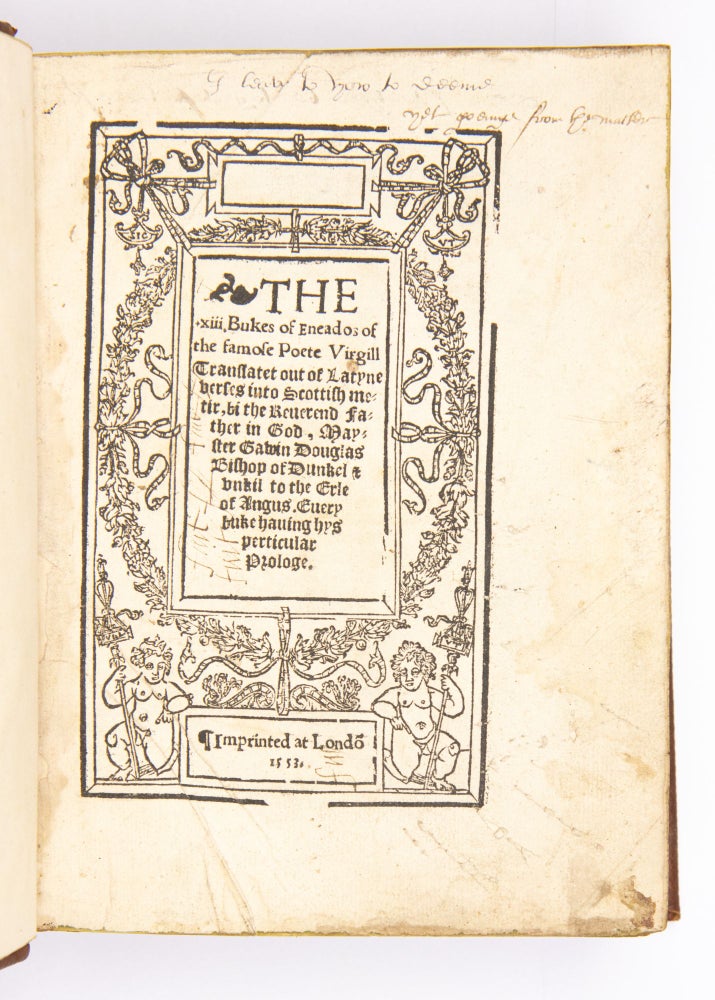

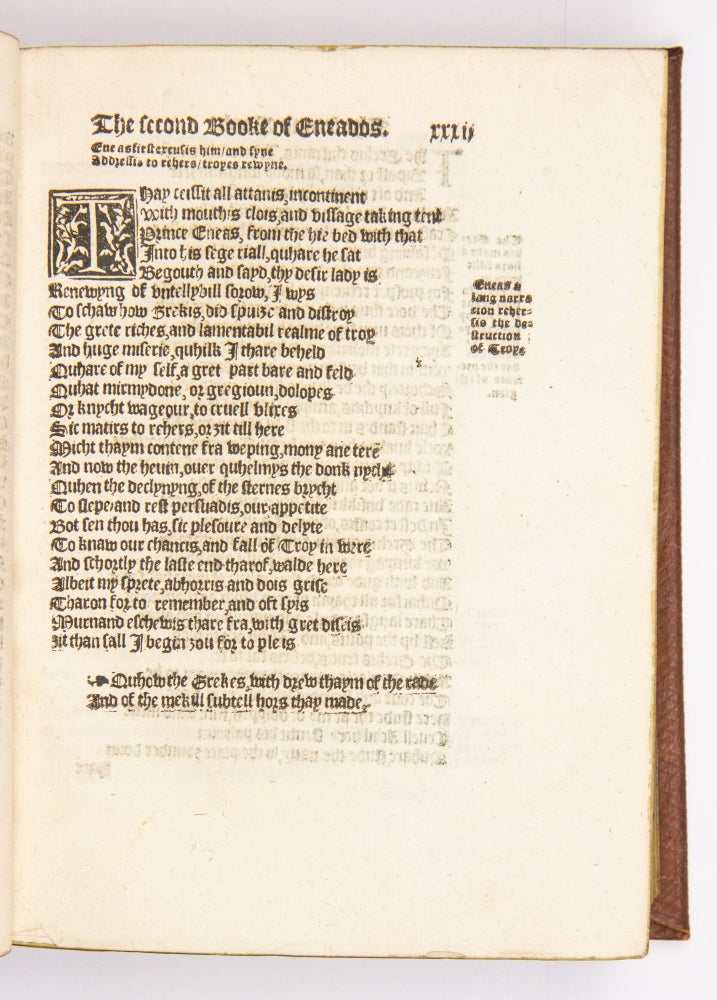

The xiii. Bukes of Eneados of the Famose Poete Virgill Translatet out of Latyne verses into Scottish metir.

London: William Copland, 1553.

Price: $75,000.00

Quarto: 22 x 16.5 cm. A1, B-V8, X8+1, Y-Z8, a-z8, aa-bb8 (-bb8 blank)

FIRST EDITION.

