Les Plus Beaux Monuments De Rome Ancienne. Ou Recueíl Des Plus Beaux Morceaux de L'Antiquité Romaine Qui Existent Encore: Dessinés Par Monsieur Barbault Peintre Ancien Pensionnaire Du Roy a Rome, Et Gravés, en 128 Planches Avec Leur Explication.

Rome: Chez Bouchard et Gravier Libraires François rüe du Cours près de Saint Marcel, de l'imprimerie de Komarek, 1761.

Price: $16,000.00

Large Folio: 51 x 35.5 cm. VIII, 90 pp. Collation: [π]1, [a]-[c]1, A-Z, Aa-Yy1. With 73 added plates. Complete.

FIRST EDITION. A fine copy in contemporary calf.

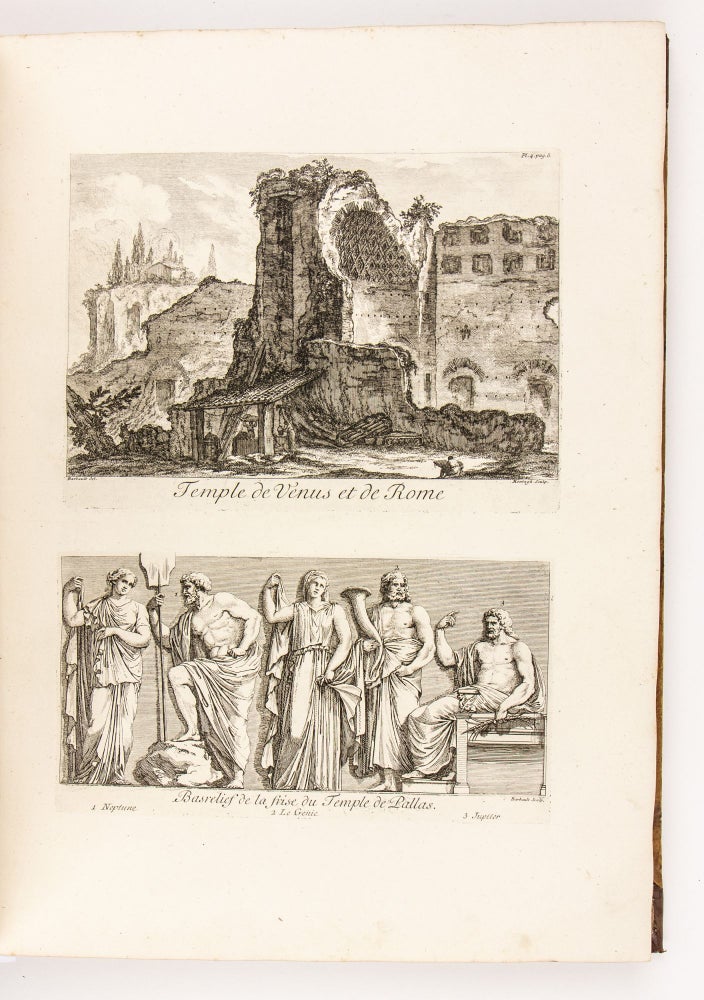

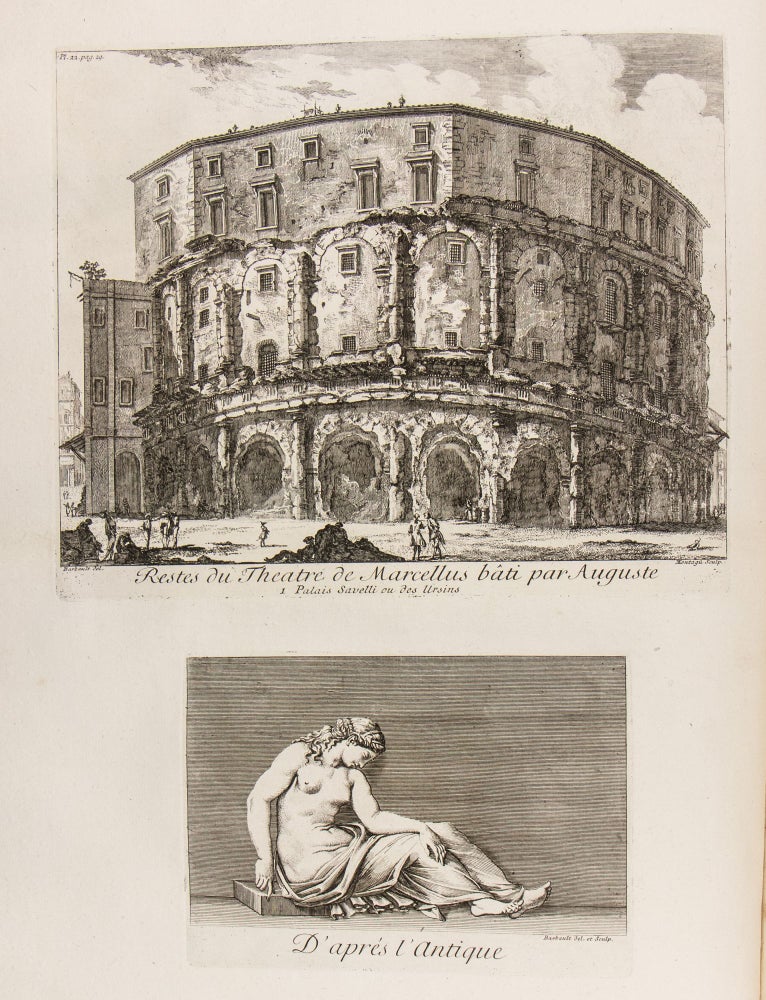

Magnificently illustrated with 73 etched and engraved plates comprising 88 half-page and 29 full-page images of ancient Roman architecture and sculpture. These were designed by Barbault (83 engravings), Carlo Nolli (1), and L. Bufalino (1) and engraved by Barbault (56), Domenico Montagù (52), Giuseppe? Bouchard (6), and Freicenet (4). The title page bears an etched and engraved vignette, the text is further illustrated with an engraved head-piece for the dedication and 9 engraved illustrations of ancient bas-reliefs and sculptures as tail-pieces.

The French artist Jean Barbault arrived in Rome in 1747 and quickly became involved with the circle of Piranesi, with whom he worked on the “Varie Vedute di Roma Antica e Moderna” and for whose “Antichità Romane” he contributed figures for 14 plates “thus becoming one of the few official collaborators” of Piranesi. Barbault’s own views appeared 7 years after his collaboration with Piranesi. The success of Barbault’s views was “largely due to the great fashion for large Roman views created by Piranesi’s publications. The overlapping questions of plagiarism and influence are quite vivid, since not only were Piranesi and Barbault both collaborators and rivals (Barbault died too young to present a real threat), but, more important, in Giovanni Bouchard they briefly shared a publisher as well. It has been persuasively suggested (Rosenberg 1976) that Bouchard promoted Barbault as a rival after Piranesi left to set up his own publishing enterprise and that Barbault became Piranesi’s most feared pasticheur.

“‘Les Plus Beaux Monuments De Rome Ancienne’ was dedicated by the publishers to Jean-François de Rochechouart, bishop of Laon and ambassador to the Holy See. The text accompanying the plates is in French. Many of the plates were not only drawn by Barbault but also engraved by him. Among these the small vignettes, mostly of low-relief sculpture, are extremely effective. The larger topographic views, made mostly by the obscure Domenico Montagù, are etched in an airier manner that seems almost Venetian, suggesting that this may be a graphic polemic against Piranesi. The collection is divided into two parts; the first part is about architecture and the second about sculpture. The architectural section is organized according to building types, such as temples, triumphal arches, theatres, columns and obelisks, baths and aqueducts, and tombs and altars.

