Fragmenta aurea. A collection of all the incomparable peeces, written by Sir John Suckling. And published by a friend to perpetuate his memory. Printed by his owne copies

London: Printed [by Ruth Raworth and Thomas Walkley] for Humphrey Moseley, and are to be sold at his shop, at the signe of the Princes Armes in St Pauls Churchyard, 1646.

Price: $4,500.00

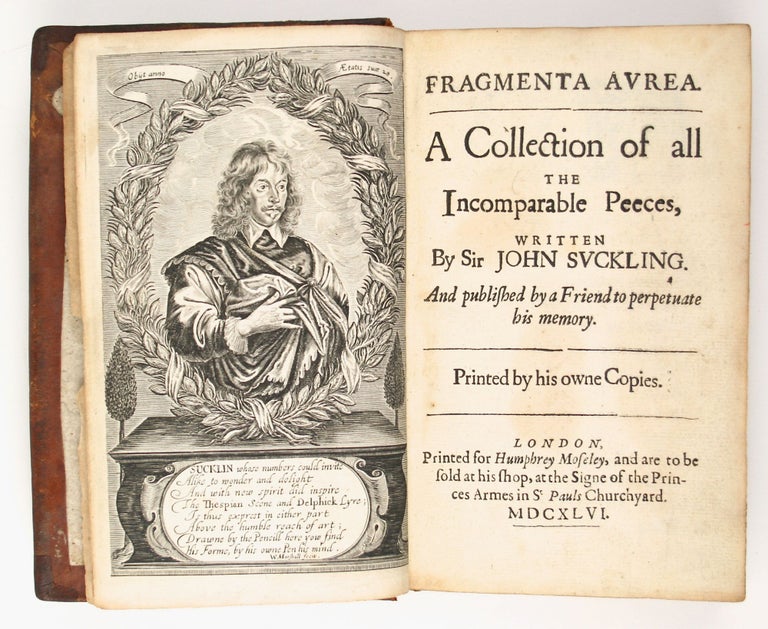

Octavo: 18.2 x 11.3 cm. [8], 119, [7], 82, 64, [4], 52 p. With an engraved portrait (A1v.) by William Marshall. A4, A-G8, H4; A-E8, F4; A-D8; A-C8, D4.

FIRST EDITION, first state of the title, with first line of title all in uppercase, period after "Churchyard" in the imprint, and rule under the date; Leaf A3v line 16 reads "allowred."

A very fine, crisp copy in contemporary blind-ruled calf with minor wear to the head of the spine and the very bottom of the hinge.

The engraved frontispiece portrait (A1v) is signed: “W. Marshall fecit.” With separate title pages for “Poems &c.”, “Letters to Divers Eminent Personages” and “An Account of Religion” with continuous register and pagination. Separate dated title pages with continuous register and pagination for “Aglaura. Presented ... in Black-Fryers” and “Aglaura. Represented at the Court”. The two remaining works, “The Goblins, A Comedy” and “Brennoralt, A Tragedy” with separate dated title pages, register, and pagination.

First edition of the most important volume of Suckling’s work, comprising his poems, letters, the tragedies Aglaura (1637, rev. 1638) and Brennoralt (late 1639?), and the comedy The Goblins (1638–1641), and the “An Account of Religion.”

“Suckling made his mark as a poet, playwright, and belletrist, but he was a writer mainly by avocation, and by second nature. He was first and last a wit and a courtier to Charles I, being occupied mainly as a gentleman officer, socio-political observer, gamester, amorist, and marital fortune seeker—often impetuously and not always successfully.

“First known as a gallant and gamester, Suckling became famous also as a writer. He somehow found time to write much, and often well, in a range of genres, his œuvre extending to seventy-eight poems (c.1624–1641); four plays, The Sad One (c.1632, unfinished), Aglaura (1637, rev. 1638), The Goblins (1638–1641), and Brennoralt (late 1639?); An Account of Religion by Reason (1637); several political tracts; and over fifty surviving letters, a few of literary genre and most of literary quality. His earliest known writings are religious poems written probably about 1624, when he was fifteen: St Thomas figures in two of these, and the concern with faith and doubt anticipates An Account of Religion.

“The years 1637 and 1638 were Suckling's literary anni mirabiles. In 1637 he wrote the tragedy Aglaura, the Account of Religion, and ‘The Wits’ (‘A Sessions of the Poets’ in Fragmenta aurea, 1646), with its witty but also probing fictional contest between Davenant, Thomas Carew, Ben Jonson, and others; the queen is present, and Apollo the god of poetry himself is judge. No one has better expressed Suckling's character than himself in this poem in a genre of his own invention—the trial for the bays—imitated by many, including Dryden in his Essay of Dramatic Poesy.

Suckling next was call'd, but did not appear,

And strait one whisperd Apollo in's ear,

That of all men living he cared not for't,

He loved not the Muses so well as his sport;

And prized black eyes, or a lucky hit

At bowls, above all the Trophies of Wit.

(‘A sessions of the Poets’, 73–8)

“While ‘The Wits’ was being sung to the king on a hunting expedition to the New Forest in August 1637, only 60 miles away Suckling was writing his Account of Religion in Bath, where he had ‘had a Cart-load of Bookes carried downe … 'Twas as pleasant a journey as ever men had; in the height of a long Peace and luxury, and in the Venison Season’ (Brief Lives, 289)—the last such retreat for Suckling and many another, after 1638.

“Suckling's other major poem, in the novel genre of rustic epithalamion, is ‘A Ballade upon a Wedding’ (‘I tell thee Dick, where I have been’), written probably for the marriage of John, Lord Lovelace, and Lady Anne Wentworth on 11 July 1638. In this, a fashionable town wedding is described by a cottage rustic in country terms and perspective but also with sensitivity, perceptiveness, and a keen levelling humour, a sustained balancing act between dramatis personae and poet especially deft in conclusion: what the bride and groom did at bedtime:

who can tell?

But I beleeve it was no more

Than thou and I have done before

with Bridget, and with Nell.

“Rough times ended Suckling’s life prematurely: heir at eighteen and prodigal as soon, he died at thirty-two in Paris, penniless and probably a suicide; the Commons judged him a traitor to parliament, to royalists he was a martyr before the king. His works circulated widely in manuscript during his lifetime and, published posthumously by Humphrey Mosely, were bought in large numbers and read with eagerness and admiration during the interregnum and after. His stature as a poet—and literary arbiter deliciarum—was at its highest during the Restoration.

“It is perhaps helpful to view Suckling in a longer perspective than that of Caroline court culture or modern academic fashions. Although Suckling is not of the comparable stature of Catullus, Horace, and Ovid, their poetry and ethos provide a liberating context for viewing him, and not just because Catullus died young, Horace never married, and Ovid perished in exile, but because all four live in their poetry and all have the power to move our emotions memorably from beyond the grave with their distinctive curiosa felicitas in verse.”(Clayton, ODNB).

Wing S6126; ESTC R15688; Hayward 84; Pforzheimer 996; Studies in Bibliography 165; L. A. Beaurline and T. Clayton, "Notes on Early Editions of Fragmenta Aurea," Studies in Bibliography 23 (1970), pp. 165-170