De sacramentis Christianae fidei.

[Augsburg: Günther Zainer,] c., 1477.

Price: $20,000.00

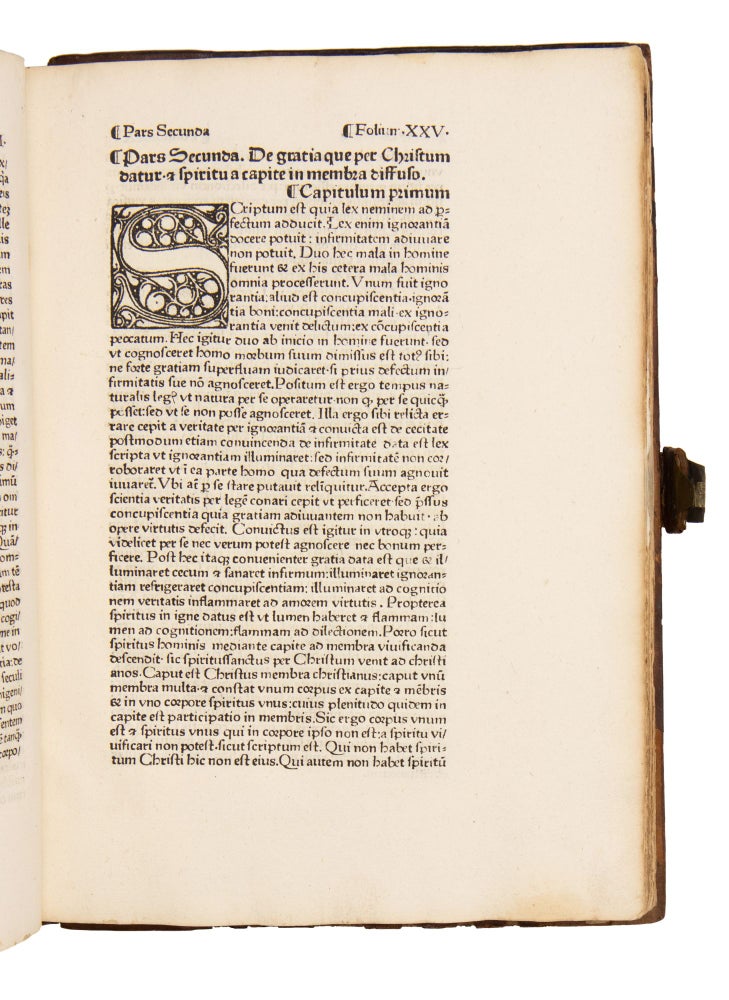

