Three works bound together: I. The Shepheards Calender (1591); II. The Faerie Queene (1596); III. Colin Clouts Come Home Againe (1595)

London: Various printers (details below). 1591-, 1596.

Price: $85,000.00

Quarto: 19.4 x 14.5 cm. The works are individually described below.

A remarkable volume containing 3 separately-printed works, including the first editions of the second part (Cantos 4-6) of The Faerie Queene (1596) and Colin Clouts Come Home Againe (1595).

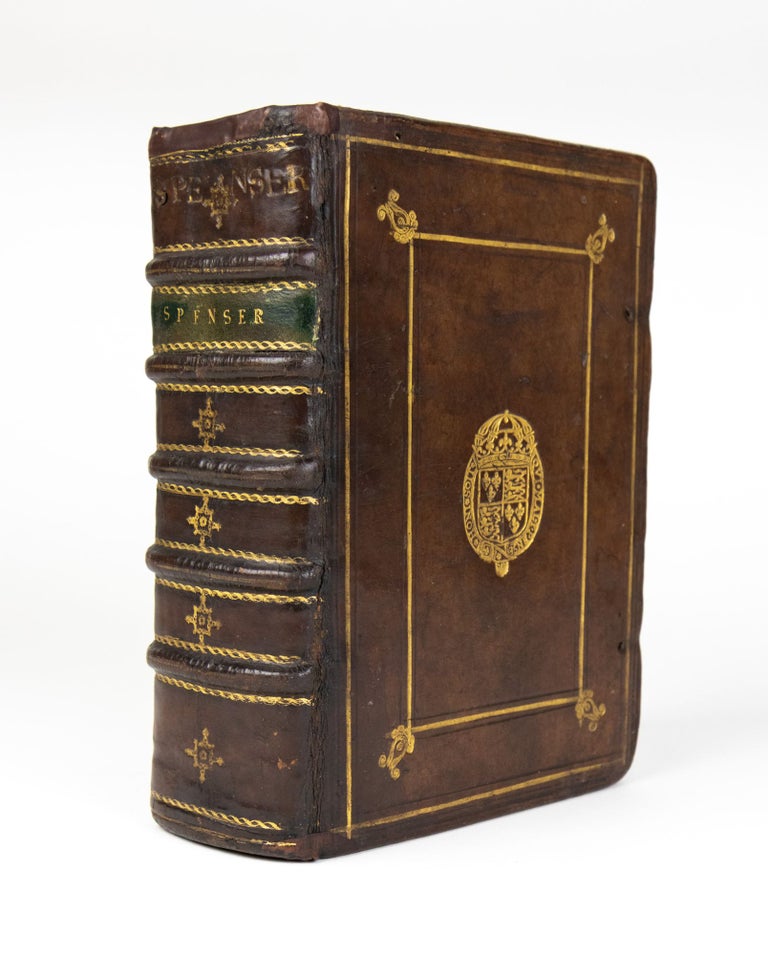

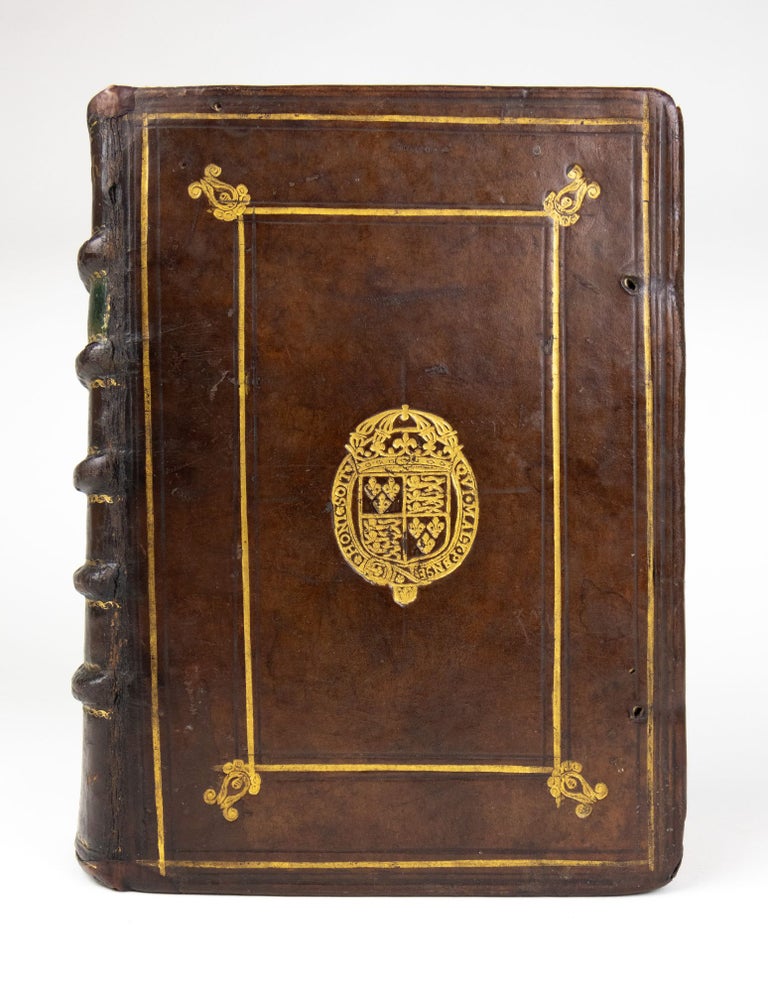

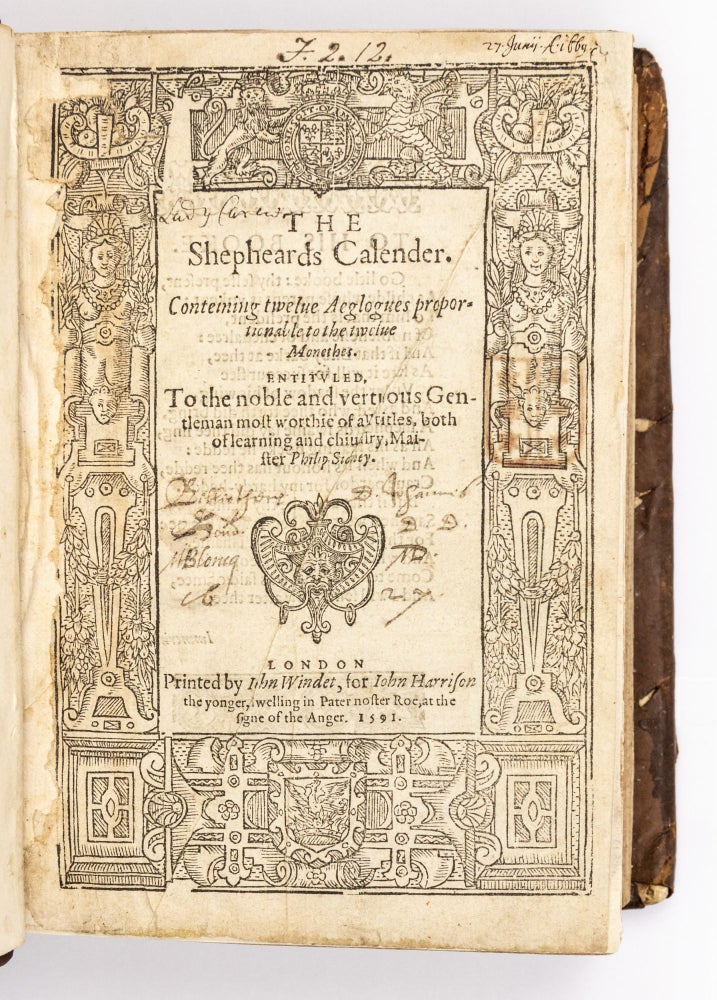

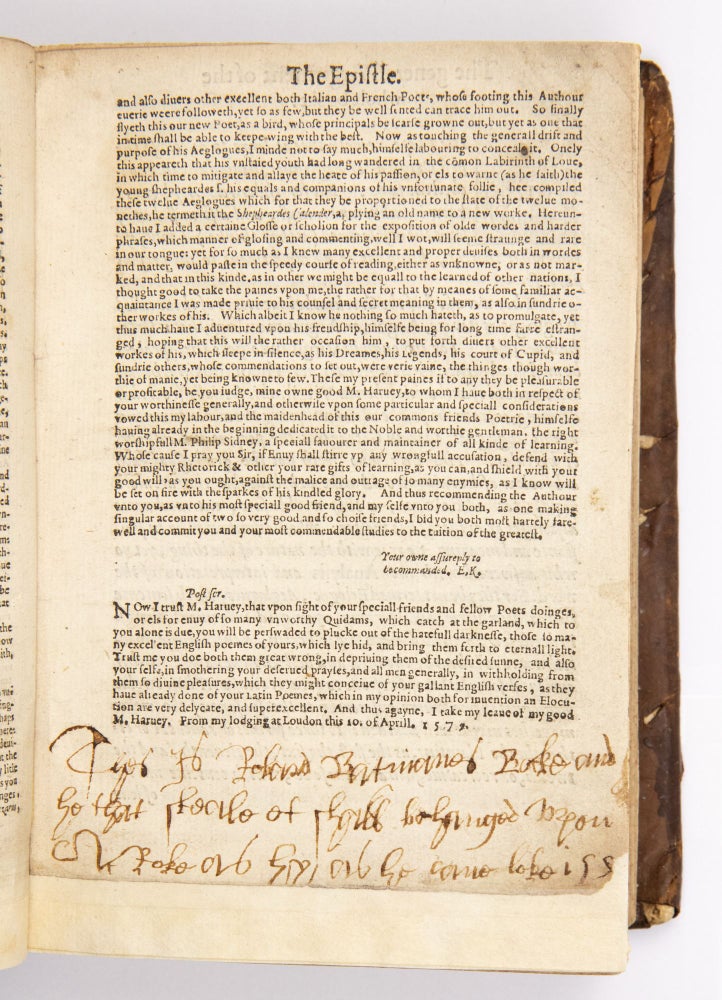

Bound in 17th c. calf, the boards gilt-ruled in compartments with ornamental tools at the corners and a large stamp of the Tudor arms at the center of each board (hinges and endcaps restored, corners bumped, later label, lacking ties). Inscriptions: In the Shepheards Calender 1. Contemporary signature of Roger Collings on p. 1; 2. Inscription in Latin on title page, “To the library of Lord John Bond as a gift by M[onsieur] Bloncq [i.e. Blanc] A.D. 1627”. 3. Also on t.p., “Lady Carew” and “June 27, 1669” (perhaps Mary Morice of Wirrington (d. 1698), Lady Carew). 4. Unidentified armorial stamp on verso of t.p. For condition of contents, see individual entries below. 5. Another -and quite marvelous- contemporary inscription on the third preliminary leaf of the Shepheards Calender: “This is Robard Batmans Booke and he that steale et shall be hanged vpon A Roke as Hy as he cane loke.”.

I. THE SHEPHEARDS CALENDER.

London: Printed by Iohn Windet, for Iohn Harrison the yonger, dwelling in Pater-noster roe, at the signe of the Anger, 1591.

Quarto: [4], 52 lvs. Collation: *4, A-N4 (3 preliminary leaves supplied and genuine).

