Steps to the Temple, The Delights of the Muses and Carmen Deo Nostro. By Ric. Crashaw, sometimes Fellow of Pembroke Hall, and late fellow of St Peters Colledge in Cambridge. The 2nd Edition.

London: In the Savoy, Printed by T.N. for Henry Herringman at the Blew Anchor in the Lower Walk of the New Exchange. 1670.

Price: $8,500.00

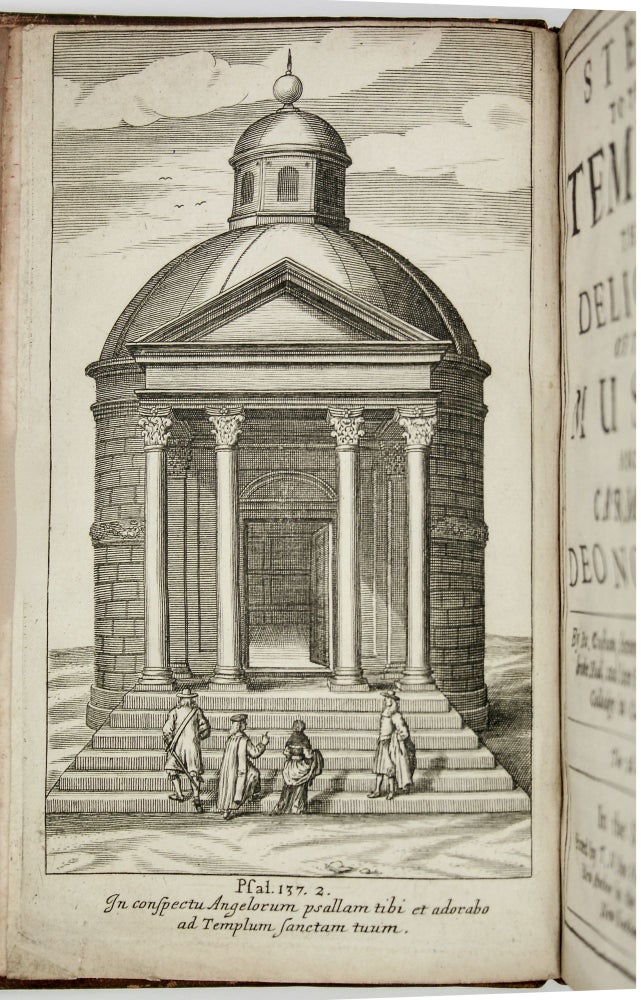

Octavo: [16], 112, 115-208, [2] p., [1] leaf of plates. Collation: A-O8 (O8 blank and present.) With an added, engraved frontispiece of the temple.

THIRD EDITION of “Steps to the Temple”.

Contemporary English calf, upper joint cracked. Complete with the engraved frontispiece. Provenance: Richard Heber, his sale 1834, to Britwell Court; Richard Jennings.

This collection of Crashaw’s poetry comprises the third edition (not the second, as the title states) of his “Steps to the Temple” (first 1646), the third edition of “The Delights of the Muses” (first edition 1648) and the second edition of the posthumous “Carmen Deo Nostro…Sacred Poems” (first edition 1652). "The Delights of the Muses” and the "Carmen Deo nostro" each has a divisional title page on leaves F8r and K5r respectively.

Along with Donne, Herbert and Marvell, Crashaw was one of the most important of the Metaphysical poets. "Compared with one another, Crashaw represents more of Donne's ecstasy, and Herbert more of his reason" (George Williamson). The son of a Puritan clergyman who eventually converted to Catholicism, Crashaw is best known for the intensity of his religious poetry.

This volume contains Crashaw’s best-known poems: "The Weeper", "Wishes: To his (supposed) Mistresse", and his “Hymn to Saint Teresa”, which provided the inspiration to Coleridge’s "Christabel". Also included is Crashaw’s poem in praise of George Herbert, “On Mr. George Herberts Booke entituled The Temple of Sacred Poems, sent to a Gentlewoman.”

“It is certain that Crashaw's English poetry was mostly written during his years in Cambridge. He wrote both on secular as well as sacred themes, but it is for his devotional poetry that he is rightly best remembered. His poetry was published in Steps to the Temple: Sacred Poems, with other Delights of the Muses by the royalist publisher Humphrey Moseley in 1646, with an expanded edition in 1648. As the title indicates Crashaw is presented as heir to George Herbert, another poet with Cambridge roots. But the styles of the two poets are different. Crashaw's devotional celebrations focus on believers as part of a large congregation, adding their voices to a chorus that stretches across liturgical history.

