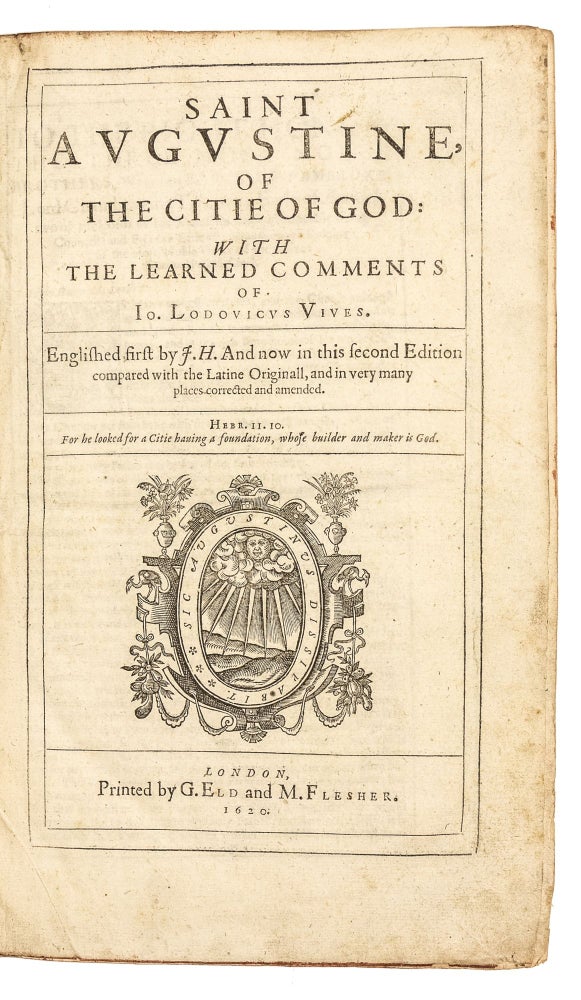

Saint Augustine, Of the citie of God : with the learned comments of Io. Lodouicus Viues. Englished first by J. H. and now in this second edition compared with the Latine originall, and in very many places corrected and amended.

London: Printed by G. Eld and M. Flesher, 1620.

Price: $8,500.00

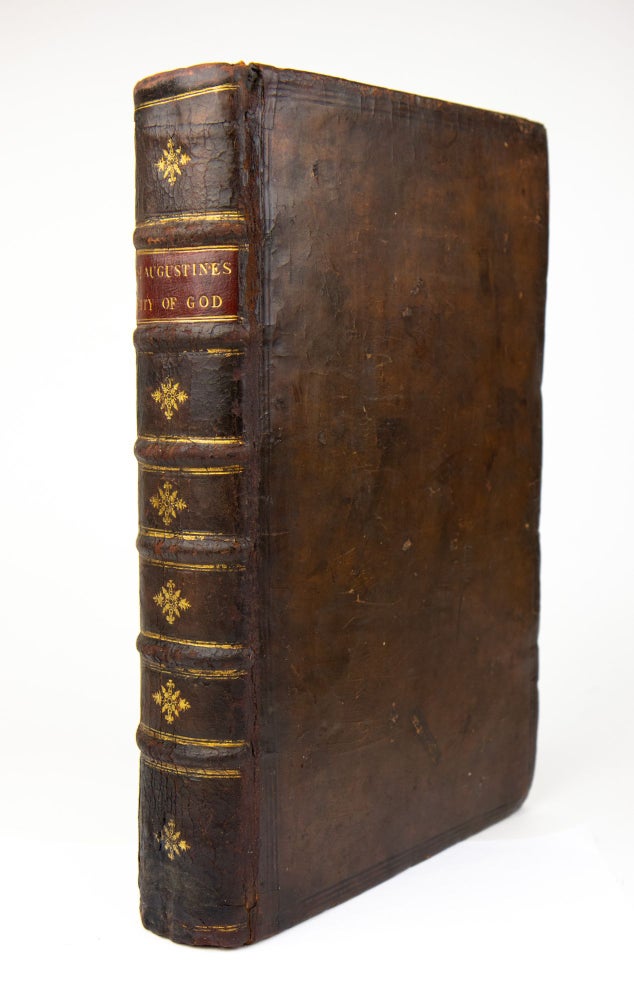

Folio: 32.2 x 21 cm. ¶4, A-Z6, Aa-Zz6, Aaa-Zzz6, Aaaa-Dddd6 (-blank leaf ¶1).