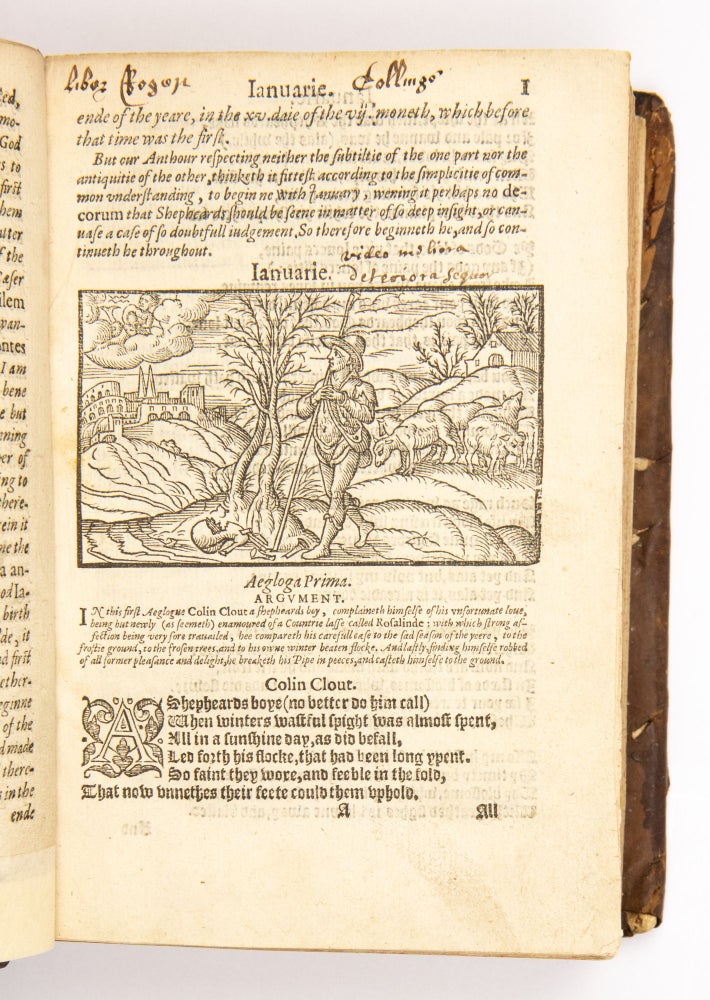

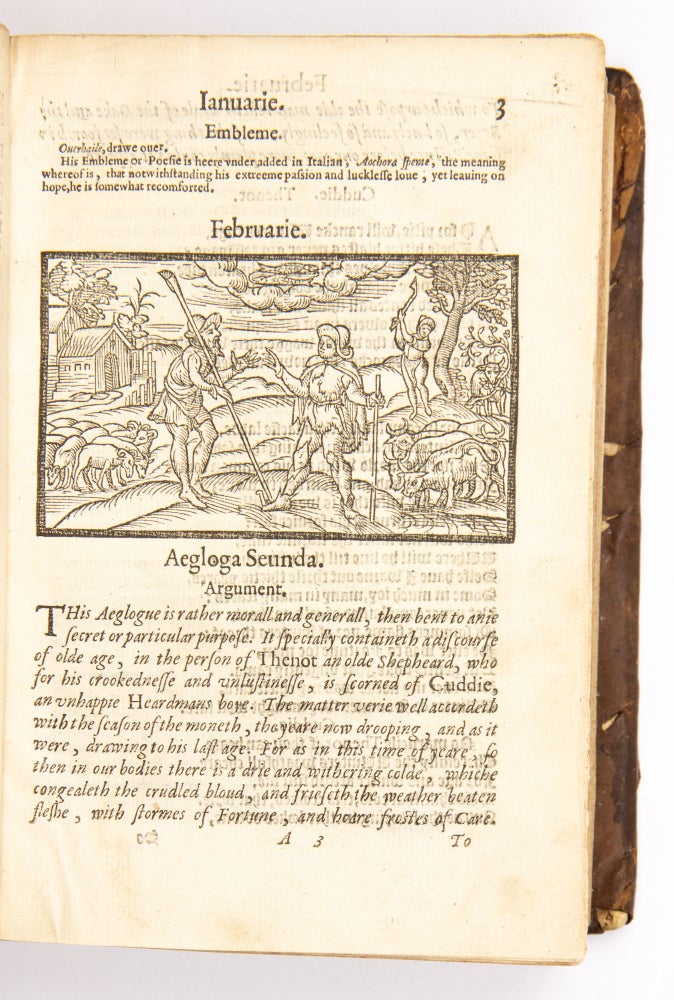

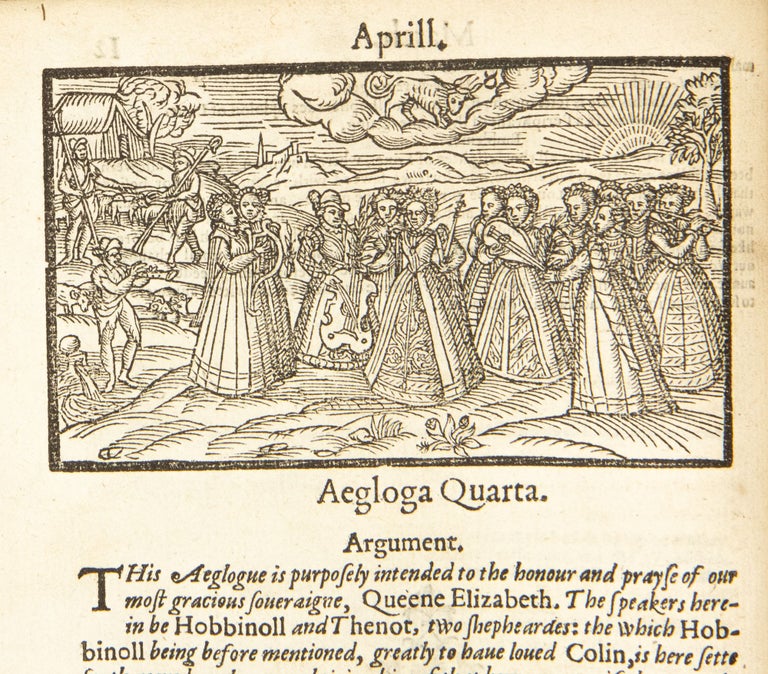

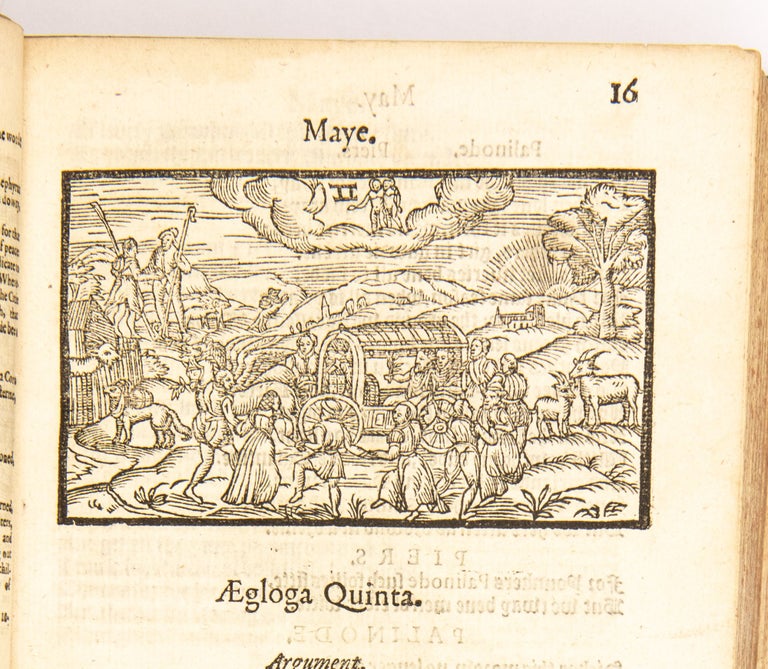

FOURTH EDITION. (1st ed. pub. 1579). Title within woodcut border (McKerrow & Ferguson 198). The text is illustrated with 12 woodcut vignettes, one for each month. Restorations to inner margin of title with some loss to the lefthand portion of the woodcut border, small repair to upper, outer corner (no loss), 3 preliminary leaves following title supplied from a shorter copy (blank lower margin restored.)

The woodcut for April shows Queen Elizabeth and her entourage.

