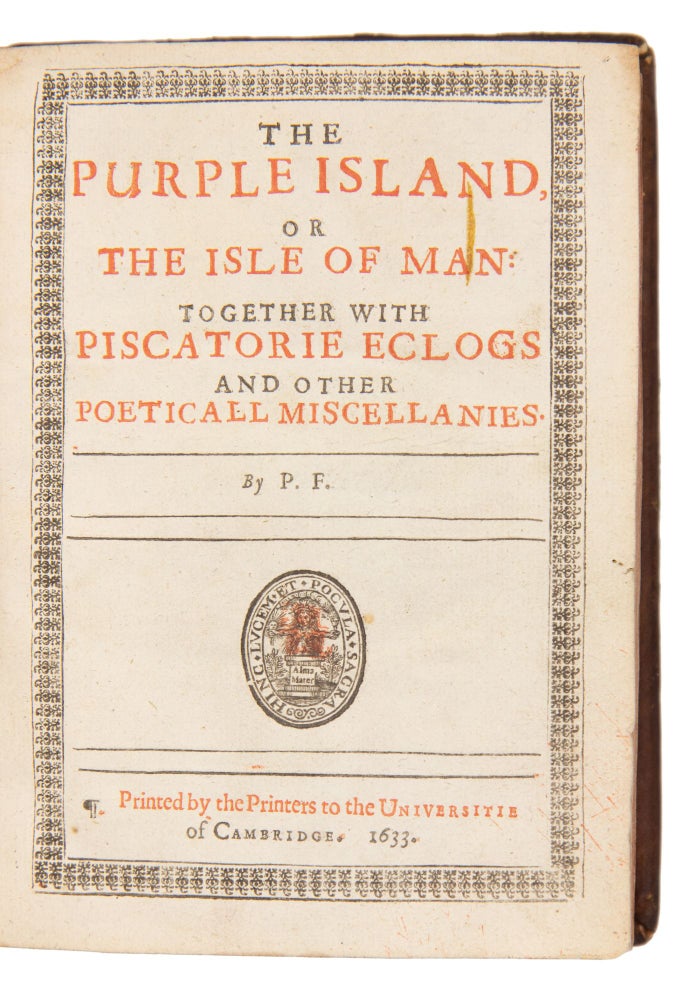

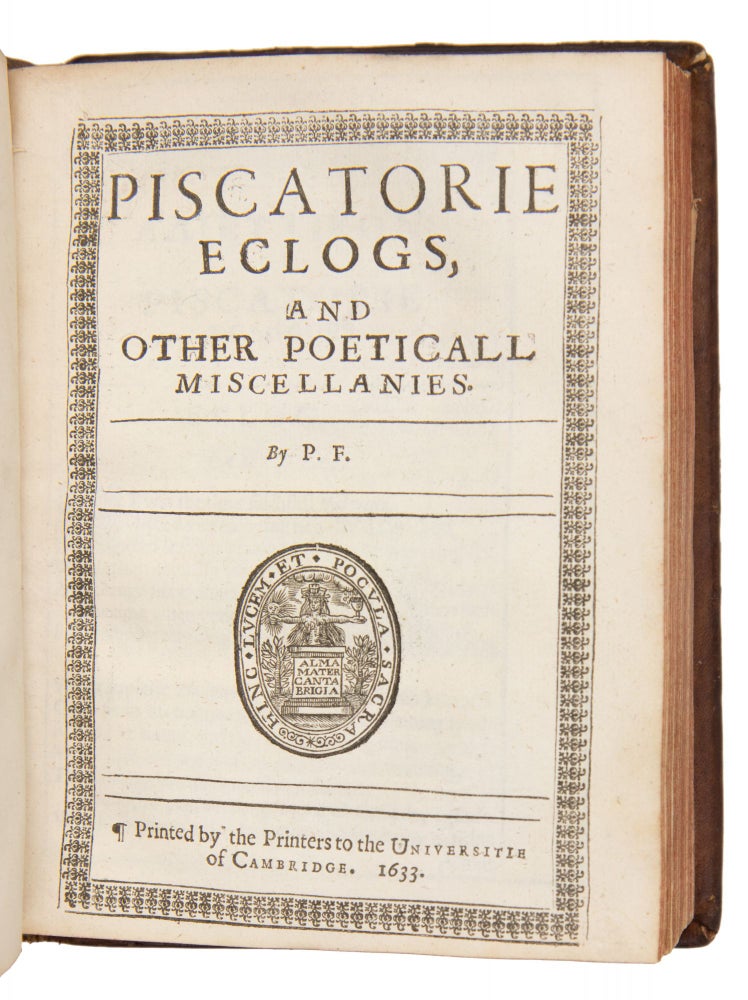

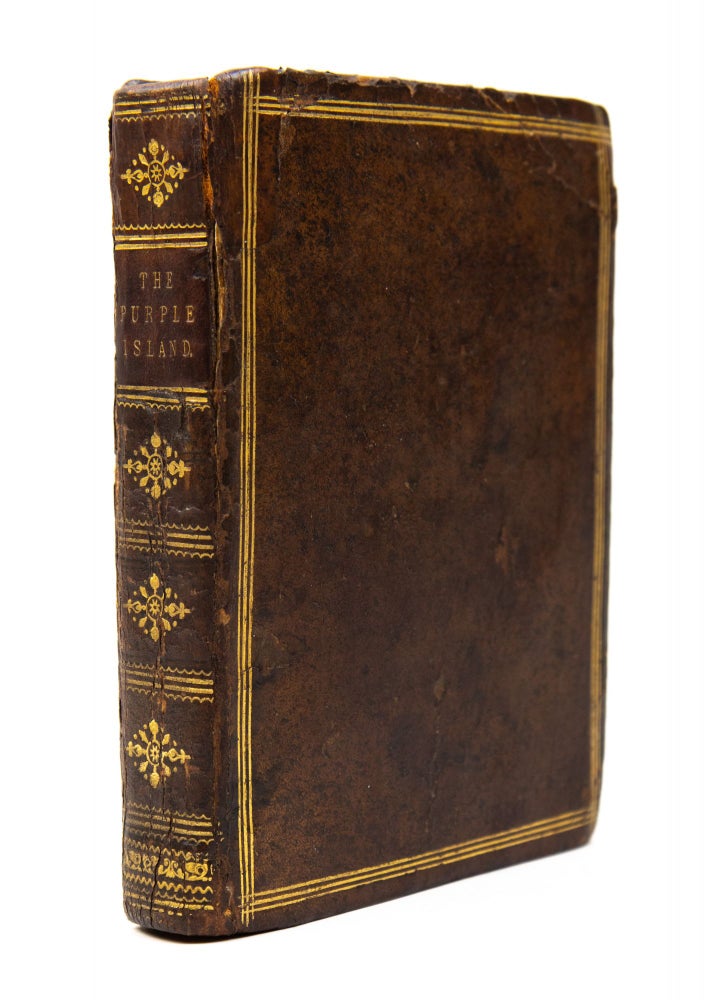

The Purple Island, Or The Isle Of Man: Together With Piscatorie Eclogs And Other Poeticall Miscellanies. By P. F.

Cambridge: ¶ Printed by the Printers to the University of Cambridge, 1633.

Price: $5,800.00

[Bound with:]