“Barbault’s presentation and framing of views and fragments of sculpture are extraordinarily tactile and appealing. Many of his sculptural remains are inscribed on larger, irregularly shaped ‘stone’ fragments, a method- also employed by Piranesi- that is supremely effective in suggesting loss and the melancholy passage of time that inevitably destroys human work. The plan of the Pantheon, inscribed on such an irregularly shaped block, is a conceit that aligns Barbault’s own representation with the ruins of antiquity themselves; it was adopted by Piranesi in his plan of Santa Costanza, incidentally also a circular building. The text is peppered throughout with references to the historians of Rome, such as Pliny the Elder, Alessandro Donati, Bernard de Montfaucon, and Famiano Nardini, as well as to Piranesi… Barbault also engages with amateur archaeologists, such as the architect Andrea Palladio, whose reconstruction of the Temple of Antoninus and Faustina he challenges. Especially atmospheric and romantic is the moody full-page plate of the Temple of Concord. The inscriptions on the Arch of Septimius Severus are transcribed in the text, the carving on the Arch of Titus praised, and the arch of Constantine execrated for the low quality of its sculpture. Barbault points out his own contributions, for instance, his discovery of the altar in the Theater of Marcellus, while equitably saluting his rival Piranesi who had illustrated the foundations of the theater.

“The persuasive images are enhanced throughout by the unassumingly helpful text. For the Colosseum, Barbault refers to Carlo Fontana, Antoine Desgodetz, and Scipione Maffei as his sources. Explaining that the name of the building was taken from the large statue of Nero placed nearby and that the arena was named after the sand that covered it in antiquity, Barbault pointedly lists the Roman palaces (Venezia, Farnese, among others) whose construction turned the Colosseum into a stone quarry. His views were commercially successful, and in many ways he can be said to have completed the views of Piranesi, the dominant topographer who established lasting standards.”(Pollak, Millard IV, pp. 42-44).

La Cicognara 3593; Fowler 37; Millard IV, no. 13; RIBA, Early Printed Books, 184