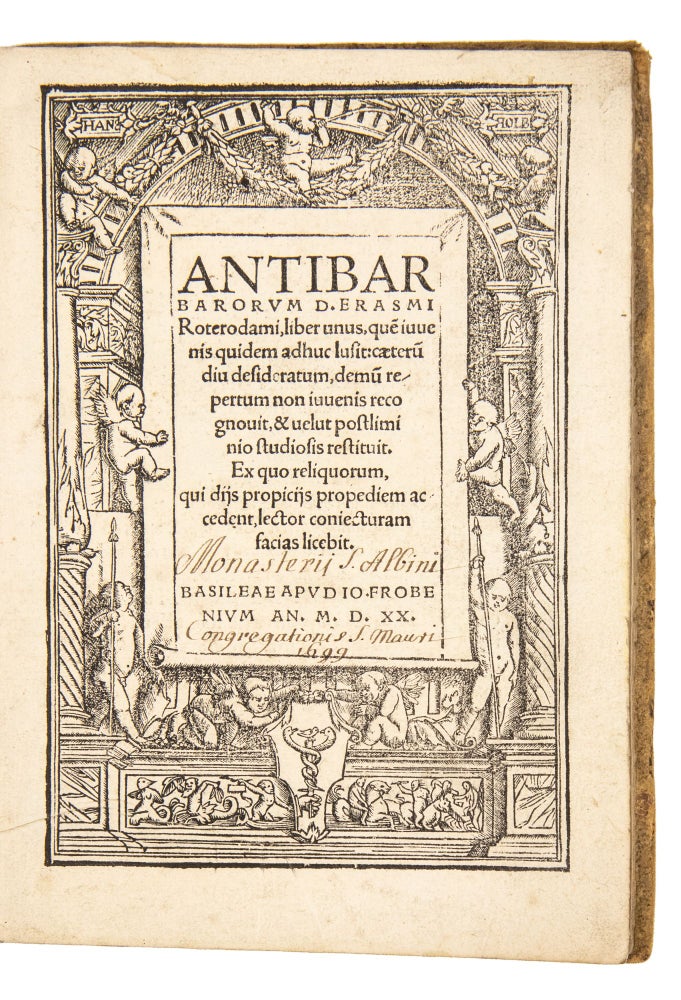

Antibarbarorum D. Erasmi Roterodami, liber unus, quem iuuenis quidem adhuc lusit: caeterum diu desideratum, demum repertum non iuuenis recognouit, & uelut postliminio studiosis restituit. Ex quo reliquorum, qui diis propiciis propediem accedent, lector coniecturam facias licebit.

Basel: Apud Ioan. Froben. Mense Xbri. 1520.

Price: $12,000.00

Quarto: 20.5 x 15.4 cm. 147, [1] p. Collation: A-R4, S6

SECOND FROBEN EDITION (1st ed. May 1520).