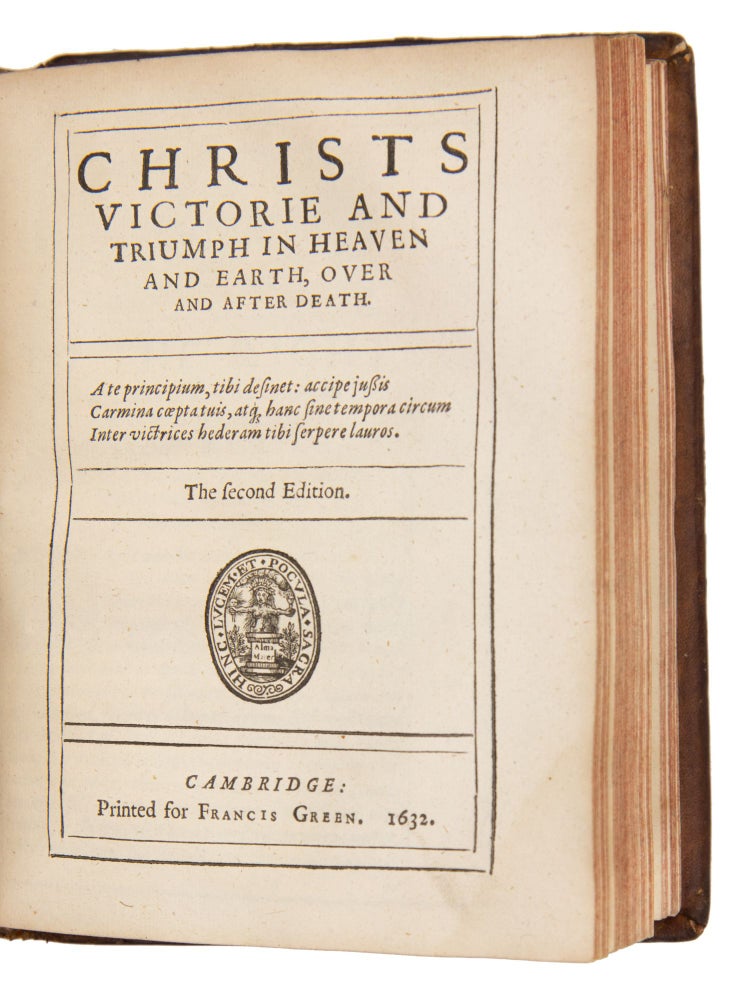

Fletcher, Giles (1585/6-1623)

Christs victorie and triumph in heaven and earth, over and after death. The second edition.

Cambridge: printed [by Thomas and John Buck] for Francis Green, 1632

[Bound with:]

Fletcher, Phineas (1582-1650)

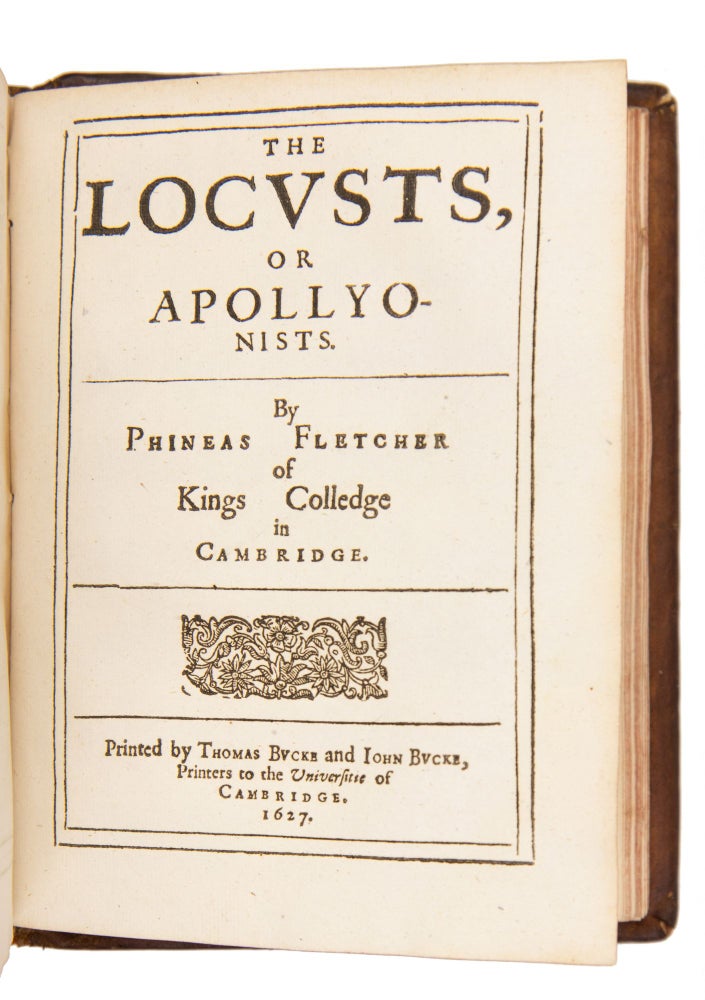

Locustae, vel Pietas Iesuitica. Per Phineam Fletcher Collegii Regalis Cantabrigiae

[Second title page:] The Locusts, or Appollyonists. By Phineas Fletcher of Kings Colledge in Cambridge.

[Cambridge]: Apud Thomam & Ioannem Bucke, celeberrimae Academiae typographos, Ann. Dom. MDCXXVII. [1627]

$5,800

Quarto: 18.3 x 1.3 cm. Three books bound as one: I. (Purple Island): [16], 181, [7], 96, 101-130, [2] p. Collation: ¶4 (-blank ¶1), ¶¶4, A-Z4, (with blank Z4 present), [chi]2 (- blank chi2), A-L4, M4, O-R4 (lvs. M3-4 mis-signed N1-2). II. (Christs Victorie): [16], 84 p. Collation: A4 (A1 blank but for device), ¶4, A-K4, L2. III. (The Locusts): [8], 100 p. Collation: ¶4 (with blank ¶1), A-M4, N2

