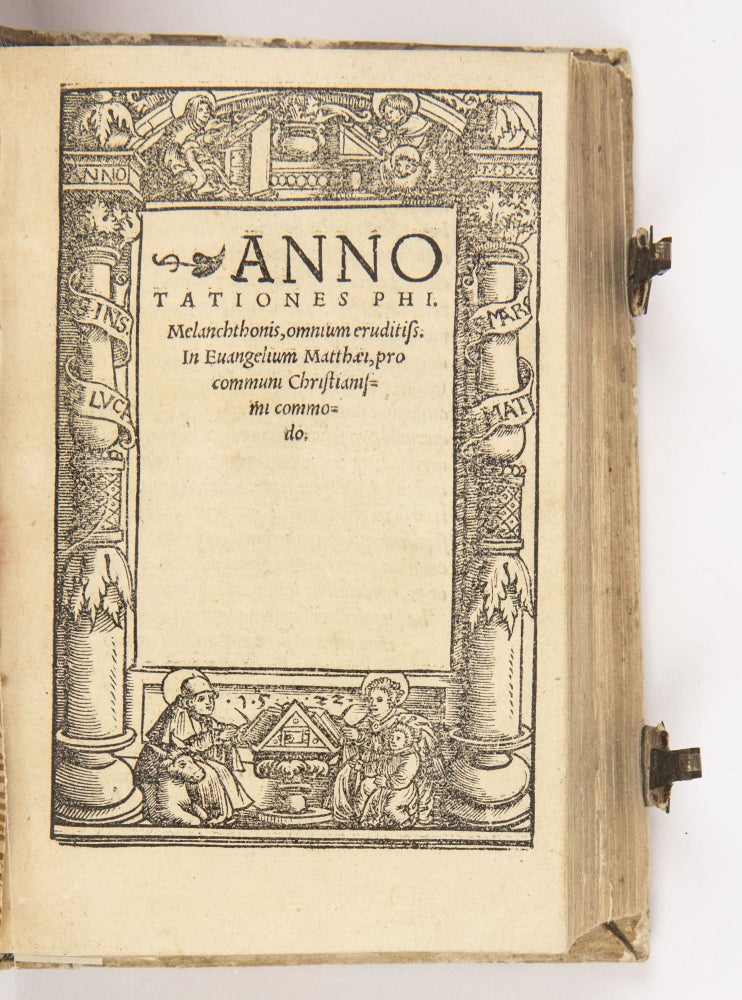

Annotationes Phi. Melanchthonis, omnium eruditiss. In euangelium Matthaei pro communi christianismi commodo.

Tübingen, Ulrich Morhart the Elder, June, 1523.