“A number of his poems originate in well-known medieval hymns, which he adapts rather than translates precisely. Crashaw has a preoccupation with female saints (the Virgin, Mary Magdalen, St Teresa), and this has generally supported a view of his Roman Catholicism. His thorough devotion to the Virgin, including accepting a version of her Assumption, would certainly have been frowned on by many within the English church, while St Teresa is one of the most celebrated of Counter-Reformation saints…

“Crashaw's poetic voice is a conspicuous one in English and possesses an exuberant, often ecstatic quality that builds over many lines, celebrating an emotional excitement that greatly surpasses the tenor of the scriptural or medieval texts on which the poems are often founded. Crashaw's version of the medieval ‘Sancta Maria dolorum’ readily exemplifies this. Imploring Mary, witnessing her son's crucifixion, to teach the poet an appropriate fervour to share in the event, he asks that the poet, the Virgin, and by implication the reader may ‘study him so, till we mix / Wounds; and become one crucifix’, and concludes with a desire for an emotional merging that sees him become the child suckling on his saviour.

“Much of Crashaw's English writing, both sacred and secular, builds on the epigram, the genre in which he gained his initial reputation… In his longer poems Crashaw frequently writes what can virtually seem a series of extended epigrams. For instance, each of the thirty-one stanzas of ‘The Weeper’, Crashaw's poem on Mary Magdalen, is effectively a separate epigram commemorating the penitent saint's tears. This allows the poet full exercise in varying rhetorical exaggeration and invention around a theme."(Thomas Healy, “Richard Crashaw” ODNB)

Carmen Deo Nostro:

Published posthumously, "Carmen Deo Nostro" comprises 33 English poems. The verses were written after Crashaw had fled England; the collection was first printed in 1652 at Paris. The “Carmen” includes Crashaw’s famous “Flaming Heart, Upon the Book and Picture of the Seraphical Saint Teresa ” (also known as his third “Teresa poem”), which was inspired by a painting of the saint and a 1642 English translation of the life of St. Teresa. It completes the Teresa poem cycle (“arguably, his most sublime works”) begun in the “Steps”.

Crashaw dedicated these poems to the Countess of Denbigh who had “used her influence to persuade the queen in early September 1646 to recommend Crashaw to the pope. The poet expressed the ardent gratitude of the Roman convert by entrusting his poems to Thomas Car for a new Catholic volume of his verse, Carmen Deo Nostro, and by ensuring that this volume, which was published posthumously in 1652, would be dedicated to the countess "in acknowledgment of her Goodnes & Charity" and in hopes of her own imminent conversion.

"The Flaming Heart," which completes Crashaw’s Teresa trilogy, alludes to a 1642 English translation of her life. It is the most intricate of his tributes to the saint. The poet opens with the commanding voice of church authority:

Readers, be rul'd by me; and make

Here a well-plac't and wise mistake,

You must transpose the picture quite,

And spell it wrong to read it right[.]

“His initial dispute is with the painter who drew a crude and childish illustration of the saint pierced through the heart by the dart of the seraphim. As a poet, Crashaw upheld the traditional superiority of the word to the picture in conveying such inner mysteries; but, as a painter himself, he was praised in Car's "Epigramme" (1652) for the "holy strife" between his pen and pencil as to "Which might draw vertue better to the life." Crashaw thus proposes to correct the painter's misconstruction with his own writer's pen and, in particular, to address the gender misconceptions that have led the artist to mock "with female FROST love's manly flame" by painting "Some weak, inferiour, woman saint." In the second section of the poem, which begins around line 69, he strives to reproduce Teresa's flaming heart. This heart personifies that which he must bring about in his own "hard, cold, hart," a spiritual transformation of self described in Galatians as a transformation in which "there is neither male nor female," neither parent nor child, strong nor weak, active nor passive, "for ye are all one in Christ Jesus." In the magnificent entreaty that culminates the poem, Crashaw invokes not only "all the eagle in thee, all the dove" but the pious memory of his own parents. He also concedes that both the verbal and the visual image fade away before Teresa's indescribable communion with God: "By all of HIM we have in THEE; / Leave nothing of my SELF in me." Though, in conclusion, he effaced himself and his art before the woman saint, he did not wish to dwell on Teresa so much as on Christ, who dwelled in her heart.”(Maureen Sabine, University of Hong Kong).

Wing C 6838; Grollier, Wither to Prior # 234