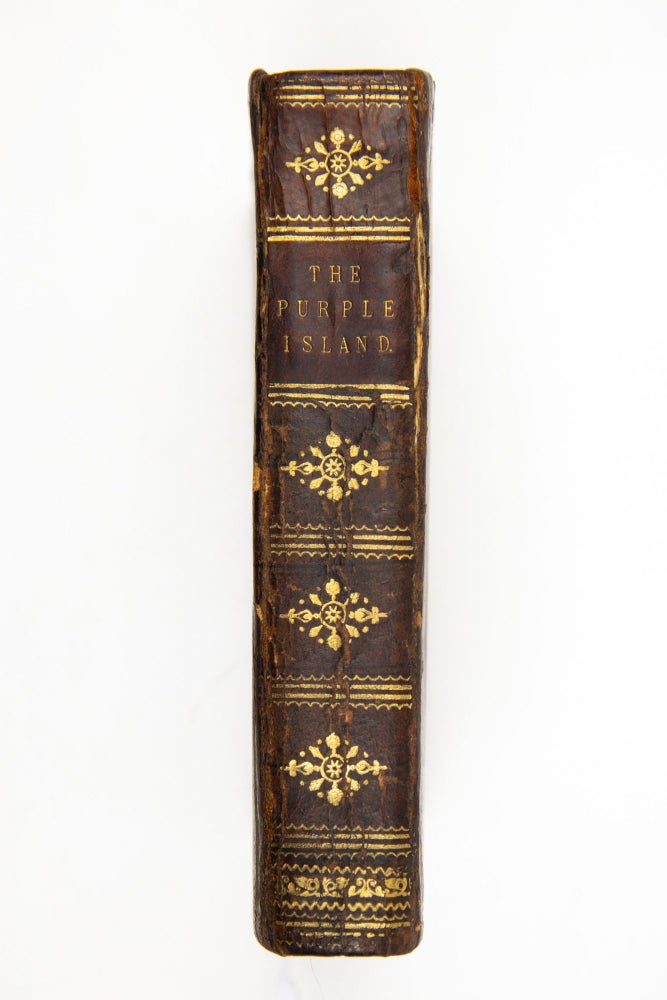

FIRST EDITION of The Purple Island and The Locusts. SECOND EDITION of Christs Victorie. Bound in contemporary speckled calf, boards framed by three gold rules, spine with gold ornaments and (later) label. Repairs to corners of upper board, hinges cracked (joints starting), small losses to spine. Internally, all three works very fresh and crisp with a few instances of the lightest dampstain. Excellent. Provenance: Robert Pirie (bookplate.)

A fine sammelband of works by the brothers Giles and Phineas Fletcher, including two verse epics: Phineas’ Fletcher’s “The Locusts” (“the most highly developed of the numerous poetic treatments of the notorious Gunpowder Plot of 1605”) and “Christs victorie” (“which should be accorded a prominent place in the history of English epic writing.”) The third work, Phineas’ “Purple Island” is an important verse allegory, with both Vesalian and Spenserian affinities.

I. “The Purple Island”

“The main part of Fletcher’s chief poem, ‘The Purple Island, or The Isle of Man’ (1633) derives from the medieval theme of the ‘castle of the body’ and develops the conceit of the island as the human body, in which the bones are the rocky foundations, the veins are brooks, and so forth, in meticulous detail based on the anatomy of Galen and Vesalius. The analogy is made by both Spenser (Faerie Queene, II. 9) and Du Bartas, but neither gives the subject Fletcher’s peculiar mixture of scientific precision and didacticism. This portion of the poem ends with an epic catalogue and an allegorical battle between the vices and virtues to which the body is subject… Although Spenser was his master, Phineas is more immediately inspired by the emblems of Francis Quarles and the metaphors of medieval science.

