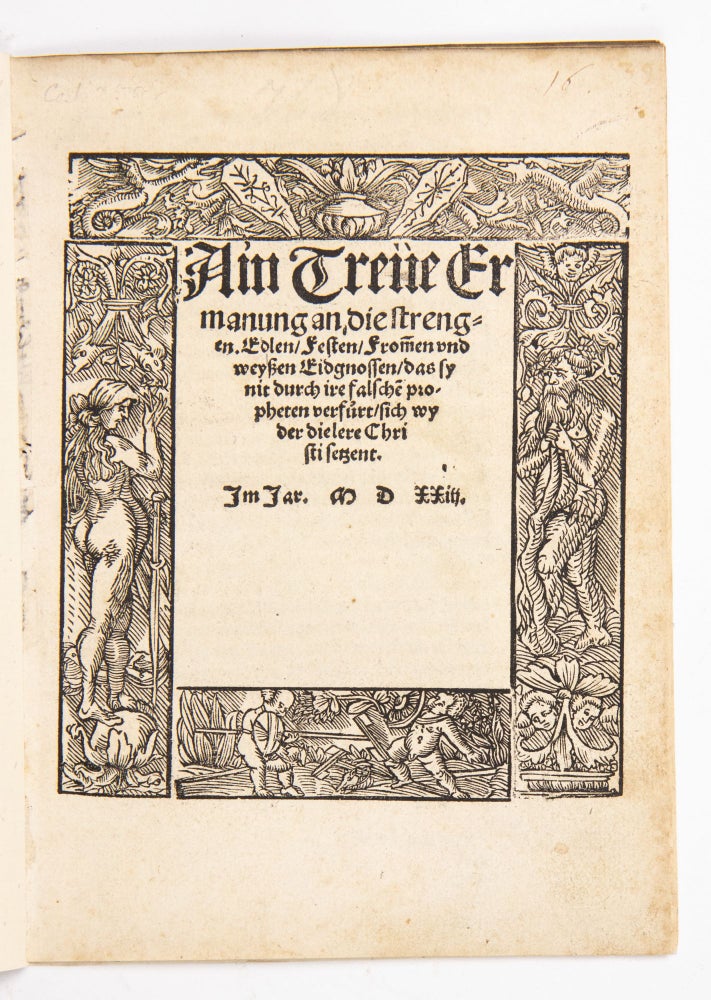

Ain treüe Ermanung an die strengen, Edlen, Festen, From(m)en und weyßen Eidgnossen, das sy nit durch ire falsche(n) propheten verfürt sich wyder die lere Christi setzent.

Augsburg: Ramminger, 1523.

Price: $3,800.00

Quarto: 20 x 14.5 cm. [24] p. A-C4. Complete with final blank.

SECOND EDITION, printed in the year of the first edition (Basel.)

Bound in modern wrappers. With a four-part woodcut “Wildman” border. Marginal foxing, light soiling.

A very rare work by Sebastian Hofmeister, an early compatriot of Zwingli and an admirer and correspondent of Luther, considered one of the most learned and rhetorically skilled of the Swiss reformers. A Franciscan friar and humanist, educated at Paris, Hofmeister was a participant in the 1st and 2nd Zurich Disputations, the Zurich colloquies with the Anabaptists, and other important theological debates. Born in 1496 in Schaffhausen, Switzerland, Hofmeister was the most important advocate of church Reform in that city.

“In February 1523 Adam Petri produced a work by Hofmeister, ‘A True Exhortation to the Strong, Noble, Steadfast, Pious and Wise Confederates, that They not be led by False Prophets to Stand in the Way of the Teachings of Christ.’ Hofmeister addressed all his compatriots, just as Zwingli would do the following year in his ‘Friendly and Serious Exhortation to the Confederates’. Hofmeister laid out a case for an end to the internal divisions within the Swiss Confederation over the issue of faith. He insisted that all hold to the pure Word of God. He defended the teachings of Luther and attacked the pope and the papacy sharply, and he called for everyone to follow the example of those who had always protected Christian freedom: ‘I ask that in future you do the same, for otherwise you will be disloyal Confederates.’ In order to recognize the true word of God one must open one's ears to reason and one's eyes to wisdom. The ‘brave Confederates of Zurich’ had opened themselves up to the Word of God: ‘You, noble Zurich, you should indeed rejoice that God has blessed you with such preachers.’ Praise for Bern followed, but a reproach for Lucerne: ‘Oh Lucerne, oh Lucerne, how your light has been extinguished ... Oh Lucerne, how you have become obdurate and have submitted yourself to scandalous shepherds.’ Now was the time to accept the word of God and follow the teachings of Christ, for one must obey God rather than men (Acts 5:29).