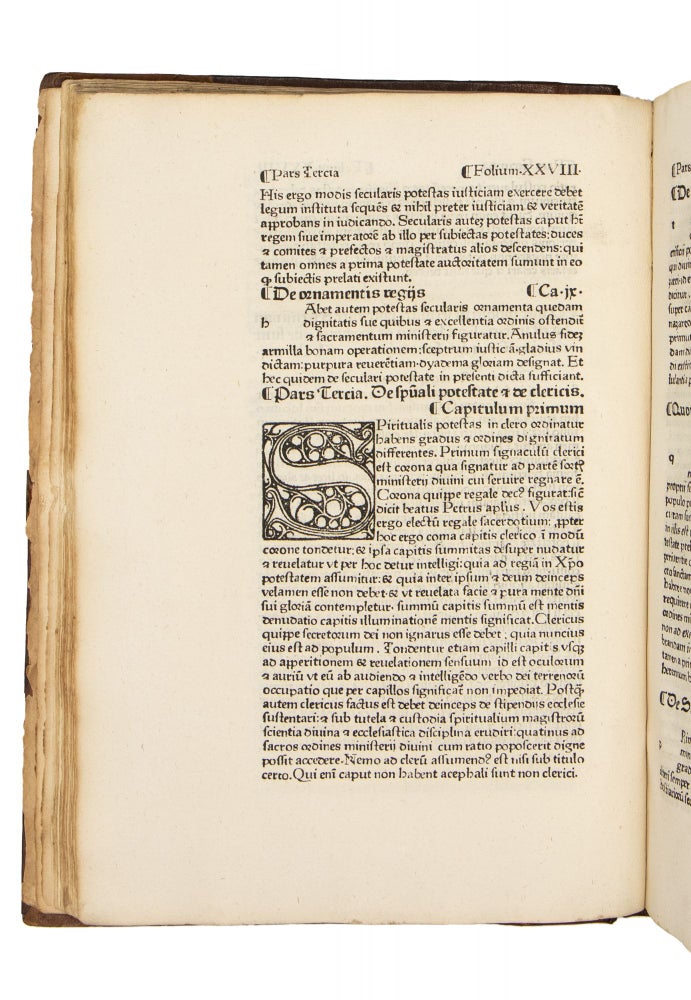

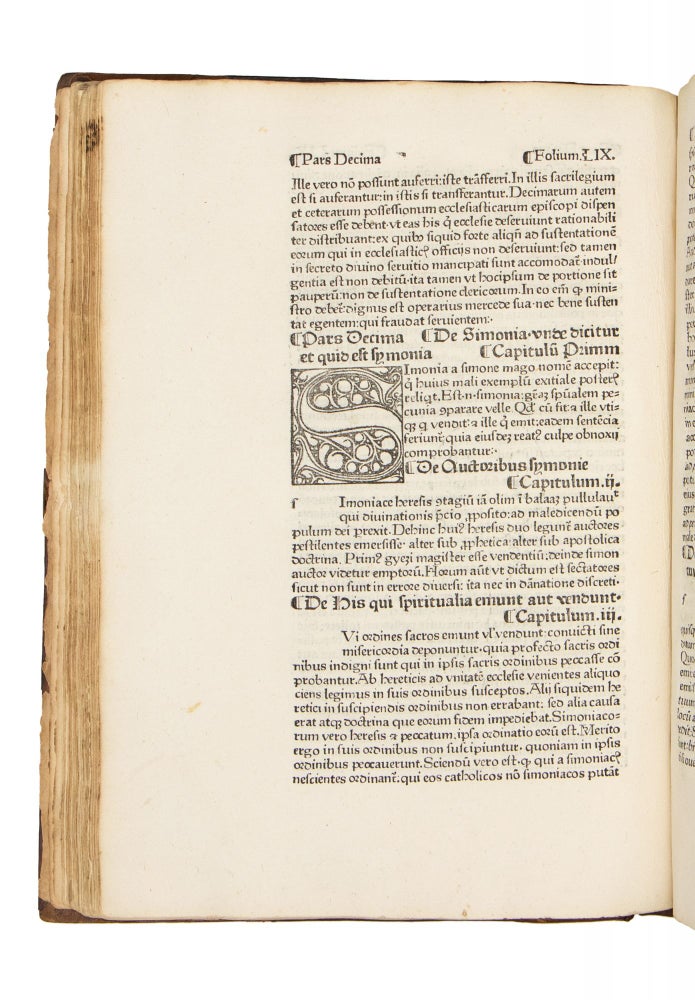

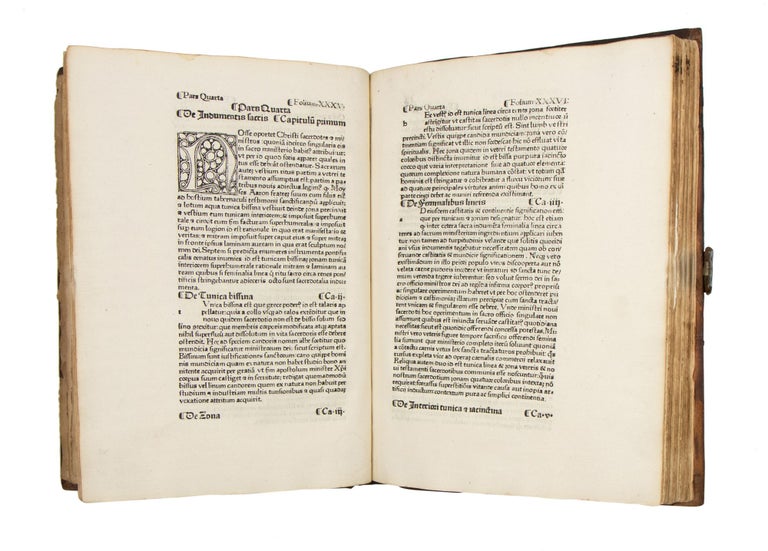

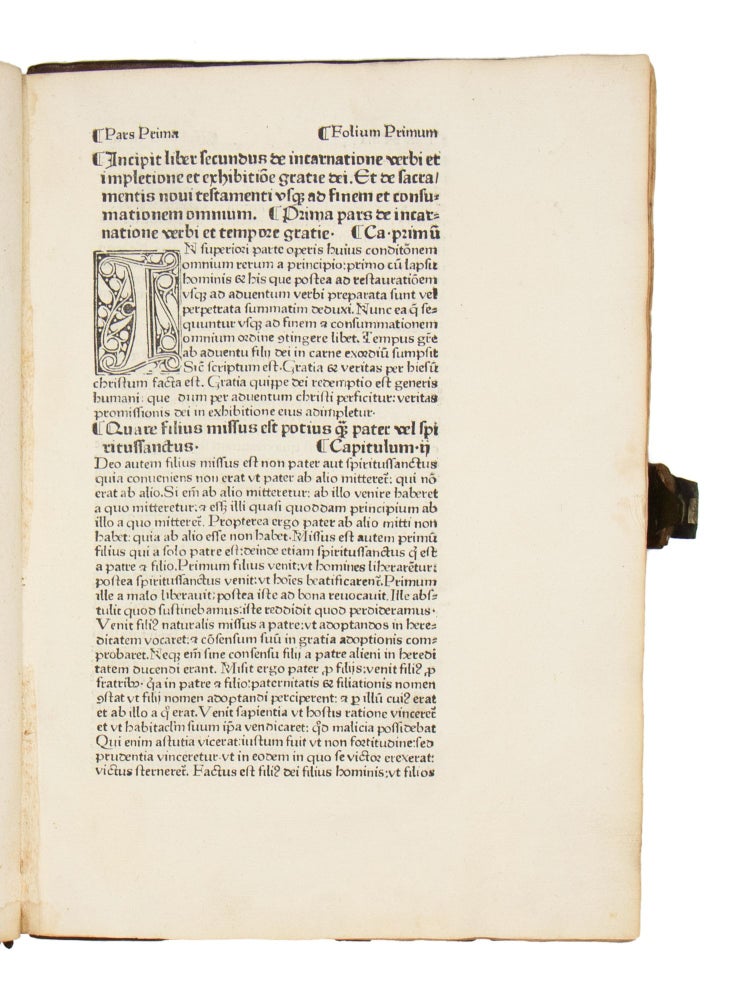

Chancery folio: 28.5 x 20.4 cm. 141 leaves (of 142, without initial blank). Collation: A6, a-n10, o6 (- blank A1)

FIRST EDITION.