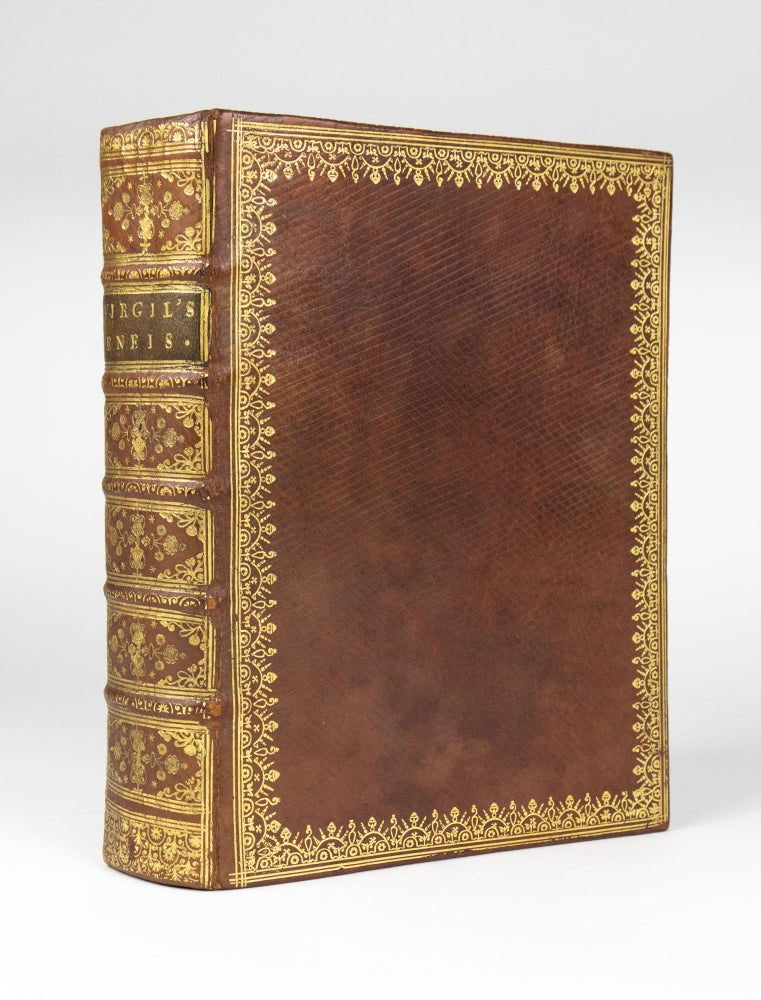

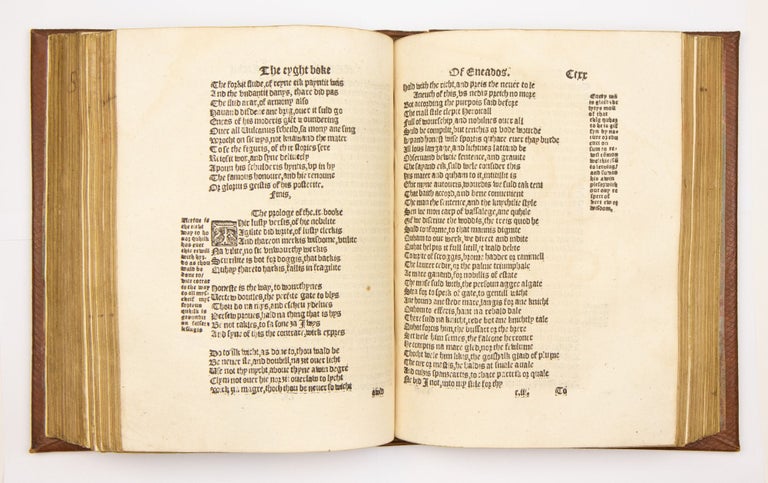

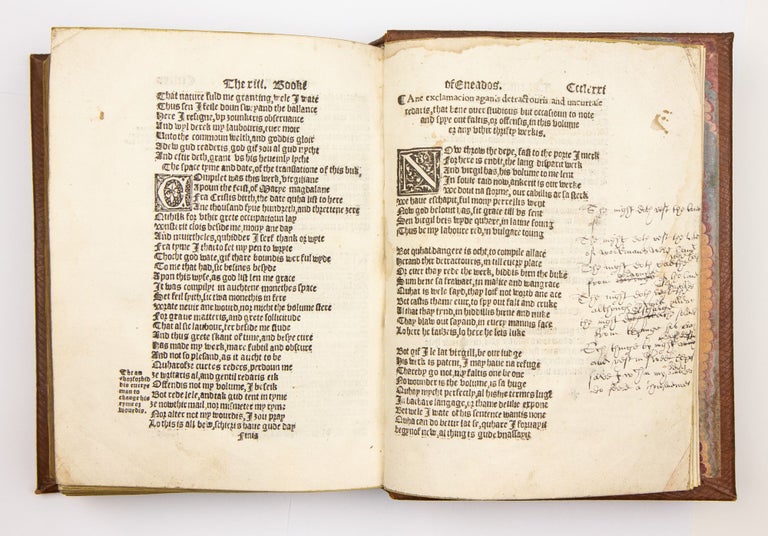

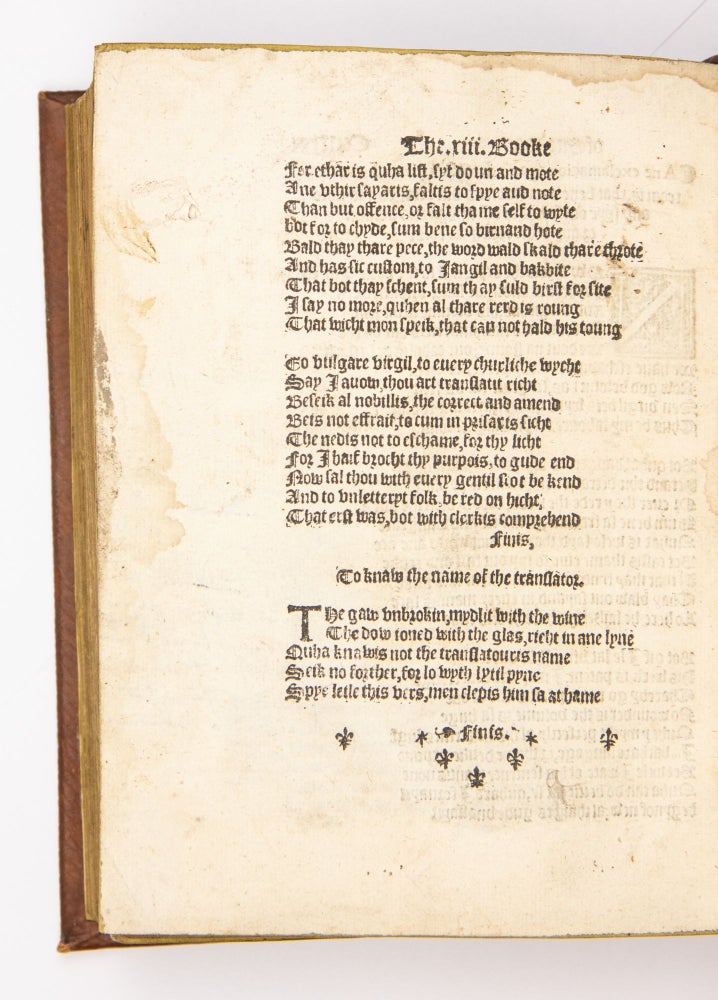

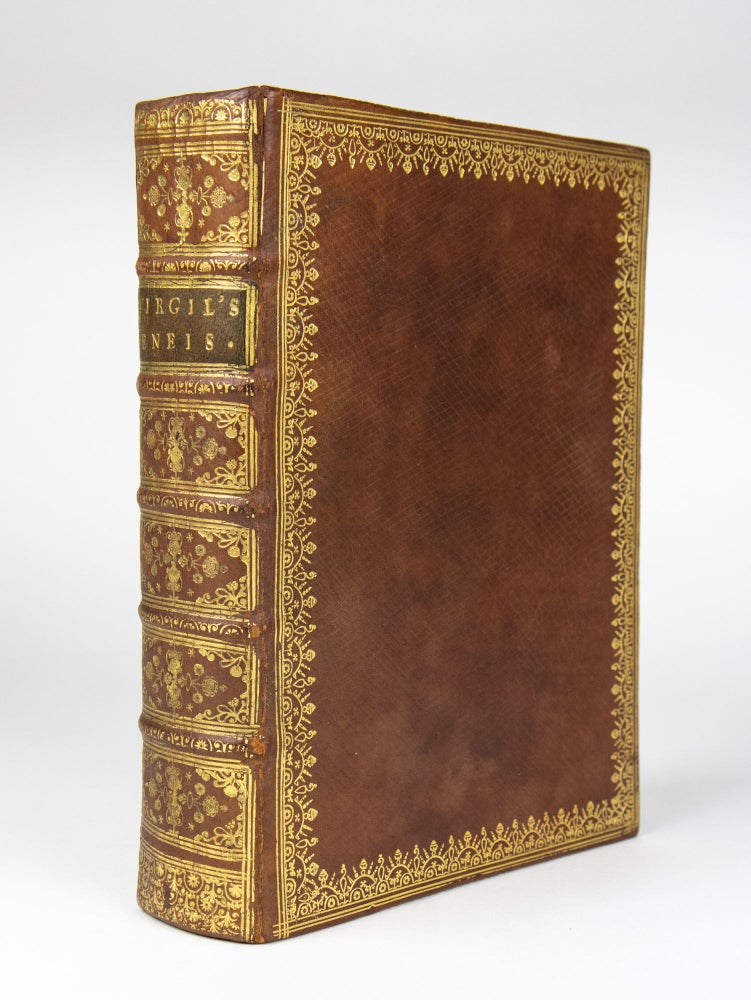

Bound in 18th century diced russia, boards and spine ornately tooled in gold, housed in a modern full dark blue morocco folding case by Sangorski & Sutcliffe. Title page printed with an elaborate woodcut compartment (McKerrow & Ferguson 49a), text in black letter, with the inserted leaf in signature X and the leaf with "Ane exclamacion against detractouris" (Bb7) present; lacking the final blank; small hole in i8 and t4, each with a slight loss of text; blank corners torn from M8 and g1; outer margin of the title slightly stained and the inner margin with some holes (abrasions), lli-2 with minor ink stains; some marginal damp-stains at end; marginal notes to title; S7-8 spotting in margins; C5 with small tears in outer margin; final leaf with small marginal holes. All defects listed are slight, overall a very pleasing copy. Ex libris Sir Thomas Phillipps, sold at auction 26 November 1974; sold again as part of the collection of the Garden Ltd., in 1989.