Hofmeister’s career:

“Until mid-1522 reformation in Schaffhausen remained an intellectual endeavor, for reformatory ideas were the province of a number of Benedictine monks and other educated men. Only with the arrival of the Franciscan friar Sebastian Hofmeister and his sermons directed towards a broader audience did the Reformation become a popular movement.

Hofmeister had been a friar in Schaffhausen and Frankfurt am Main before studying in Paris, where he was a student of Jacques Lefévre d’Étaples (Faber Stapulensis). An outstanding biblical humanist, Hofmeister quickly moved beyond the limits of Catholic exegesis. In 1516 he had become a doctor of theology. In 1520 persecution of ‘Lutheriens’ forced Lefévre d’Étaples to flee Paris, and Hofmeister, too, left the city. He became lector (Lesemeister) in the Franciscan convent in Zurich but soon moved to take up the same position in the Franciscan convent in Constance.

“His early connections with Zwingli were established during his time in Constance. In a letter to Zwingli of 17 September 1520, he expressed his high esteem for the recipient and acknowledged that he had heard Zwingli spoken of as an “outstanding preacher of the truth.” He continued, “I praise your resolution and your spirit, which is not easily changed by whatever comes your way. I am impressed by your Christian courage. I would like to fight at your side, preferably in Zurich, in order that after the capital city of our happy fatherland is freed of a sickness, the other limbs too will become healthy.” Hofmeister then asked for the understanding of his fellow religious and proposed that Zwingli be more cautious and less harsh in his judgment on monks, for under the influence of Martin Luther, himself an Augustinian friar, they would themselves come to see reason.

“Hofmeister also wrote to Luther from Constance. In a letter of 3 November

1520 he offered Luther his friendship, according to humanist convention,

and encouraged him to continue with his work of reformation. “Do continue, friend of Christian freedom! Nothing must hold you back!” Luther, he wrote, would find support “among us Swiss. It is wonderful to see how greatly these men love you, how they deem you worthy of their protection because of your learning.” Hofmeister wrote later of his great joy at being honored with a reply from Luther, but unfortunately Luther’s response is no longer extant.

“At the beginning of 1522 Hofmeister was again transferred and took up the

position of lector at the Franciscan convent in Lucerne. On 29 January 1523, at the first Zurich disputation, he recounted that in Lucerne he had preached the gospel to the best of his ability and with all possible effort. He had proclaimed “nothing other than the Word of God, holy scripture.” His effort, he noted, had brought him not just friends, but also many enemies, who deemed him to be “a defiant, arrogant little monk.” But in 1520 pointed polemic against Luther was already to be heard in Lucerne. When Hofmeister preached against the veneration of Mary and the saints and against a variety of church traditions, he was accused of heresy… He had to flee Lucerne and after a short stay in Zurich, he returned to Schaffhausen at the end of May or beginning of June 1522 in order to preach the gospel in his hometown.

“Hofmeister worked in the parish church of St. John and in the monastery

of St. Agnes, churches long served by Franciscans. Adopting the principle of

sola scriptura, he preached the message that the godless would be justified by faith alone. In this stance he was a true pupil of Zwingli, who also strongly influenced Hofmeister’s teaching on the Lord’s Supper: the body and blood of Jesus Christ are “enjoyed and received in a spiritual way and through faith.”

“Well-educated and a powerful preacher for the masses, Hofmeister brought about the reform of worship in Schaffhausen in line with the Reformation. “All pomp and ceremony disappeared,” it was recorded: a new spirit was blowing in Schaffhausen. Hofmeister quickly found many followers among the city’s inhabitants, but at the end of 1522 he also faced significant opposition, for, whether on religious or political grounds, conservatively minded adherents of the old faith rejected all innovation.

Hofmeister maintained his ties with Zwingli, and he took part in the first Zurich disputation. In a letter written on the first Saturday after Easter 1523 he reported to Zwingli that the gospel had taken root in Schaffhausen. “Here Christ is accepted with the greatest longing, God be praised,” he noted, continuing that many people in Schaffhausen who had once been the sharpest of enemies of the true faith “are seeing reason. I myself preach with good signs for the future. Our council has promised me protection against the pope. I am to preach only what is pure, which is entirely in accordance with my own convictions.”(Bryner, the Reformation in Schaffhausen)

After the Peasants’ War (1524-1525), when the Catholic party won control of the city, Hofmeister was sent to the University of Basel to be examined on his orthodoxy. Considered a fomenter of disturbances, the City Council alleged that Hofmeister “had often preached from the pulpit that the Mass was an invention of the devil, and that infant baptism was not valid.” Unable to return home, he found a friendly reception in Zürich. His career as an influential reformer continued, unabated.

VD 16, H 4307; Kuczynski 1043