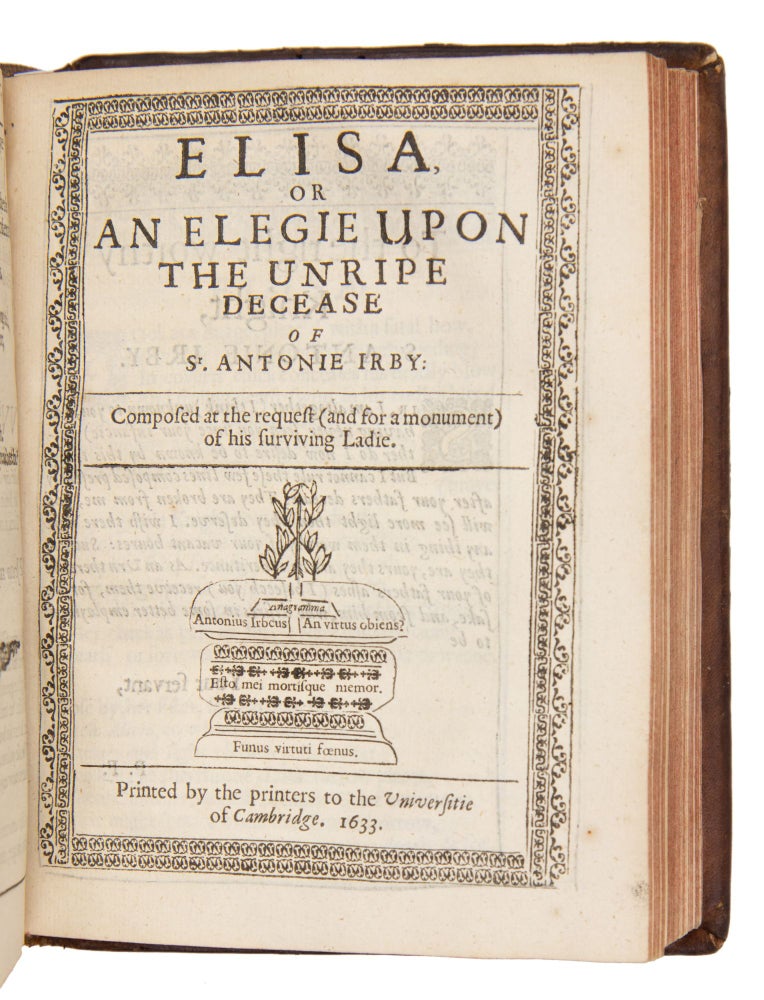

“[The book] includes seven autobiographical and ‘piscatory’ eclogues (praised by that inveterate angler Izaak Walton), epithalamia, elegies, and a concluding poem by Fletcher’s neighbor at Hilgay, Francis Quarles, who addresses him as the ‘Spenser of this age.’ Fletcher himself pays extended tribute to his master Spenser in the Purple Island. (Ruoff, Crowell’s Handbook of Elizabethan & Stuart Literature, p. 160)

ESTC S102332; STC 11082; Grolier, Langland to Wither 101; Hayward 67; Krivatsy-NLM 4121; Wellcome I,2312; Westwood & Sachell 95

II. “Christs victorie”

“Giles Fletcher (brother of Phineas) began writing poetry at a very young age, contributing some conventional elegiac verses 'Upon the Death of Eliza' to a commemorative volume on the death of Queen Elizabeth and the accession of James I (1603). His next and certainly principal work, after which he wrote almost nothing and on which his fame rests, appeared in 1610: this edition of Christs Victorie, and Triumph in Heaven, and Earth, over, and after Death was the only one published in his lifetime (there was a second edition in 1632, like the first printed in Cambridge).

Fletcher dedicates his poem to Thomas Neville, in terms effusive even for the time; then he proceeds to his prefatory remarks 'To the Reader' in which he defends 'prophane Poetrie' that nevertheless may deal 'with divine and heavenly matters'. He invokes the names of Prudentius, St Bernard, Sannazaro, and especially DuBartas and Spenser—these two last having had, indeed, the greatest influence on Fletcher; yet Grosart perhaps justly describes Fletcher 'as the pioneer of England's religious poetry in epic or semi-epic form' (Grosart, 49).

Fletcher's 'epic' is very much in his own voice, imitative in a limited way of Spenser, and only incidentally instructive to such later writers as Edward Benlowes, Joseph Beaumont, and John Milton. The work itself is somewhat discontinuous, for it is actually four separate poems, each with its own title, in two parts, with two different title-pages: 'Christs Victorie in Heaven' (part 1/1); 'Christs Victorie on Earth' (part 1/2); 'Christs Triumph over Death' (part 2/3); and 'Christs Triumph after Death' (part 2/4). There is a further complication in that the first of the two title-pages is inclusive of the whole work, the second descriptive only of the last two parts. These four poems, which might also be called cantos, are very loosely related to each other. Grundy notes that: ‘each poem pursues a different method from the rest: the first is similar to a mediaeval debate or psychomachia; the second is a Spenserian allegory; the third is a meditation on the Passion in the manner of the literature of ‘Tears’; the fourth is a sustained Christian-Platonic beatific vision.’(Grundy, 194). Thus the four parts each illustrate a different literary genre…