SECOND EDITION (1st 1610) of John Healy's translation of Augustine's "City of God".

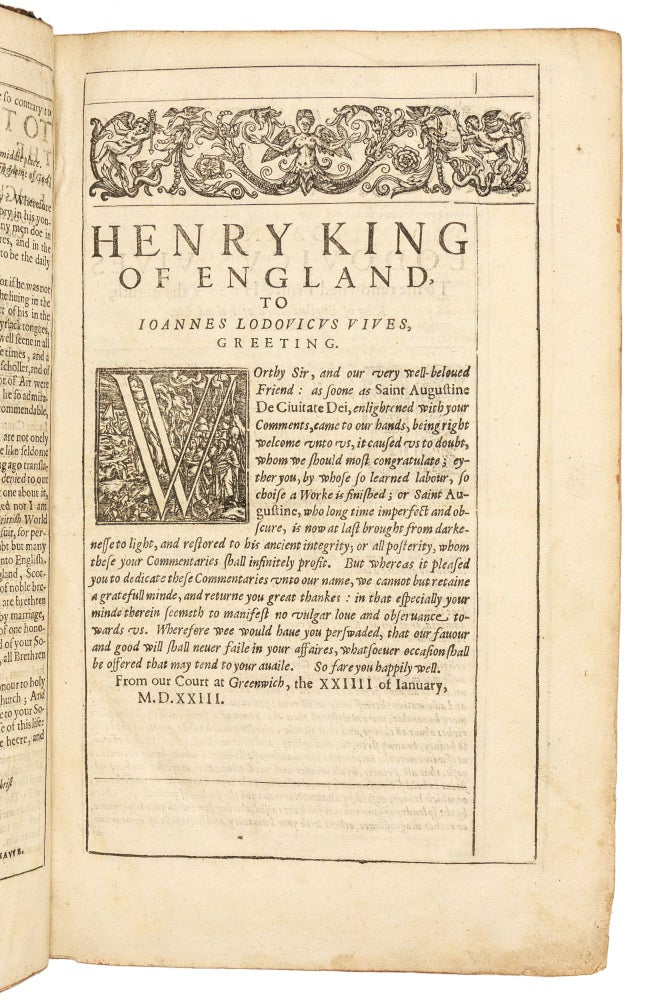

Bound in contemporary English calf, rebacked with wear to hinges; boards scuffed, corners bumped. Internally a very good copy with intermittent light marginal damp-stains, a bit darker in a few signatures. Very fine woodcut initials and headpieces. Leaves of sig. O bound out of sequence, N3 with tiny rust hole, natural paper flaw in blank margin of 2 leaves (not affecting text), small marginal paper repair to leaf Zz4.

This second edition was revised by William Crashaw (1572-1626) and includes the commentary of Juan Luis Vives (first published in Basle, 1522), which Vives wrote at the suggestion of Erasmus.

"Fifteen years after Augustine wrote the Confessions, at a time when he was bringing to a close (and invoking government power to do so) his long struggle with the Donatists but before he had worked himself up to action against the Pelagians, the Roman world was shaken by news of a military action in Italy. A ragtag army under the leadership of Alaric, a general of Germanic ancestry and thus credited with leading a "barbarian" band, had been seeking privileges from the empire for many years, making from time to time extortionate raids against populous and prosperous areas. Finally, in 410, his forces attacked and seized the city of Rome itself, holding it for several days before decamping to the south of Italy. The military significance of the event was nil--such was the disorder of Roman government that other war bands would hold provinces hostage more and more frequently, and this particular band would wander for another decade before settling mainly in Spain and the south of France. But the symbolic effect of seeing the city of Rome taken by outsiders for the first time since the Gauls had done so in 390 BC shook the secular confidence of many thoughtful people across the Mediterranean. Coming as it did less than 20 years after the decisive edict against "paganism" by the emperor Theodosius I in 391, it was followed by speculation that perhaps the Roman Empire had mistaken its way with the gods. Perhaps the new Christian god was not as powerful as he seemed. Perhaps the old gods had done a better job of protecting their followers.