On the final leaf is an unrecorded 12-line poem in Scots by an anonymous poet that begins "The night doth rest the toyle/ of workmans were hand” and ends “Save I w[hi]ch in my bedde [slumber]/ do feele a thousand waes.”

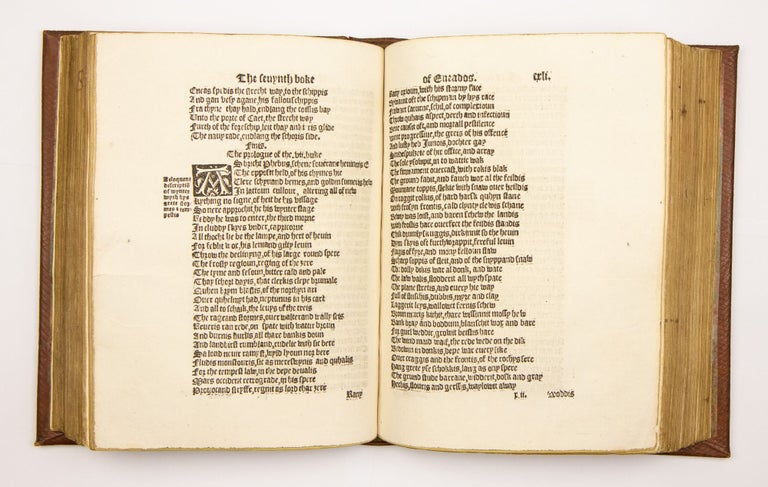

According to Pforzheimer “by an oversight of the printer some lines at the end of the prologue and beginning of the text of the seventh book were omitted necessitating the insertion of the extra leaf in quire X [chi1]. This leaf . . . is . . . much more common than is the leaf Sig [bb7] containing ‘Ane exclamacion agains detractouris’ and the anagram on the translator’s name.” Our copy contains both chi1 and bb7.