Price: $7,600.00

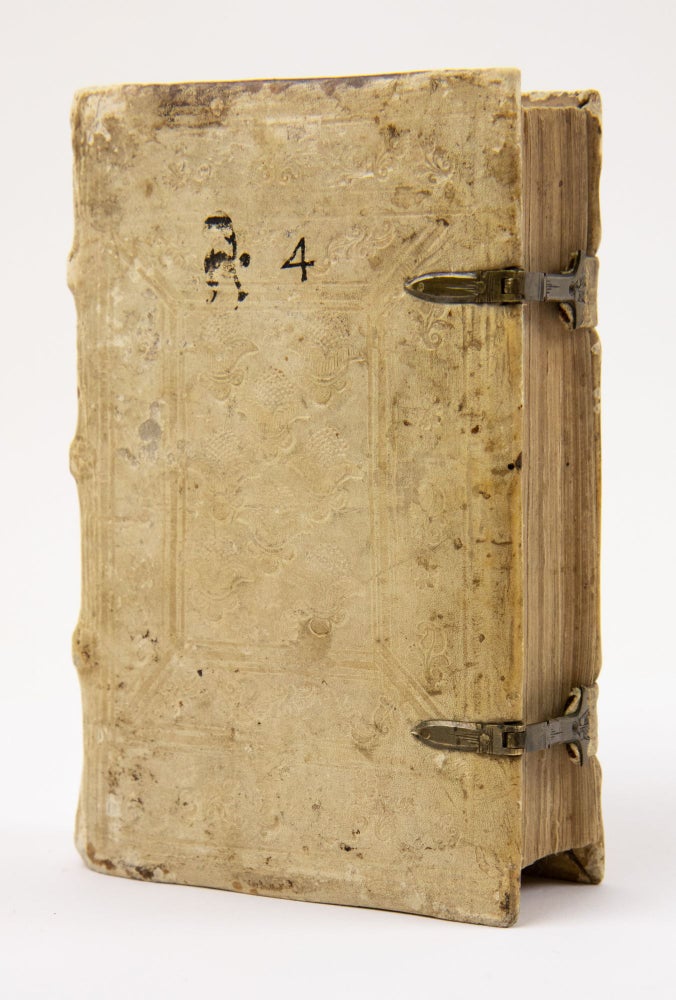

Octavo: Three works bound as one. 14.5 x 10.2 cm. 56 lvs. Collation: A-G8. With a title border with the Evangelists.

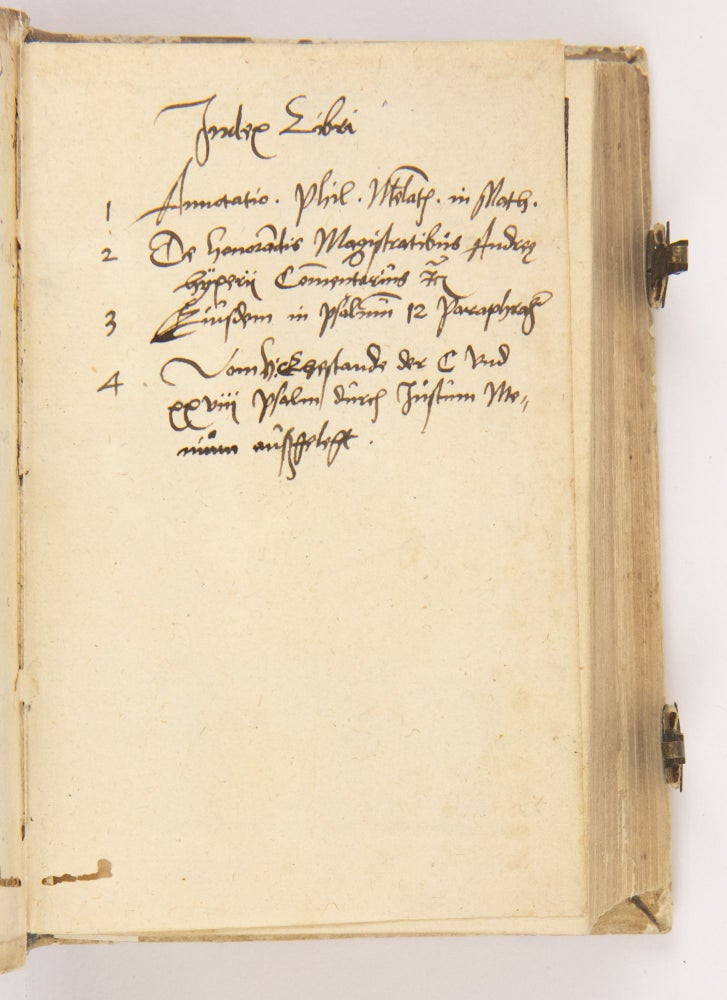

Three works bound in contemporary alum-tawed pigskin over wooden boards, ruled and stamped in blind, both clasps intact, with light stains and smudges. The text is in excellent, crisp condition, the last three leaves with a slim worm trail affecting a couple of words on each leaf. Contemporary manuscript index on front free endpaper. A beautifully preserved sammelband, featuring an early edition of Melanchthon's lectures on the Gospel of Matthew, and first editions of works by the Flemish theologian Andreas Hyperius (Gheeraerdts) and Justus Menius.

I. Melanchthon’s Annotations on Matthew:

ONE OF NUMEROUS EDITIONS IN THE YEAR OF THE FIRST (Wittenberg).