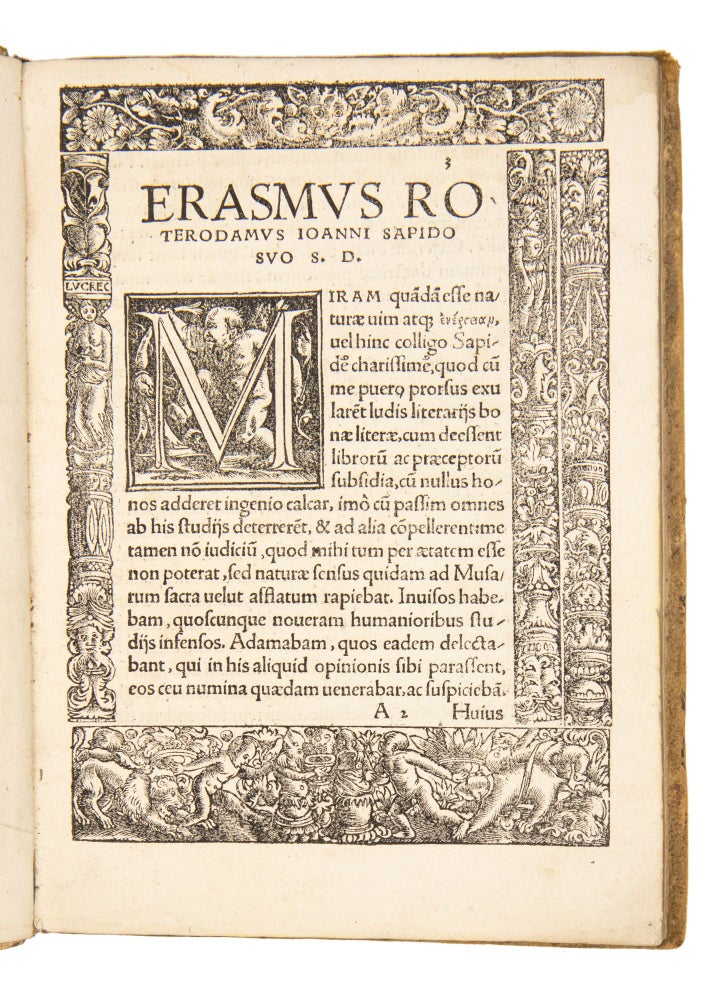

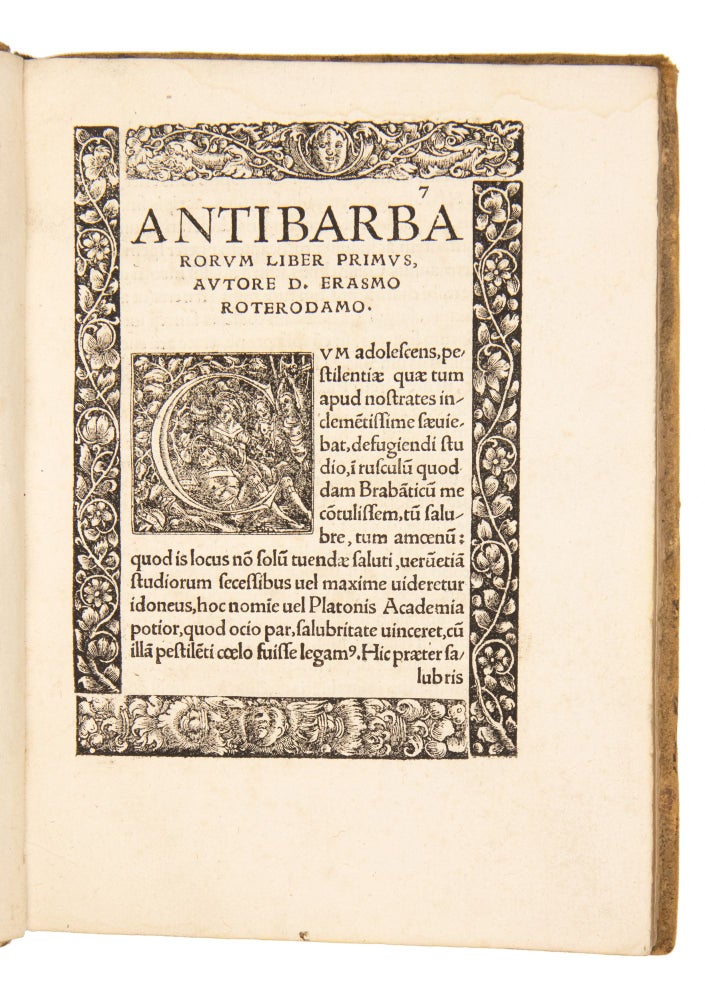

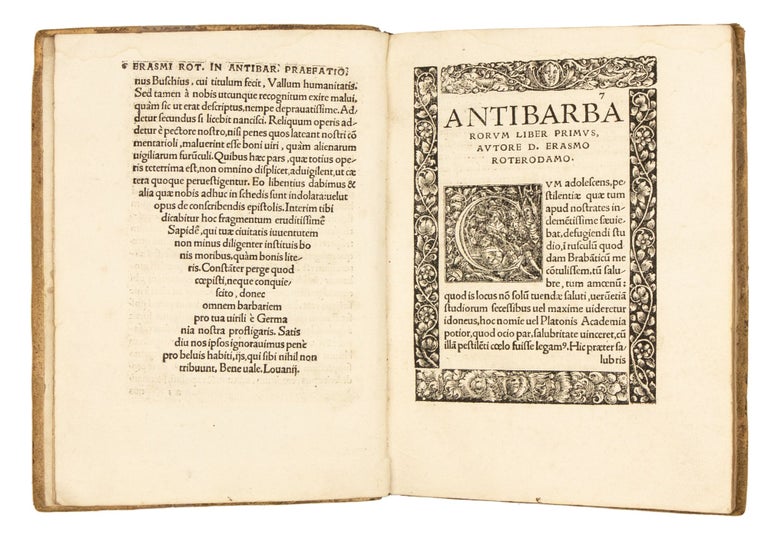

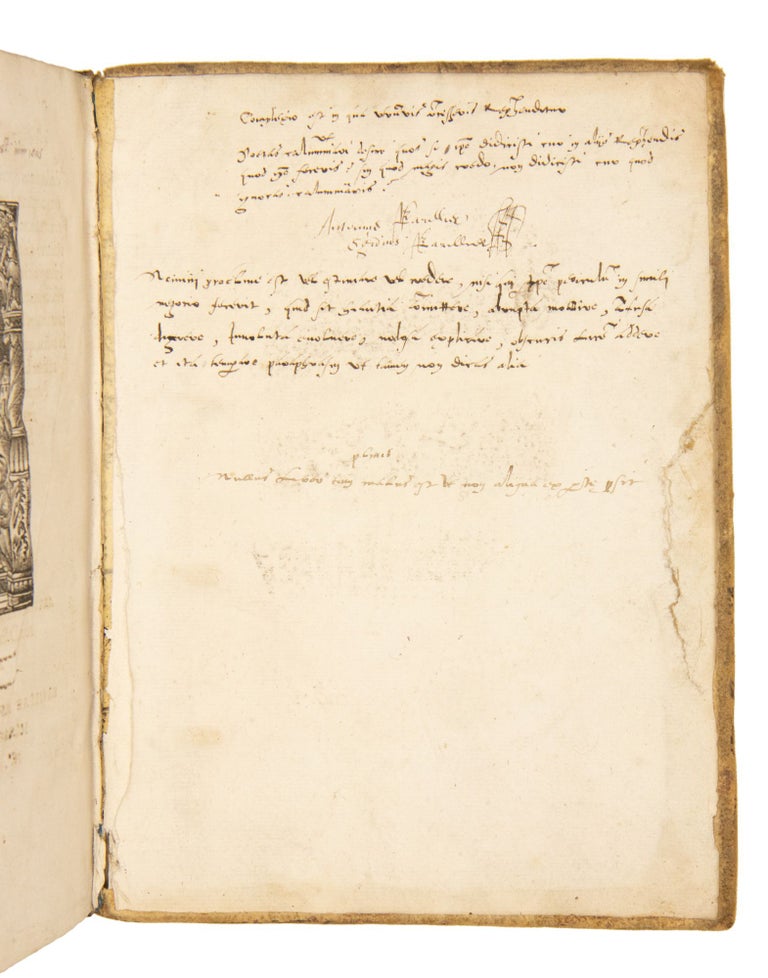

Bound in contemporary reversed-deerskin (with minor stains and surface wear). A fine, tall, and fresh copy. Woodcut border by Hans Holbein to title page, additional woodcut borders to second leaf and the opening leaf of the text. Woodcut Froben device on verso of final leaf. Neat contemporary annotations in the margins, a few trivial marginal stains, final leaf with light crease, light soiling to t.p. and final leaf. Provenance: 17th c. inscription on t.p. “Monasterii S. Albani Congregationis S. Mauri 1699.” 16th c. ownership inscription (struck through) on pastedown.

Second Froben edition, printed within 6 months of the first, of a book begun by Erasmus when he was a young humanist monk in his twenties and completed twenty-five years later, by which time he had become a figure of international renown and controversy.

As originally conceived in the 1490s, Erasmus’ “Antibarbarians” was to be a spirited defense of humanism, in particular the reading and study of classical literature and languages, against charges that such literature and pursuits are fundamentally un-Christian. In its final form, as published in 1520, the book was also a defense of Erasmus’ theological positions, his views on church reform, and his application of humanist principles and philological methods to the study of religious texts, in particular Holy Scripture.