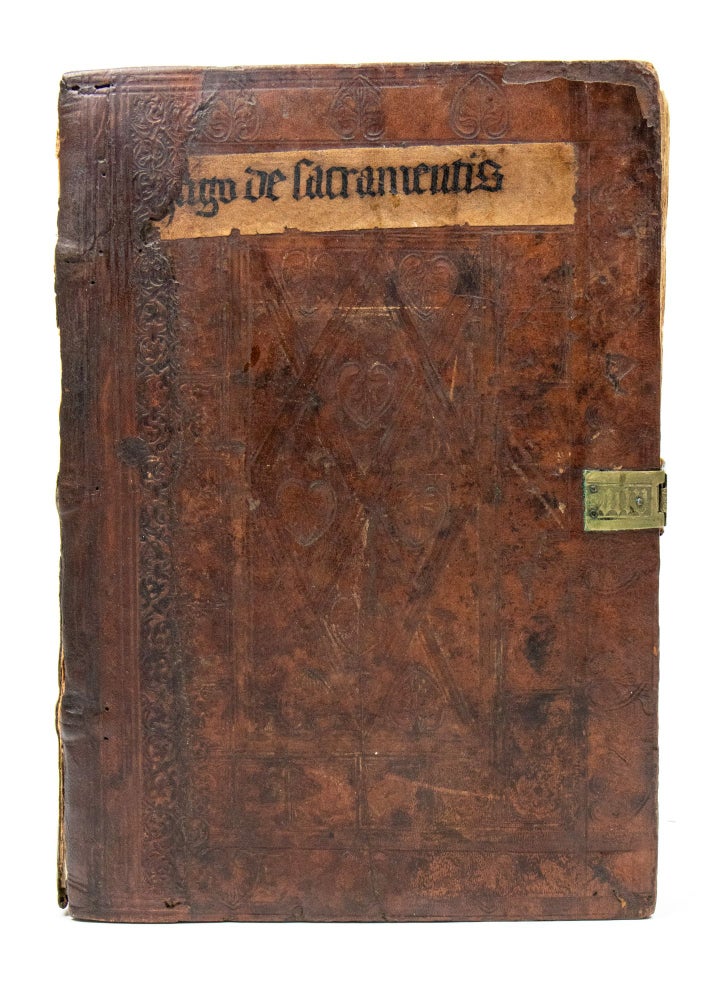

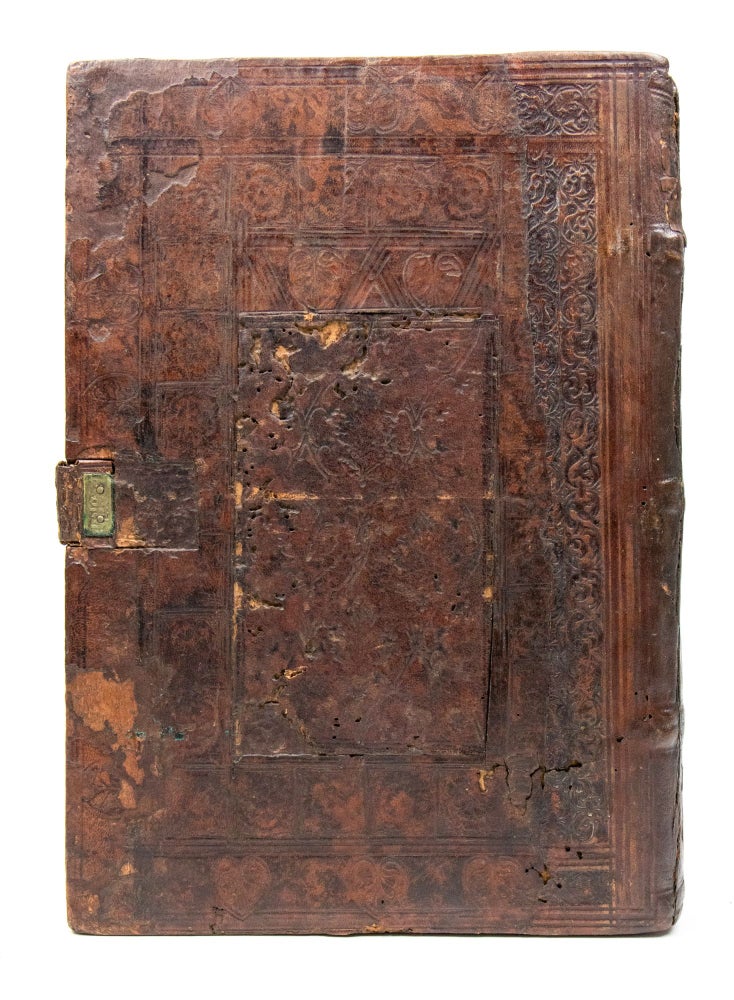

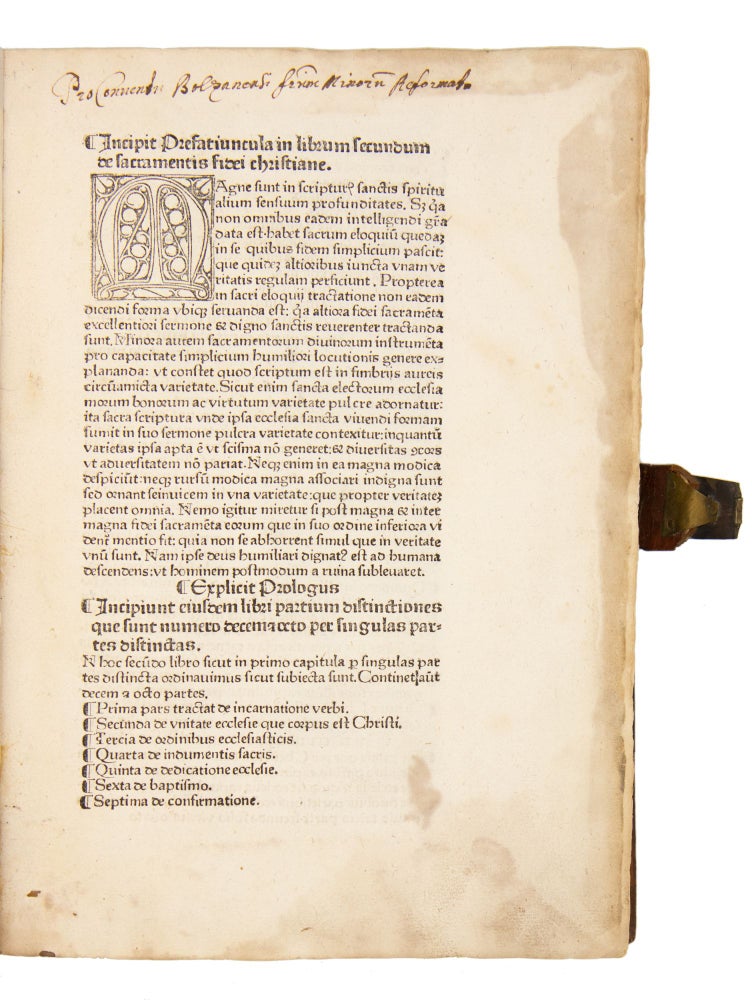

Bound in contemporary blind-tooled calf over wooden boards, the brass clasp with catch-plate preserved. An original title on label on upper board is preserved, with slight loss. The binding has been rebacked and has some other minor restorations; the lower boards is a bit wormed. A fine, broad-margined copy, with just a little marginal worming to the first and final few leaves (not affecting the text); light dampstain to the lower corner of first 4 leaves; discoloration to the margins of the final two leaves. The text is adorned with large, attractive woodcut initials throughout. Provenance: Engraved bookplate of the Bozner Franziskanerkloster, the Franciscan friary of Bolzano, South Tyrol (Trentino-Alto Adige), acquired by Elaine and Alexandre Rosenberg from H.P. Kraus, New York, 4 May 1955.

Hugh of St. Victor’s ‘De sacramentis Christianae fidei’ (On the Sacraments/Mysteries of the Christian Faith), marks an important stage in the early development of systematic theology. It is the first of the medieval summa, a form that would flower in the next century and reach maturity in the work of Aquinas. Hugh’s outline for this doctrinal masterwork is salvation history itself, from institution (creation) to restoration (salvation) as centered on the incarnation and as yet to be fulfilled. This edition comprises Part II of the work; Part I was not printed until 1485, by Georg Husner, at Strasbourg.

“Hugh of St Victor principal work, ‘De sacramentis Christianae fidei’, represents a watershed in the history of Christian sacramental theology. It gathers together much of the Western Church’s prior understandings of the sacraments, especially those of Augustine and Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, systematizes and amplifies them, and betokens later developments by thirteenth-century scholars such as Thomas Aquinas and Bonaventure. It was written just after Hugh became prior of the influential Augustinian abbey of St Victor, Paris, in 1133. In ‘De sacramentis’, Hugh depicted the Christian experience as a process of restoration within human history situated in the Incarnation, effected by means of the sacraments, and ultimately completed in the union beyond history of the individual with God.