“On 19 September 1519 Phillip Melanchthon (who had arrived at Wittenberg the prior year) was promoted to Bachelor of Bible on the basis of successfully defending theses ten days ear¬lier. He was thus licensed to lecture on the content of the Latin text of Scripture, although he also continued to lecture on the Greek text. He began with lectures on Matthew (1519–1520), followed by lectures on Romans (1520–1521), 1 & 2 Corinthians (1521–1522) and John’s Gospel (1522–1523). When Martin Luther forced publication of the Pauline lectures in 1522 and the lectures on John in 1523, an enterprising printer in Basel also published the lectures on Matthew. These annotations were part of Wittenberg’s effort to produce commentaries on nearly the entire New Testament.”(Wengert)

“When Melanchthon entered Luther's Wittenberg in 1518, his intellectual development was that of so many other young humanists: he was well trained in Latin, was strongly attracted to Greek studies but had received a quite traditional education in scholastic philosophy. In his bags he carried not only copies of Aristotle's (duly glossed) main works, but all of Erasmus’ revolutionary books which advocated the study of bonae litterae for their civilizing power, and especially for their impact on the correct study of the Bible and the Fathers. Melanchthon had been called to Wittenberg to occupy the chair of Greek language and literature at the University. Very quickly, he came under the influence of Martin Luther, although their characters seemed to have nothing in common; for one thing, Luther was an impressive, violent man, whereas Melanchthon was a shy young boy with a wavering voice. In spite of this, their friendship and collaboration lasted a lifetime.

“[Melanchthon’s] parallel study of classical and biblical sources will remain one of the most striking features throughout Melanchthon's career as a classical scholar, a ‘Martinian’' theologian, and a reformer of Germany's schools and Universities. More precisely, he used his exceptional abilities as a reader and commentator of Greek and Roman sources to reshape theology along humanist lines. This means, that his analysis of classical literature, especially oratory, provided him with an analytical method on which he based, first, his exegetical efforts and, secondly, his "dogmatic" theology. Making Luther's sola scriptura principle his own, he insisted that theology should have its foundation in a careful, methodical reading of the Bible, never the other way around. He claimed that the traditional body of knowledge of the Church, built up by the Fathers and by medieval theologians, could only be accepted as far as it did not contradict the basic truths he had discovered by his methodical reading.”(Meerhof)

This edition of Melanchthon’s “Annotationes” is one of the first books printed by Ulrich Morhart at Tübingen. Morhart had printed at Strasbourg from 1519 to 1523. The ornamental Evangelist title border of 1522 is described in Steiff (Erster Buchdruck in Tübingen, p. 30).