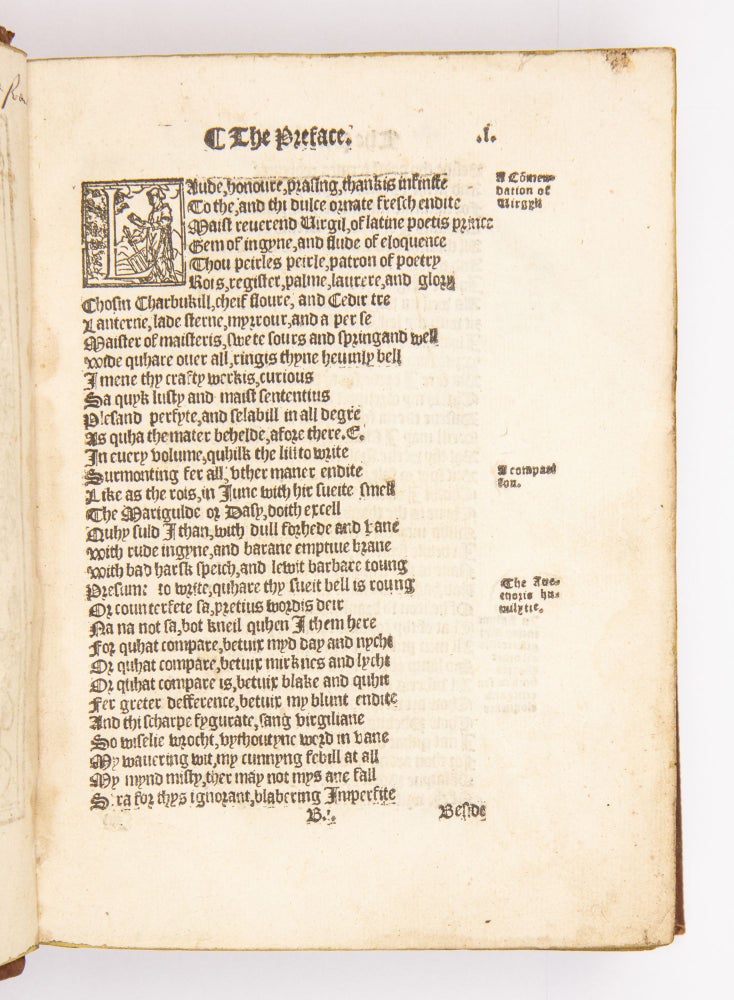

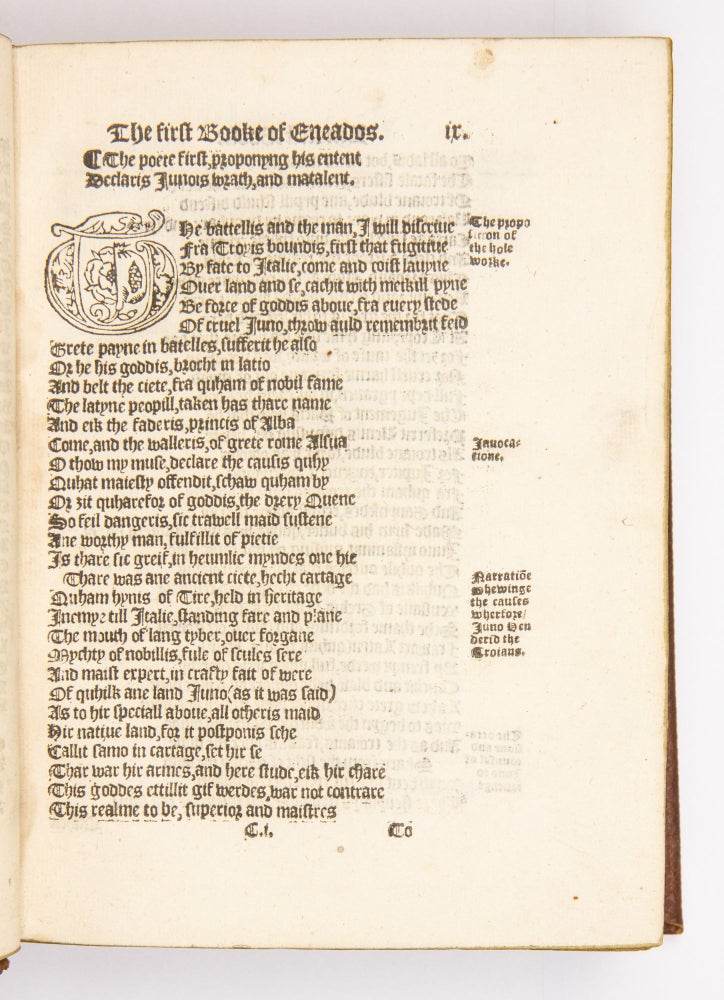

Gawin Douglas’ Middle Scots (not to be confused with Gaelic) translation of Virgil's “Aeneid” is the first translation into any Anglic language (Caxton’s 1490 prose epitome “Enydos”, which Douglas criticizes in his preface, was merely a free adaptation of the poem from a French rendering).