“This and the edition of 1586 are counterparts of each other… The illustrations are printed from the same blocks; the type, however, was reset, there being slight differences in spelling, etc., and the printer’s ornaments at the foot of the eclogues are different.” (Langland to Wither, No. 229, p. 199-200)

“Published in 1579, a decade before ‘The Faerie Queene’, this book of pastorals established Spenser as the leading poet of his generation. Its editor, one "E.K." (never identified but clearly someone associated with Spenser), heralded the work as a major literary event and its author as ‘our new poet.’ It was reprinted four times in Spenser's lifetime and evoked imitations and admiring comments almost from the date of its publication. Spenserians and traditional literary historians still take ‘The Shepheardes Calender’ at E.K.'s valuation and treat it (not without reason) as inaugurating the great age of Elizabethan poetry… It was the first set of English pastorals in the European tradition, and in emulating Virgil's Eclogues, it self-consciously inaugurated a poetic career on the model of Virgil's-one that would move from a book of eclogues to a national epic.”(Alpers, Pastoral and the Domain of Lyric in Spenser's Shepheardes Calender)

“’The Shepheardes Calender’ was entered into the Stationers' register on 5 December 1579 and was published by the protestant publisher Hugh Singleton soon after that date, as the poem bears the imprint 1579 (indicating that it must have appeared before the end of February). The ‘Calender’ was a popular work and was reprinted in 1581, 1586, 1591, and 1597, demonstrating that Spenser did make an impact as 'our new poet'. It contains twelve poems, complete with prefatory comments and notes by E. K., which may or may not have been written by Spenser himself and Gabriel Harvey, and a series of emblematic woodcuts of allegorical significance. The poems describe events in the lives of a series of fictional shepherds and vary from apparently personal laments on the nature of loss and unrequited love to stringent ecclesiastical satire and attacks on corruption and court patronage. They comment on the nature of love and devotion, the pains of exile, praise for the queen, forms of worship, the duties of church ministers, forms of poetry, the merits of protestantism and Catholicism, and impending death. Equally important is the showy technical proficiency of the works and the ways in which the poems and commentary serve to announce the arrival of a major new English poet.”(Hadfield, Oxford DNB)

ESTC S111267; STC 23092; Langland to Wither 229; Johnson, Edmund Spenser, 4; Luborsky & Ingram. Engl. illustrated books, 1536-1603, 23092