“Hugh codified the various sacraments into a sophisticated taxonomy which included both temporal and theological axes. Heilsgeschichte consisted of three discrete and chronological dispensations: the time of ‘Natural Law’ (Creation to Moses), ‘Written Law’ (Moses to the Christevent) and ‘Grace’ (Christ-event to the Consummation). Theologically speaking, the sacraments in each dispensation comprised three types:

those which were preparatory to salvation; those which were beneficial, but not imperative; and those which were essential to salvation. Those necessary for salvation in the dispensation of grace included ‘faith’, ‘the sacraments of faith’ (that is, the seven so-called ‘liturgical’ sacraments) and ‘good works’…

“A clear understanding of Hugh’s sacramental theology in ‘De sacramentis’ is impossible without first a proper knowledge of his nuanced use of the Latin term sacramentum. ‘Now we must understand,’ he averred, ‘that we ought not to believe that all [sacraments] are sacraments.’ At the foundational level, a sacramentum was either an empirical representation and/or an indicator of a metaphysical reality. It could take the form of either a material element, physical action or spoken words. In short, a sacrament was a sign (signum), to use Hugh’s favourite synonym. It was extremely important for Hugh, however, to differentiate between three broad interpretations for the word: profane sacraments, sacred sacraments, which impart grace, and sacred sacraments which do not.

“At a basic level, there were both profane and religious sacraments (sacramenta). Sacraments of non-Christians (‘infidels’), ‘military sacraments’ and ‘sacraments of the devil’ constituted some of these profane sacramenta which are occasionally mentioned in ‘De sacramentis’. Perhaps these were references to the word’s more prevalent, extra-ecclesiastical meanings in the Middle Ages such as an ‘oath’ (military, civil or private), ‘solemn engagement’ or ‘initiation’.

“But more pervasively for Hugh, sacramentum designated a sacred sign or sign of a religious reality. Not all sacred signs were alike, however. ‘One thing is a sacrament only by signifying sanctification and by sanctifying through sanctification; another, not by sanctifying but by signifying only’. In other words, some sacred signs conferred ‘grace’ (gratia) by means of the Holy Spirit and others did not. Hugh understood ‘grace’ as a metaphysical enlightenment, extraordinary anointing or supernatural strengthening. ‘Virtue’ (virtus), Hugh’s synonym of choice, referred not to a moral or aesthetic quality but to spiritual power. It was only since the completion of the Christ-event that humans had access to virtue-conferring sacraments; prior to that time, in the first two dispensations, no sacrament could confer this grace.‘ In the third dispensation, the seven liturgical sacraments (Hugh’s ‘sacraments of faith’) and a certain higher order of the sacrament of faith composed the virtue-conferring sacraments. Good works and a lower order of the sacrament of faith did not bestow virtue, but were, nevertheless, efficacious sacred signs on their own terms as a means of God’s restorative action. Their primary function was to increase religious piety or devotion. Although such a two-fold differentiation of sacramentum was implicit in an inchoate form in Augustine, Hugh was the first Christian theologian of significance to distinguish between a ‘sacrament’ proper and a ‘sacramental’….

“In light of the subtlety and complexity of Hugh’s sacramental theology as contained in the encyclopedic ‘De sacramentis’, it is little wonder that medieval scholar Marie-Dominique Chenu characterized him as ‘that master of sacraments and sacramentalism’. The sacraments for Hugh constituted an integral part of that series of activities in the life of the Christian believer which fulfilled divine imperatives. Within each of the sacraments required for salvation, faith, the liturgical sacraments and good works, there was a discernible order of priority, divinely ordained. But together, these three operated in harmony, without disparity in significance, to affect spiritual transformation and to affect God’s ‘work of restoration’.”(Girolimon, Hugh of St. Victor’s ‘De sacramentis Christianae fidei: the Sacraments of Salvation, in The Journal of Religious History, Vol. 18, No. 2, December 1994)

The early Scholastic theologian and mystic Hugh of St. Victor (c.1096–1141) left a large and influential corpus of works on all aspects of theology, as well as the liberal arts broadly defined… “Hugh’s encyclopedic interests include grammar and geometry, philosophy and all of theology, history and eschatology, Job and Mary, the sacraments broadly and narrowly defined, spirituality, and the Dionysian Celestial Hierarchy. How he held all this together in his thought and corpus is a challenge to modern (and postmodern) readers.”(Rorem).

ISTC ih00536000; Goff H-536; HC(+Add) 9023*; GW 13630; BMC II 325; BSB-Ink H-434; Bod-inc H-243