II. Hyperius (Gheeraerdts), Andreas (1511-1564)

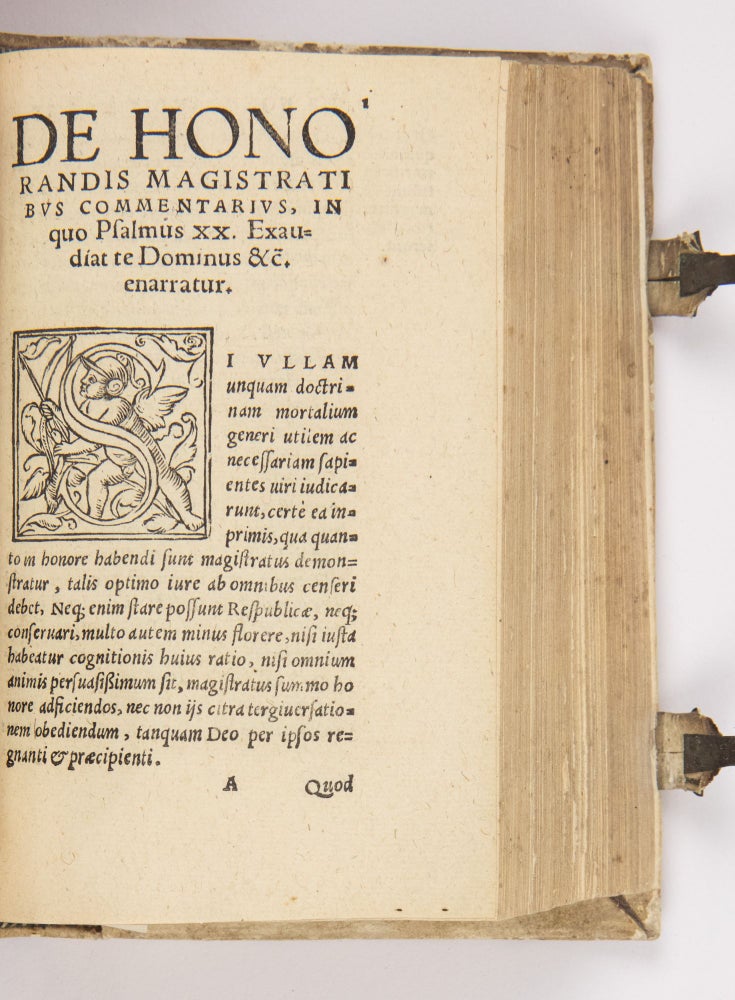

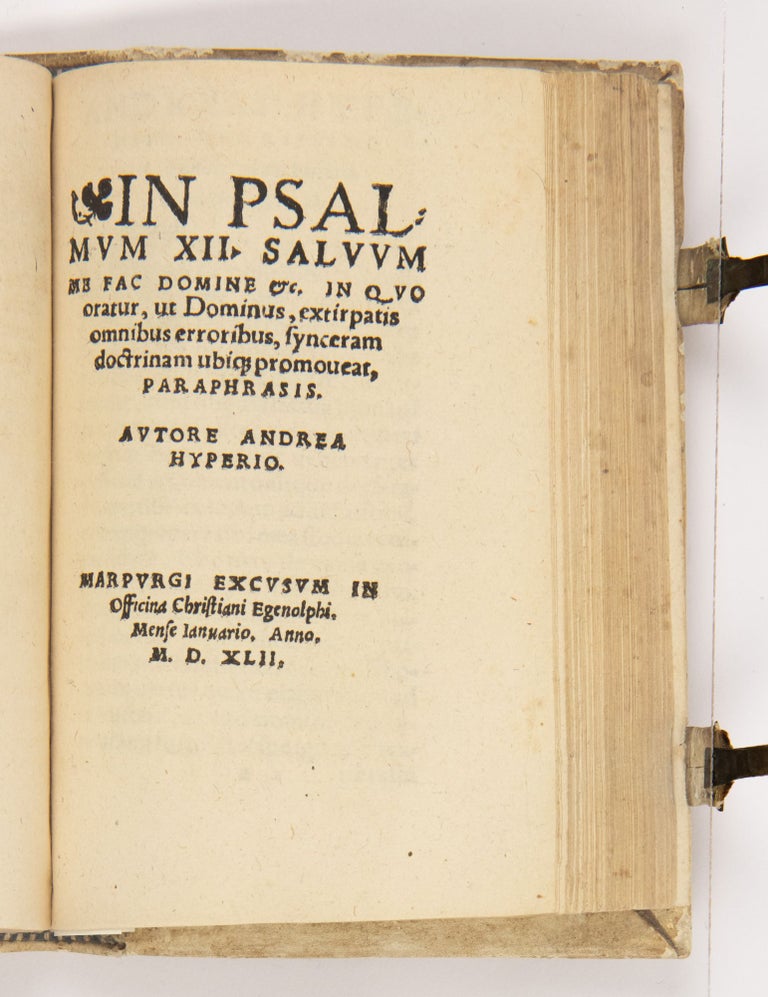

De Honorandis Magistratibus Commentarius, in quo Psalmus XX. Exaudit te Dominus &c. enarratur ... Eivsdem In Psalmum XII. salvvm me fac Domine etc. In quo oratur, ut Dominus extirpatis omnibus erroribus, synceram doctrinam ubiq(ue) promoueat, Paraphrasis.

Marburg: Christian Egenolph, Januar 1542

FIRST EDITION of this commentary on the psalm XX, “On Honoring of Magistrates”, and a paraphrase of Psalm XII by the Flemish theologian Andreas Gheeraerdts, who had lived in England from 1536 to 1540. He was appointed professor of theology at the University of Marburg in 1541, where he taught until 1564.

“Hyperius's theology lies between Lutheran and Reformed beliefs. Influenced by Martin Bucer, he was not a strict Lutheran. Jean Calvin endorsed his erudition. In his overall approach, Hyperius sought a firm basis in the Bible, rigidly, and held that before practical theology can be put in force, it must be made a part of systematic theological study, and must not be taught fragmentarily. Demanding an immense amount of preliminary reading on the part of the student, covering all practical theology except missions, he held that such reading would involve preparation for the practical work of the ministry. All must be squared with the Bible, or, where the Bible did not contain specific data, with the commandments of love for God and one's neighbor.”