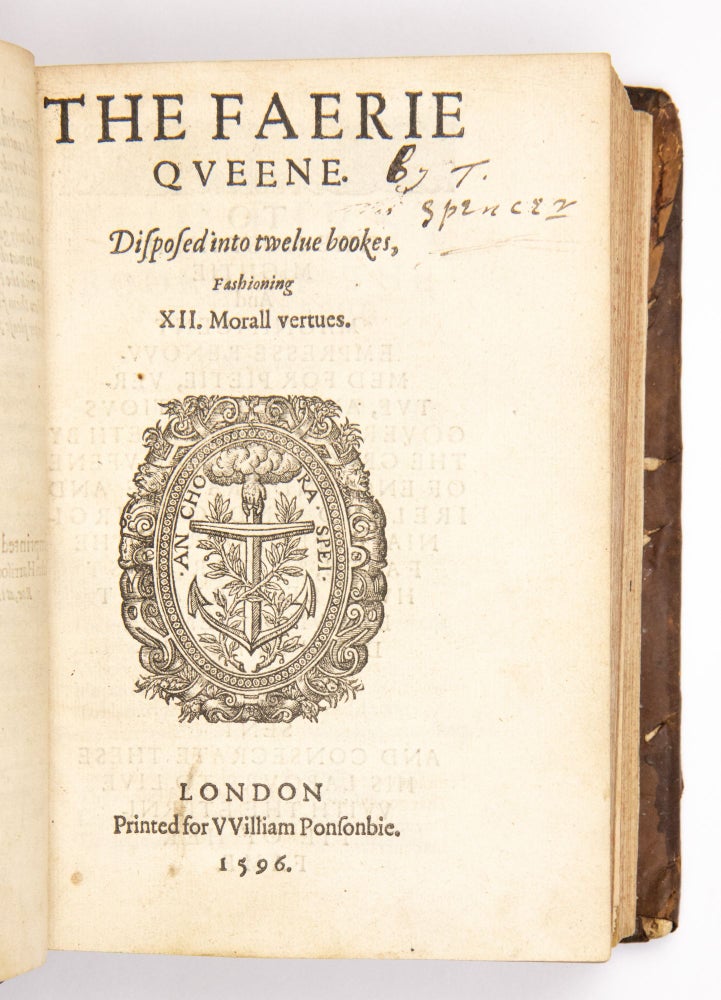

II. THE FAERIE QUEENE Disposed into twelue bookes, fashioning XII. morall vertues

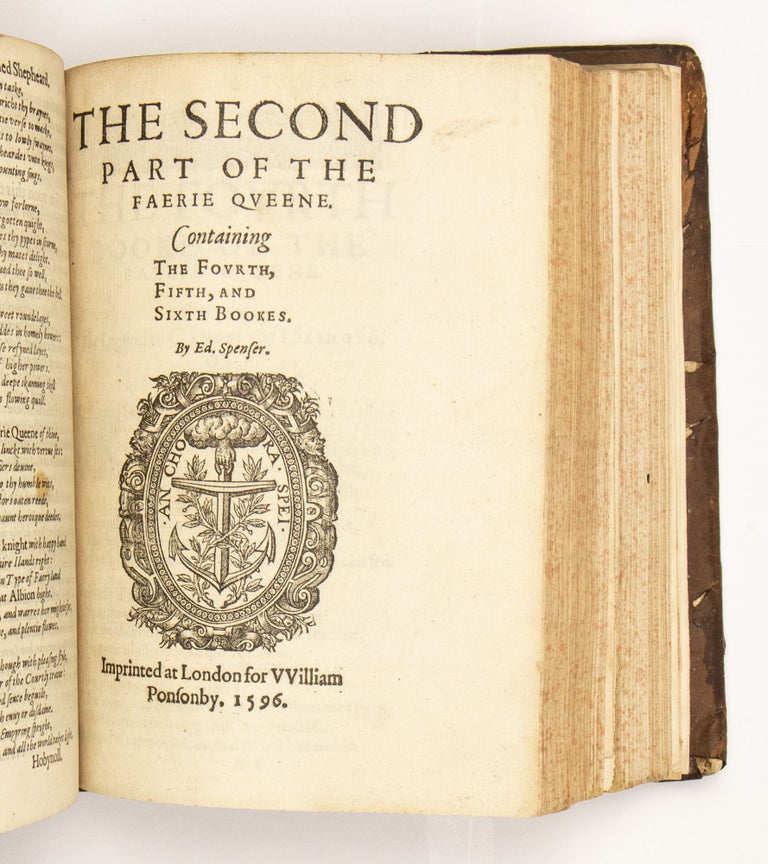

[First and Second Parts].

London: Printed [by Richard Field] for William Ponsonbie, 1596

Quarto: [2], 590; 518 p. Collation: Part 1: A-Z8, Aa-Oo8; Part 2: A-Z8 (signature Z supplied from another smaller copy), Aa-Ii8, Kk4.

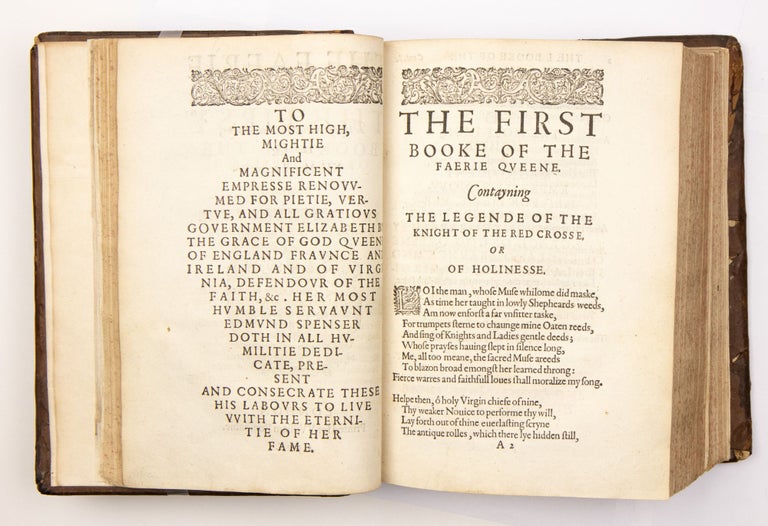

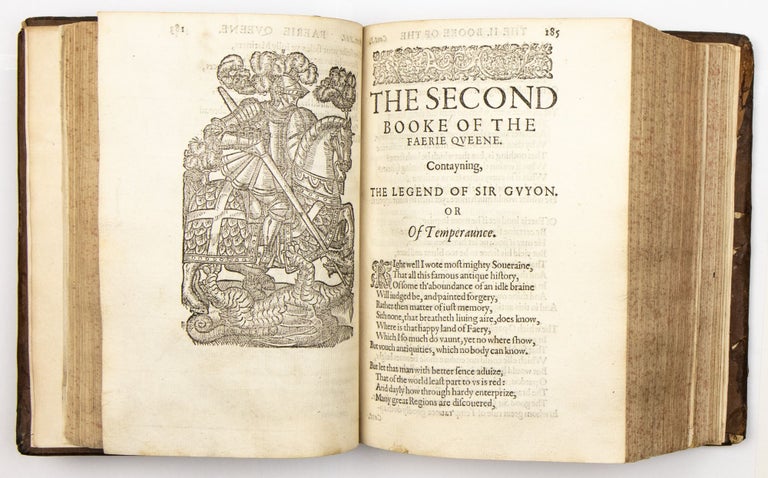

SECOND EDITION OF THE FIRST PART (1st ed. pub. 1590), FIRST EDITION OF THE SECOND PART. With a full-page woodcut at the beginning of book two (p. 184) depicting the Red Cross Knight slaying the dragon. Ornamental metal-cut cartouches frame the argument at the opening of each canto. Light dampstain to lower margin of scattered gatherings in second part, a bit stronger in gathering Cc. The supplied gathering (Z) is shorter and lightly damp-stained and yellowed. Short worm-trail in lower margin of Dd-Ff in second part, not intruding on the text. A few small rust marks.