“He is intensely fond of antithesis, paradox, and contrasting patterns, above all of antimetabole, as in 'if any for love of honour or honour of love'. Sensuousness and rhetorical fancy, then, distinguish Fletcher's poem, which should be accorded a prominent place in the history of English epic writing.”(Stanwood, ODNB)

ESTC S121770

III. “The Locusts”

“Composed in 1611 and reworked twice prior to its publication in 1627, Fletcher’s epic is the most highly developed of the numerous poetic treatments of the notorious Gunpowder Plot of 1605. The plot was a failed attempt by Catholic conspirators, led by Guy Fawkes and working on behalf of the Jesuits and the pope, to kill James I, his family and the members of parliament by detonating gunpowder kegs beneath the House of Parliament. In the years that followed, the event served as inspiration for numerous sermons, epigrams and mini-epics.

From our standpoint, Fletcher’s poem, which is heavily indebted to Vergil for both its language and its symmetrical structure, is also reminiscent of a later English epic, Milton’s “Paradise Lost.” The portrait of Satan (Lucifer), the council of demons, the descriptions of Hell and of sin, the equation of the Vatican with Satan’s infernal palace, all find their echo in Milton’s poem. Yet it is Milton who develops Satan’s complexity of character. In Milton’s poem, Fletcher’s sentiment “O let him serve in hell, who scornes in heaven to raigne!” is spoken by Lucifer himself, drawing us into the psychology of the fallen angel, “Better to reign in hell then serve in Heav’n.”

In Fletcher’s treatment of the plot, Satan, enraged by an England at peace and by an English people faithful to God, inspires the Jesuits and the pope to assassinate King James. The poem opens with Satan summoning his infernal crew to a council. Appealing to their bravery, he proposes revenge and destruction. In response, the demon Aequivocus (Double-talker) offers to travel to Rome to ensnare the pope. The poet then sets the stage for the demon’s arrival by painting an image of Rome, replete with all her sins. Next the pope calls a conclave that mirrors that just seen in hell. During the council, a Jesuit (“Ignatius’ Eldest Sonne”) proposes the Gunpowder Plot and his suggestion meets with universal approval. To show his thanks, the pope promises a church in the Jesuit’s honor. The Jesuit then recruits his accomplices, who make the necessary preparations, hide the gunpowder and wait for the opening of Parliament. God the Father, who sends a winged messenger to warn James I with an enigmatic message, ultimately undoes the plot. James unravels the riddle and thwarts the plot. Fawkes and his accomplices are captured but remain unrepentant. The poem concludes with a hymn of thanksgiving. For a more complete discussion, see Estelle Hann’s introduction in her edition of “Locustae” (Leuven University Press, 1996)

Throughout the poem, the Jesuits strive to bring Satan’s schemes to fruition. Satan and his demons turn men’s souls to evil but it is the Jesuits who put them to work: “the Fiends finde matter, Iesuites forme; those [i.e. the fiends] bring/ into the mint fowle hearts, sear’d conscience/ Lust wandring eyes, eares filled with whispering/ Feet swift to blood [etc.]; These [i.e. the Jesuits], for Rome’s use, on Spanish anvile, frame/ the pliant matter; treasons hence diflame,/ Lusts, lies, blood, thousand griefes set all the world on flame.” (p.61)

It is a Jesuit, “Ignatius’ eldest sonne” who devises the Gunpowder Plot during the conclave. He begins his speech by criticizing the failed strategies of Cardinal Bellarmine, “who every slight and engine knows” but whose efforts have gained nothing for the Catholic cause. Instead, “Loiol’s sonne” proposes guile and underhanded tactics for winning England. He invokes Loyola as his supernatural helper, “Helpe, Ignatius. And in this act prove thy new Diety” to an act worthy of his master:

“To kill a king is stale, and I disdaine:/ That fits a Secular, not a Iesuite./ Kings, Nobles, Clergy, Commons high and low,/ The Flowre of England in one hour I’le mow,’ And head all th’Isle with one unseen, unfenced blow.”

The plot is so horrific that even the demons in Hell feel outdone by the Jesuit: “With all they envy, greive, and inly grone/ To see themselves out-sinn’d: and every one/ Wish’t he the Jesuit were, and that dire plot his own.”

ESTC S121770; STC 11081; Pforzheimer 375.