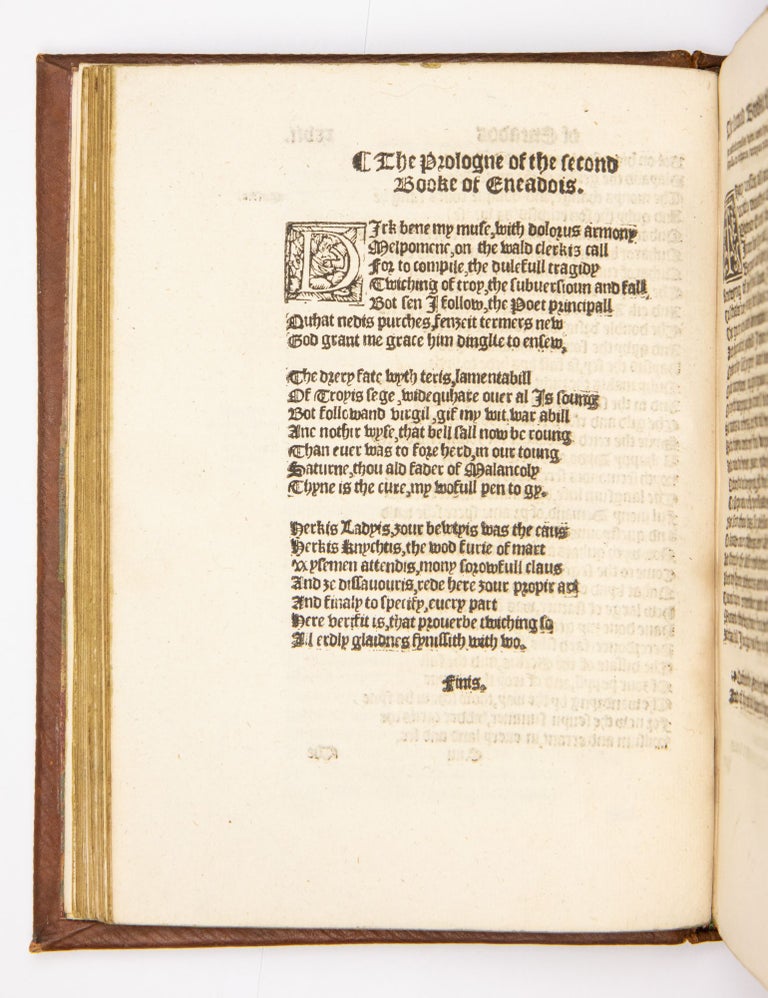

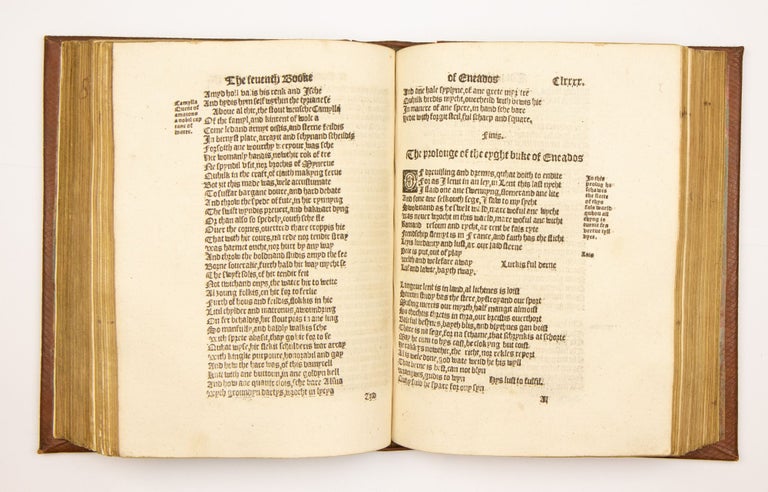

Douglas also included his translation of Maffeo Vegio’s (1407-1458) thirteenth book, which brings Virgil’s poem to an end with the funeral of Turnus, and added his own original verse prologues to each book. Douglas’ translation, completed on 22 July 1513, remained in manuscript until the appearance of this, the first and sole 16th century edition, in 1553. There are several early MSS. of Douglas’ “Aeneid” extant: (a) in the library of Trinity College, Cambridge, c. 1525, (b) the Elphynstoun MS. in the library of the university of Edinburgh, c. 1525, (c) the Ruthven MS. in the same collection, c. 1535, (d) in the library of Lambeth Palace, 1545-1546.