“’The Faerie Queene’ was a new departure in the history of English poetry, being a combination of Italian romance, classical epic, and native English styles, principally derived from Chaucer. Spenser signalled this by inventing a new stanza (which has come to be known as the Spenserian stanza), a hybrid form adopted from the Scots poetry of James I, ‘rhyme royal’, and Italian ‘ottava rima’. It contained nine lines, the first eight being pentameters and the last line an alexandrine, and employed the rhyme scheme ababbcbcc. It was accompanied by seventeen dedicatory sonnets to a variety of figures… addressed to a range of important courtiers [among them]: Sir Christopher Hatton; Robert Devereux, second earl of Essex; Sir William Cecil, Lord Burghley; Edward de Vere, seventeenth earl of Oxford; Sir Francis Walsingham; Sir Walter Ralegh; Mary Sidney, countess of Pembroke; Lady Carew; and 'all the gratious and beautifull Ladies of the Court'…

“The poem has survived as a long fragment of six completed books, each of twelve cantos, of lengths varying from forty to eighty stanzas. A further fragment of a seventh book, published after Spenser's death, consisted of two complete cantos and two stanzas from a third. There was also a letter appended from the author to Ralegh, dated 23 January 1589, explaining the allegorical method of the 'Poet historical'. Scholars are divided on the question of the extant nature of the poem, some concluding that Spenser never really intended to complete it, others that had he lived longer all twelve books would have emerged…

“’The Faerie Queene’ tells a series of discrete but interrelated stories based around the quests of six knights who each represent a particular virtue. Its allegory is flexible and moves easily from the historically specific to deal with theological, philosophical, and ethical questions, many based on readings of Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics, a stated source of the poem. Book 1 tells the story of the redcross knight, eventually revealed to be the patron saint of England, St George, who has to destroy the dragon who holds captive the parents of his lady, Una. As with all romances the narrative moves sideways as much as forwards (a process known as dilation), and a whole series of episodes represent events and problems precipitated by the Reformation. The lovers are united but, significantly, the knight is recalled to his service to Gloriana, the faerie queen, before they can get married. Book 2 charts the progress of the knight of temperance, Sir Guyon, culminating in the famous description of his destruction of the Bower of Bliss, an episode which has inspired commentators, artists, and writers ever since. Guyon's undoubted virtue is shown to be limited when he is defeated by the knight of chastity, Britomart, the heroine of book 3. While Guyon can only refuse and oppose bodily temptation Britomart is able to experience corporeal ecstasies and agonies, and so point to a way beyond the limits of temperance for those who have to live in the ordinary world. Britomart, in pointed contrast to the real queen of England, the virginal Elizabeth, sees her husband-to-be, Artegall, in Merlin's magic mirror, and the dynasty that she will found stretching into the future. The first edition of The Faerie Queene concluded with the striking image of the hermaphrodite created through the passionate embrace of the rescued lovers, Amoret and Scudamore, a sign that human experience could be equal and satisfying through the institution of marriage.

“The second edition of the poem (1596) is generally agreed to be a darker and more diffuse work. Book 4, the legend of Friendship, has two central figures, Cambel and Telamond, who occupy only a small section of the narrative. Many commentators argue that the original version of the poem that circulated in manuscript in the early 1580s consisted of portions of books 3 and 4, later worked into the printed version with varying success. The book contains the famous description of the marriage of the Thames and the Medway—again probably adapted from an earlier work or version of the poem. Book 5, the legend of Justice, follows the adventures of Artegall, Britomart's future spouse. This has generally been the least popular section of the poem because of its disturbing defence of English policy in Ireland and, more overtly, its historical allegory, but it has recently received far more attention for the very reason that it was previously ignored. Artegall, abandoned by his tutor, Astrea, has to resolve a number of difficult disputes, foolishly falls prey to the Amazon Radigund, and has to be rescued by Britomart before his violent suppression of rebellion in Ireland is prematurely truncated by Gloriana. Book 6, the legend of Courtesy, depicts the adventures of Sir Calidore, a confused and misdirected knight who tries to give up his elusive quest for the Blatant Beast when he stumbles across a pastoral world at odds with the courtly world he is less than keen to defend. The book, like its predecessor, is replete with disturbing images of violent disruption, principally of disguised rebels ambushing small peasant communities (undoubtedly an echo of Spenser's experience in Ireland). It ends when Calidore finally manages to capture the Blatant Beast, but it escapes to terrorize the world with its awful slanders, which include attacks on the poet himself.”(Hadfield, Oxford DNB)

ESTC S117748; STC 23082; Langland to Wither 233; Pforzheimer 970; Johnson, Edmund Spenser, 11; Luborsky & Ingram. Engl. illustrated books, 1536-1603, 23082