Erasmus conceived his “Antibarbarians” at about the age of twenty, while living as a monk at the monastery at Steyn. By the time the book was published, Erasmus was under attack from many quarters, especially from the monastic orders, whose members resented Erasmus’ criticisms of their abuses and accused Erasmus of heresy and Lutheranism.

The threat to humanistic studies that Erasmus had perceived in the 1490s was still alive and well but had taken on new dimensions and implications. The Louvain theological faculty had condemned Erasmus’ Greek New Testament, the preeminent expression of Erasmian humanism, and had also attacked Erasmus for his part in the so-called Reuchlin affair, “long regarded as the first formal confrontation of the new scripture-based reform with the scholastic defenders of the theological faculties and the Vulgate.”(Levy, p. 177)

Forced to defend himself on these fronts and to clarify his positions, Erasmus used the “Antibarbarians” as a vehicle to stage his defense and to launch new attacks on his enemies.

The Genesis and Development of the Work:

“Erasmus arrived in Paris in 1495 and soon after his arrival submitted the first book of his ‘Antibarbari’ to the historian Robert Gaguin. In 1499 Erasmus went to England and it was probably then that he showed the drafts of Books I and II to John Colet. During the penurious years in Paris that followed, he apparently went on with it during the time he could spare from his teaching. He took it with him to Italy in 1506, and revised Books I and II at Bologna. But when in 1509 he received an urgent invitation to come to England and share in the golden age that was opening with the reign of Henry VIII, he left Italy in a hurry and consigned his papers to the care of an English friend, Richard Pace, at Ferrara. Soon Pace had to leave too and the papers went to another Englishman, less conscientious, who sold what he could and gave the rest away.

“Erasmus asked over and over again for the return of his brainchild. But he never saw most of it again. He got hold of Book I when he was in Louvain many years later, revised it again, and sent it to Froben, who published it in 1520. The reason given for this was that Erasmus had found the manuscript circulating from hand to hand, and he was conscious of its juvenile mistakes; the only way to deal with this was to produce a new and revised edition. A year or two later he had the beginning of Book II sent from England and found the end of the same book at Bruges. But nothing more ever emerged, and he never fulfilled his intention of rewriting it.”(Margaret Mann Phillips, ‘The Antibarbarians’, in The Collected Works of Erasmus, Toronto, Volume 23)

The Printed Version:

“The work is a spirited defense of the study of the classics, in the form of a dialogue between Erasmus and his friends: William Hermans, a monk like himself from the monastery at Steyn; an energetic character named Jacob Batt, town clerk of Bergen; the burgomaster of Bergen, Willem Conrad; and the town doctor Jodocus. They meet and talk, and their conversation develops into a debate on the reasons for the stiff resistance they find among the traditionalists to the introduction of classical studies.

“Three of the interlocutors are young enthusiasts, considered by the older generation as revolutionary and subversive because they want to substitute the ‘abominable monsters of paganism’ (Horace, Vergil, and Ovid) for the accepted reading of the schools. The two others are in agreement with the younger men, and together they discuss the motives for this resistance and for the decline of true learning.

“The doctor says it is because of the stars (he is addicted to astrology); the burgomaster says it is because of Christianity; Willem Hermans says it is the result of the ageing of the world. Batt, however, puts it all down to the terrible teachers who reign undisputed in the field of education. The others beg him to make this clear, and he explains himself in a long speech, punctuated by a few remarks from his hearers. He sketches the battlefield, divides the enemy into three camps –the ignorant, the narrow-minded, and those who wish to use learning for their own ends- and starts an eloquent attack on the first group, who know nothing about the classics and therefore regard them as harmful (‘Beware, he’s a poet, he’s no Christian!’) or who take their stand on apostolic simplicity.

“Eventually the burgomaster’s wife sends a servant from their country house nearby to say that dinner is spoiling, and they decide to adjourn and take up the discussion in the afternoon. That afternoon, for us, has not arrived. The stage being set, Erasmus intended to develop the theme in three more books. After the refutation of the enemies of humanism, the second book was to provide an answer to this, in which a fictitious character used all the powers of eloquence to pour scorn on eloquence; the third book was to be a refutation of the second, and the fourth a defense of poetry.

Bibl. Erasmiana I, 9, Bibl. Erasmiana II, 72, Bibl. Belgica E 289, VD16 E 1998