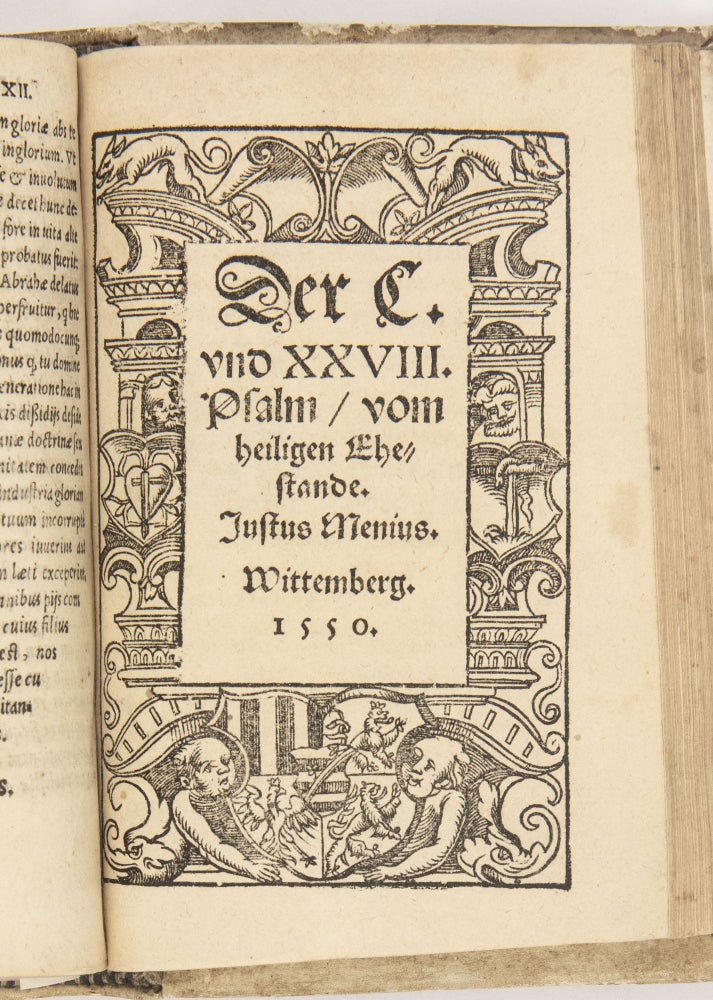

III. Menius, Justus (Jost Menig) (1499-1558)

Der C. vnd XXVIII. Psalm / vom heiligen Ehestande.

Wittenberg: Veit Creutzer, 1550

First edition of the sermon on the 128th psalm, “On Holy Marriage”, by Justus Menius (1499-1558) Menius, who is best remembered as a bitter opponent of the Anabaptists, considered marriage and parenthood as the greatest of God’s vocations, and, not surprisingly, advocated clerical marriage.

In 1514, Menius entered the University of Erfurt, Germany, and joined the circle of Humanists around his uncle Mutianus Rufus and Crotus Rubianus. In 1519, his fellow humanist, Phillip Melanchthon encouraged Menius to come join him at Wittenberg. The two would remain friends for life (and much later, Menius’ son would marry Melanchthon’s granddaughter.) “He became vicar in Mühlberg near Gotha in 1523, pastor in Erfurt in 1525, and superintendent of Eisenach 1529-1557. In 1541-1544 he served as temporary pastor in Mühlhausen, Thuringia, went to Gotha in 1546 and there succeeded his friend Myconius as superintendent of Gotha, without, however, giving up his position in Eisenach. Menius was a zealous promoter of the Reformation, taking an active part in the program of church inspection. In the last years of his life he participated actively in the theological disputes of the time. He became involved in a violent conflict with Amsdorf, whose thesis of the harm in good works he contested, defending the necessity of good works as evidence of the new life. This caused him to retire from his offices to the pastorate of the Thomaskirche in Leipzig, where he remained until his death on 11 August 1558.”(Schowalter, Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia).

I. Beuttenmüller (Melanchthon) 224; VD16 M 2494, Steiff/Tübingen Nachträge 491,2; II; VD16 G 1411; III.: VD16 B 3523