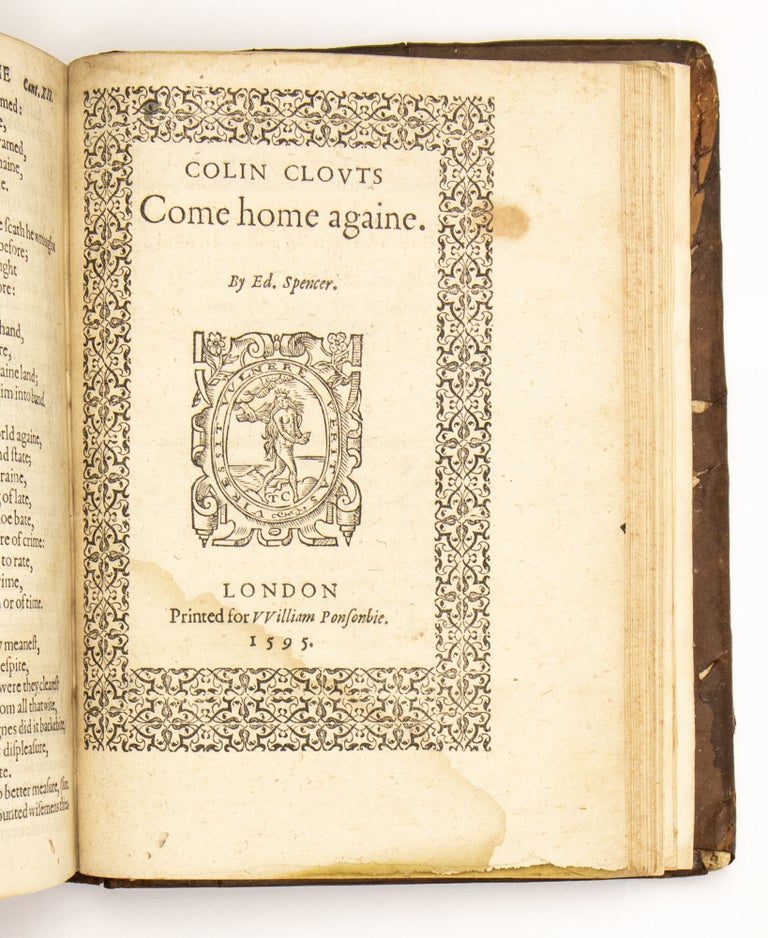

III. COLIN CLOUTS COME HOME AGAINE.

London: Ponsonbie, 1595

Quarto: [80] p. Signatures: A-K4

FIRST EDITION. The colophon reads: “London Printed by T.C. for William Ponsonbie. 1595.” With a woodcut printer’s device (McKerrow 299) and decorative border to the title page, and numerous head- and tailpieces throughout. With "worthylie" on leaf C1 recto, line 24. Moderated dampstain to first two gatherings, a little light staining thereafter, fraying to a few margins, small worm-trail in lower margin, final leaf soiled on verso.

With a dedicatory epistle to “The Right worthy and noble Knight Sir Walter Raleigh” dated “from my house of Kilcolman, the 27. Of December. 1591.” In addition to “Colin Clout”, this volume also includes Spenser’s “Astrophel: A pastorall Elegie upon the death of the most Noble and valorous Knight, Sir Phillip Sidney” (dedicated to Sidney’s widow, who had by then become the Countess of Essex); An untitled poem beginning “Ay me, to whom shall I complaine…” often referred to as “The dolefull lay of Corinda”; “The mourning Muse of Thestylis” (by Ludowick Bryskett); “A pastorall Aeglogue upon the death of Sir Phillip Sidney Knight” signed L.B. (Ludowick Bryskett); “An Elegie, or friends passion for his Astrophill” (by Matthew Roydon); “An Epitaph upon the right honourable sir Phillip Sidney Knight: Lord governor of Flushing” (by Walter Raleigh); “Another of the Same” (almost certainly by Sir Edward Dyer).

“Spenser’s “Colin Clout’s Come Home Again’, a pastoral poem in the tradition of Petrarch, was inspired by the poet’s visit to England from 1590 to 1591, a journey undertaken at the urging of Walter Raleigh. Spenser wrote the poem, dedicated to Raleigh, upon his return to Kilcolman castle in Ireland –the ‘Home’ referred to in the poem’s title.

“Spenser's adoption of an Anglo-Irish identity was publicly expressed in the title poem, where the 'home' that Colin refers to rather bitterly in the poem is Ireland, not England. At the same time, the elegies on Sidney as the English nation's poet imply Spenser's claim to be his successor.

“The poem has been called Spenser’s most biographical, and indeed it includes not only the visit from Raleigh to Spenser’s home in Ireland in 1589 but also an account of Spenser’s sea voyage and his time in England, during which he presented the first three books of his ‘Faerie Queen’ to Queen Elizabeth.

“The poem fits neatly into a tradition of advice literature that exempts the monarch from the general failings of his or her courtiers, and includes strong criticisms of the court, as well as attacks on the vanity, ignorance, and greed of courtiers in general. It is possible that Colin Clout was intended as a criticism of Elizabeth's regime in the 1590s, especially if we bear in mind Spenser's own lack of preferment in England and his posthumous criticisms of the queen in 'Two cantos of Mutabilitie'.”(Hadfield, Edmund Spenser's Irish Experience, 1997, chap. 6)

ESTC S111281; STC 23077; Langland to Wither 236; Pforzheimer 967; Johnson, Edmund Spenser, 16.