Letters to Severall Persons of Honour: Written by John Donne, Sometime Deane of St Pauls London. Published by John Donne Dr. of the Civill Law.

London: Printed by J. Flesher, for Richard Marriot, and are to be sold at his shop in St Dunstans Church-yard under the Dyall. 1651.

Price: $12,000.00

Quarto: 17.5 x 13 cm. [5] (title page plus dedicatory epistle), 318 pp. Collation: A4 (-blank leaf A1) B-Z4, Aa-Ss4 (with blank leaf Ss4 present). With the added engraved portrait.

FIRST EDITION, FIRST ISSUE.

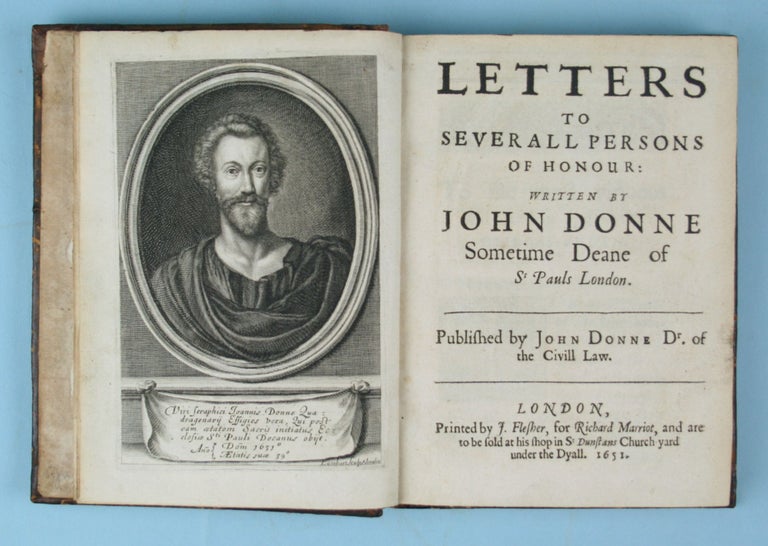

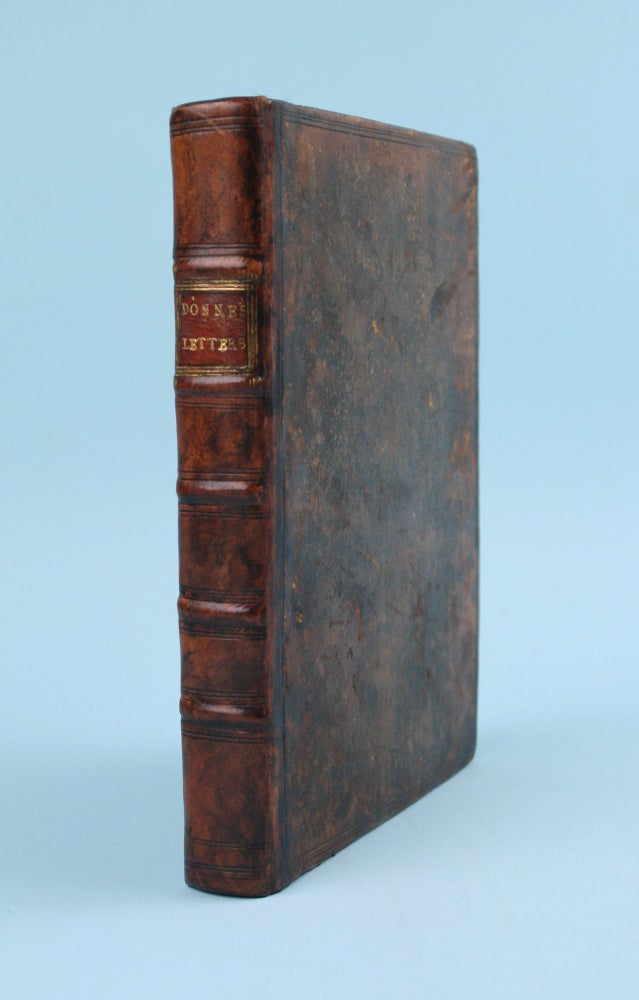

With the fine engraved portrait of Donne by Pieter Lombart bound opposite the title page. This copy is bound in contemporary English calf, rebacked so discreetly that it is impossible to see where the leather has been joined. The original gilded red morocco spine label is preserved and a double blind-ruled fillet frames the boards. The engraved portrait and text are in excellent, crisp condition. A truly fine copy.

Provenance: This copy was once the property of the author and essayist Sir Thomas Pope Blount (1649-1697) and bears his familiar ms. note “Tittenhanger library” on the free endpaper. Blount inherited the Tittenhanger estate in Hertfordshire in 1678. In his “Essays on Several Subjects” (1692), Blount wrote: “If learning happens to be in the possession of a Fool, ‘tis then but a Bawble, and like Dr. Donne’s Sun Dial in the Grave, a trifle, and of no use.” Blount also devoted several pages to Donne in ‘De Re Poetica’ (1694). This copy also bears the bookplate of the bohemian Evan Morgan, the last Viscount Tredegar (d. 1949).

Published posthumously by the poet’s son, John Donne (1604-1662), this collection contains 129 letters, written between December 1600 (a year before Donne's marriage to Anne More) and March 1631 (two months before his death.)

"'In no other kind of conveyance,' Donne once told Goodere, 'can we find so perfect a Character of a man as in his Letters'. These letters provide valuable information about Donne's situation and frame of mind at the time of the poems that many readers consider his greatest achievements -the 'Anniversaries', the 'Holy Sonnets', many of the verse letters and 'A Litanie'. Moreover, the letters provide an even fuller account of the periods of intense mental and physical duress during the composition of Donne's equally important prose works -'Biathanatos', 'Pseudo-Martyr', his polemical support of the Oath of Allegiance, 'Devotions' and many of his sermons.

"An even more impressive (and constant) feature conveyed by the letters is the picture of Donne the family man. Here we see the loving husband who bemoans that he has transplanted his wife Anne 'into a wretched fortune' and who reflects at the time of one of her illnesses that he 'should hardly have abstained from recompensing for her company in this world, with accompanying out of it.'… Here also are those brief personal touches that one would expect from 'conveyors of friendship' -glimpses of his nervousness at being commanded to preach before King Charles I for the first time, that he has neither the 'ambition, nor design upon the style' to pursue the law as his 'best entertainment', of his preference for life in the city and, as always, his delight in self-criticism: 'I may die yet, if talking idly be an ill sign.'"(M. Thomas Hester)

"Like his poems, Donne’s letters paint the brilliant and insolent young man; the erudite and witty -but troubled and melancholy- suitor for court favor and office; the ascetic and fervent saint and preacher. And this is their chief interest. For some time, Donne held the position, almost, of the English épistolier, collections of the ‘choicest conceits’ being made in commonplace books from his letters as well as his poems. But they were not well fitted to teach, like Balzac’s, the beauty of a balanced and orderly prose, though they far surpass the latter in wit, wisdom and erudition. Their chief interest is the man whom they reveal, the characteristically renascence ‘melancholy temperament,’ now deep in despondence and meditating on the problem of suicide, now, in his own words, kindling squibs about himself and flying into sportfulness; elaborating erudite compliments, or talking to Henry Goodere with the utmost simplicity and good feeling; worldly and time-serving, noble and devout—all these things, and all with equal sincerity." (Cambridge History of English and American Literature, Vol. IV, Ch. 11.).

Pforzheimer, 295; Wing D1864; Keynes 55