Gawin Douglas (ca. 1474-1522), the last of the great Chaucerians, was the son of the fifth earl of Angus. He became a priest at a young age and rose -although not without bitter rivalry- to be archbishop of Dunkeld in his native Scotland. He served Queen Margaret who had married Douglas’ nephew (the sixth earl of Angus) after her husband was killed at Flodden Field. Douglas died at London in 1522 of the plague. He was an accomplished poet. In addition to his ‘Eneados’ and the poems of the prologues, he is remembered for two allegorical verse narratives “The Palice of Honour” and “King Hart” describing respectively the ascent to virtue and to illumination.

“In the early 1500s no major classical work had been translated into English, and Douglas's ‘Eneados’ was a pioneering work; what is more, it was not a free paraphrase nor a mere sample of one or two books, but a careful translation of the whole of Virgil's great poem. Douglas was aware of the novelty of his undertaking. He proudly asserted his own fidelity to Virgil's text, and voiced pungent criticisms of William Caxton's recent version of the ‘Aeneid’, which was no more like Virgil 'than the devill and Sanct Austyne' (prologue 1, 143)… The ‘Eneados’ was affectionately dedicated to Henry, Lord Sinclair, whom Douglas characterized as a keen bibliophile and 'fader of bukis' (prologue 1, 85). He did not design his translation, however, solely for aristocratic readers, but envisaged a wider audience, including 'masteris of grammar sculys', teaching on their 'benkis and stulys' (Virgil's ‘Aeneid’, 4.189). Douglas shared the values of the humanists: an antipathy to scholasticism, respect for classical authors, and a zeal for education. He wished to communicate to his countrymen a knowledge of the ‘Aeneid’, and also to enrich his native 'Scottis' tongue with something of the 'fouth', or copiousness, of Latin…

“Knowledge of Douglas's critical ideas on a wealth of topics, including Virgil and Chaucer, and the problems of translation, derives largely from the prologues which he furnished for each book of the Eneados, and the series of epilogues, in which he took a leisurely farewell of Virgil, his patron, his readers, and even his critics. The prologues vary greatly in tone, length, and metrical form—this includes rhyme royal, the decasyllabic couplet (used also for the translation), and the archaic 13-line alliterative stanza of prologue 8. Critics have debated the relevance of some of them to the Aeneid, and whether they might better be regarded as independent poems. There is no doubt, however, that they contain much of Douglas's finest and most original writing. Several offer glimpses of the poet in the process of composition; prologue 7 contains a brilliant vignette, in which the poet rises from bed on a wintry morning and shudders at the cold, before he turns to resume work at his lectern. Douglas's tone is often highly colloquial: sometimes he chats familiarly with his readers, sometimes he exhorts them to read poetry attentively—'Considdir it warly, reid oftar than anys [once]' (prologue 1, 107). Prologues 7, 12, and 13, commonly entitled the ‘nature prologues’, are outstanding for their perceptive description of the natural world in winter and summer, moving from tiny and vivid details to grand panoramic vistas.”(Bawcutt, ODNB)

“In his translation of Vergil, Douglas is on quite untrodden ground. He has the merit of being the first classical translator in the language and he seems to have set his own example by working at passages of Ovid, of which no specimen exists. He must have done the whole work, prologues and all, together with the translation of Maffeo Vegio’s ‘Thirteenth Book’, within the short span of eighteen months. He writes in heroic couplets, and his movement is confident, steadfast, and regular. In several of the prologues he reaches his highest level as a poet. He shows a strong and true love for external nature, at a time when such a devotion was not especially fashionable; he displays an easy candor in reference to the opinions of those likely to criticize him; he proves that he can at will (as in the prologue to Book VIII) change his style for the sake of effect; and in accordance with his theme he can be impassioned, reflective, or devout. The hymn to the Creator prefixed to the 10th book and the prologue to the book of Maphaeus Vegius -descriptive of summer and the ‘joyous moneth tyme of June’- are specially remarkable for loftiness of aim and sustained excellence of elaboration.”(DNB).

STC 24797; Pforzheimer 1027; ESTC S119190; Langland to Wither 61