen were posted in small detachments to guard the several entryways to the enclosed square. Pedro de Candía, with a few artillerymen and musketeers, was atop a fortress that lay either in or on the square. At the proper moment, Pizarro's ensign was to hoist his standard, upon which the trumpets would sound, the artillery would fire, and the onslaught would begin.

“From earliest morning Atahuallpa had begun to move his thousands. Messengers went back and forth, saying first that Atahuallpa would come unarmed, then that he would bring weapons, while Pizarro replied that it made no difference -perhaps the truest word uttered that day on either side. It was late afternoon before the Inca's forces, filling the fields, came to rest some hundreds of yards from the square.

“Again Atahuallpa needed persuasion to come farther, and Spaniard Hernando de Aldana visited his camp. At last the emperor advanced toward the square, his following now reduced to a few thousand. The Spaniards were impressed by the hundreds of nobles who accompanied him in checked livery, singing in unison while they swept away straws and pebbles in his path. The Indians were armed, but only with small maces and slings. Once the whole entourage was inside the square, the Dominican fray Vicente de Valverde came out with an interpreter to speak to Atahuallpa. The Spanish intention, standard in such cases, was to get the chieftain into their power peacefully if possible. Words passed between the two, but Atahuallpa soon became agitated, and Valverde returned, shouting.

“At this the signal was given and the attack began, though not quite as planned, since not all the guns went off, and, when the Spaniards rushed out, many of the inexperienced footmen around the governor became frightened and fell to one side. Nevertheless, Pizarro and those remaining pressed into the crowd of Indians toward the litter of Atahuallpa. Miguel Estete de Santo Domingo is said to have first laid hands on him, and Pizarro himself to have taken him prisoner. Meanwhile the horsemen were having the effect of an earthquake on the mass of Indians inside the plaza. Many were trampled, and others trampled each other, until by sheer force they knocked over one of the walls around the square and began to escape into the open fields. The Spaniards then went out into the fields to meet a great force of fully armed warriors, whom they quickly routed and pursued until darkness fell, killing thousands and collecting gold and silver objects in unprecedented quantity. No Spaniard had lost his life.

“Atahuallpa, now a prisoner, promised to fill a room with gold and silver in return for his life, and, as most say, for his liberty as well. The Spaniards agreed. As for Atahuallpa's liberty, it is hard to see how they can have been serious, unless, as Juan Ruiz states, they intended to send him to his homeland of Quito, for the whole expedition was predicated on the assumption of permanent Spanish rule in Peru under Governor Pizarro. The conquerors now settled down at Cajamarca to await the assembly of the treasure and also the arrival of further reinforcements. The country appeared calm, but many of the emperor's "captains" in other areas seemed disposed to assert their independence.

Hernando Pizarro Goes to Pachacámac:

“As the months stretched on, through the spring of 1533, the Spaniards grew impatient and insecure, and began to take a more active part in the treasure collection. In one of the most famous exploits of the whole campaign, Hernando Pizarro took a small body of horsemen and footmen far across the country to the great temple of Pachacámac, near the future site of Lima. Though the gold there proved far less than expected, the Spaniards cast down the idol, and on their way back intercepted a great fortune in the hands of an Inca captain at Jauja.

Emissaries to Cuzco:

“In the same period, three Spaniards were sent under safe conduct to Cuzco, the Inca capital, partly to take possession for Spain, but mainly to hasten the removal of treasure. More successful than Hernando Pizarro, they brought back hundreds of loads of gold, and their feat became legendary, though often attributed to the wrong men.

Distribution of the Treasure:

“Over these months pressures continued to build up. The governor wished to get on with the conquest. The royal treasury officials arrived from San Miguel and were unhappy to see so much gold and silver accumulating, without their being able to dispatch the king's fifth to Spain. In April, 1533, a body of some two hundred men arrived from Panama under Almagro, to learn that they would not receive a share of the growing hoard. They could not complain overmuch of this on principle, but became rapidly disaffected as began to appear that the whole vast wealth of the country would go to the captors of Atahuallpa while they would not receive a penny. On top of all this, reports and rumors began to be heard about large-scale movements of Indian warriors through the countryside; whether true or not, they disturbed the conquerors considerably.

“Thus the interests of almost all the Spaniards were converging on the necessity of eliminating Atahuallpa and distributing the treasure quickly. Assaying and melting down of the metals began in mid-May, in anticipation of Atahuallpa's execution. This then took place in the latter part of July, at about the same time as the distribution of the treasure. The total gold and silver, spoils and ransom together, turned out to be worth over 1.5 million pesos, beyond anything seen or dreamed of in the Indies to that date. All but the king's fifth went to the more than 160 men of Cajamarca… Even lowly footmen now had fortunes exceeding what captains had been able to get in Mexico, Guatemala, or Nicaragua. Some twenty lucky men were permitted to return home with their wealth. The impact of their arrival in Spain was without parallel, particularly on the crown, which soon sent chief emissary Hernando Pizarro back to Peru for more of the same.

Jauja:

“The rest of the Spaniards, both men of Cajamarca and new arrivals, continued the conquest, for so they considered it. Only later would the idea arise that the Inca empire had collapsed with one thunderbolt. The conquerors advanced in formation, expecting resistance and often meeting it, apparently most often from Quito compatriots of Atahuallpa, who were still in central Peru after the Incan civil wars. Leaving Cajamarca in August, 1533, the Spaniards reached Jauja in the central highlands in just two months. There was discussion of making the town their capital, and a Spanish municipality and council were formed, though only provisionally.

Vilcaconga:

“In late October the expedition departed for Cuzco, leaving the royal treasurer, Riquelme, with a substantial party, to hold Jauja and guard the treasure left there. Soto started out several days in advance of the main body with a mounted vanguard. About a week into November, well over halfway to the Inca capital, Soto and his men experienced the worst military disaster of the Peruvian conquest. Trying to get to Cuzco and its riches first, Soto's party had gone too far ahead of the rest and, even worse, had tired out both men and horses. As they were ascending a long slope at Vilcaconga, Indians attacked them with a hail of stones and weapons from above. They barely managed to reach the top, with more casualties than the expedition had suffered in all the rest of the action since Túmbez. A relief party under Almagro extricated them.

Cuzco:

“The Spaniards entered Cuzco on November 15, 1533, and after some skirmishes with the Indians from Quito were well enough received by the rest of the population. During the months that the conquerors quartered in the Inca palaces and other buildings in the center of the city, another great treasure was collected, this time with more silver than gold, and distribution to the men duly took place in early March, 1534. On March 23, 1534, the governor founded a Spanish municipality in Cuzco. Some eighty conquerors enrolled as citizens and received encomiendas in the district, but only forty stayed to guard the town, while all the others returned in the direction of Jauja. The expedition as a band of men was dispersing, and the conquest proper was over.”(Lockhart, The Men of Cajamarca).

JCB (Bibliotheca Americana) I, p,119; Church, Catalogue of books relating to the discovery and early history of North and South America, 73; Alden & Landis, European Americana, 535/21; Harrisse, Bibliotheca Americana Vetustissima, 200; Huth 8219; Medina, Biblioteca hispano-americana (1493-1810), 95 note; Sabin, Dictionary of books relating to America from its discovery to the present time, 105721; EDIT16, CNCE 32877