"It is hard to tell how seriously or widely such arguments were made; paganism by this time was in disarray, and Christianity's hold on the reins of government was unshakable. But Augustine saw in the murmured doubts a splendid polemical occasion he had long sought, and so he leapt to the defense of God's ways. That his readers and the doubters whose murmurs he had heard were themselves pagans is unlikely. At the very least, it is clear that his intended audience comprised many people who were at least outwardly affiliated with the Christian church. During the next 15 years, working meticulously through a lofty architecture of argument, he outlined a new way to understand human society, setting up the City of God over and against the City of Man. Rome was dethroned--and the sack of the city shown to be of no spiritual importance--in favour of the heavenly Jerusalem, the true home and source of citizenship for all Christians. The City of Man was doomed to disarray, and wise men would, as it were, keep their passports in order as citizens of the City above, living in this world as pilgrims longing to return home.

"De civitate Dei contra paganos (413-426/427; City of God) is divided into 22 books. The first 10 refute the claims to divine power of various pagan communities. The last 12 retell the biblical story of mankind from Genesis to the Last Judgment, offering what Augustine presents as the true history of the City of God against which, and only against which, the history of the City of Man, including the history of Rome, can be properly understood. The work is too long and at times, particularly in the last books, too discursive to make entirely satisfactory reading today, but it remains impressive as a whole and fascinating in its parts. The stinging attack on paganism in the first books is memorable and effective, the encounter with Platonism in books 8-10 is of great philosophical significance, and the last books (especially book 19, with a vision of true peace) offer a view of human destiny that would be widely persuasive for at least a thousand years. In a way, Augustine's City of God is (even consciously) the Christian rejoinder to Plato's Republic and Cicero's imitation of Plato, his own Republic. City of God would be read in various ways throughout the Middle Ages, at some points virtually as a founding document for a political order of kings and popes that Augustine could hardly have imagined. At its heart is a powerful contrarian vision of human life, one which accepts the place of disaster, death, and disappointment while holding out hope of a better life to come, a hope that in turn eases and gives direction to life in this world.

"Augustine is remarkable for what he did and extraordinary for what he wrote. If none of his written works had survived, he would still have been a figure to be reckoned with. However, more than five million words of his writings survive, virtually all displaying the strength and sharpness of his mind and some possessing the rare power to attract and hold the attention of readers in both his day and ours. His distinctive theological style shaped Latin Christianity in a way surpassed only by scripture itself.”(Encyclopedia Britannica, 11th edition)

"Augustine’s complicated personal journey has enriched his thought with a large number of themes and starting points, which may not have found a definitive systematic placement but precisely for this reason exercise all the greater a fascination upon those periods that, like the present, shun naively integral constructions. A schoolteacher, he was brought up on texts of the classical period, and from these he got to know the best products of Greek and Latin culture. A Manichean, he came into contact with the thought of a sect that was one of the liveliest and most stimulating of the period, a sect whose importance in ancient thought is an object of careful analysis and revaluation today. A neo-Platonist, he learned deeply the lesson of the one who is for him the greatest philosopher of antiquity, Plato, and at the same time he took part in the philosophical developments of the latest current of pagan thought. In the "De Civitate Dei" he reappraises the role of Rome and her empire, yet he does not hesitate to request, in letters of impressive harshness, the aid of the state in repressing the Donatist schism. Profoundly tied to classical culture, he does not hesitate to question it in the "De Doctrina Christiana". A sophisticated intellectual, he chose to wrestle with the most complex problems, which for some time had agitated the toughest thinkers, and he also focused on new questions, ones no less anxious and difficult than the earlier ones. A man of the Church, he considered it his duty to reach the weakest and least educated of his flock, and he strove to write for all, not only for an elite of scholars. The greatest intelligences of all times have struggled with Augustine, but it is not easy to find one who has been able to interpret and to comprehend his vital difficulty without somehow diminishing it." (Gian Biagio Conte).

STC 917; Estelrich 119. Pforzheimer 19.