Thoukudidou tou olorou peri tou Peloponnesiakou polemou biblia okto (Graece). THVCYDIDIS De Bello Peloponesiaco Libri VIII. Iidem Latinè, ex interpretatione Laurentii Vallæ, ab Henrico Stephano recognita. Secunda Editio.

Geneva: Excudebat Henricus Stephanus, 1588.

Price: $9,500.00

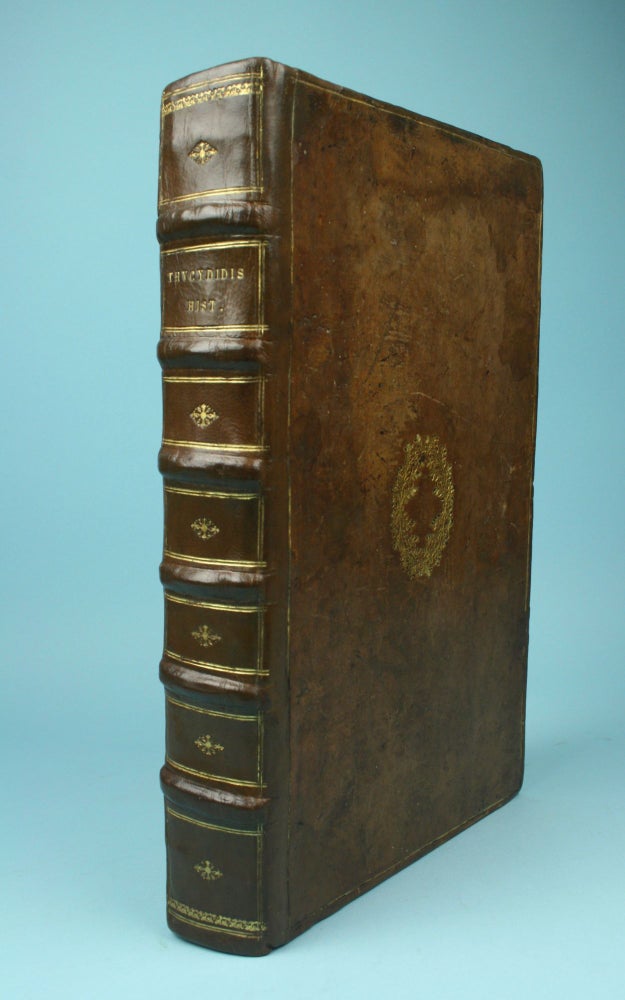

Folio: 32.2 x 21 cm. Collation: ¶6, ¶¶4, a-z6, aa-zz6, aaa-nnn6, ooo4.

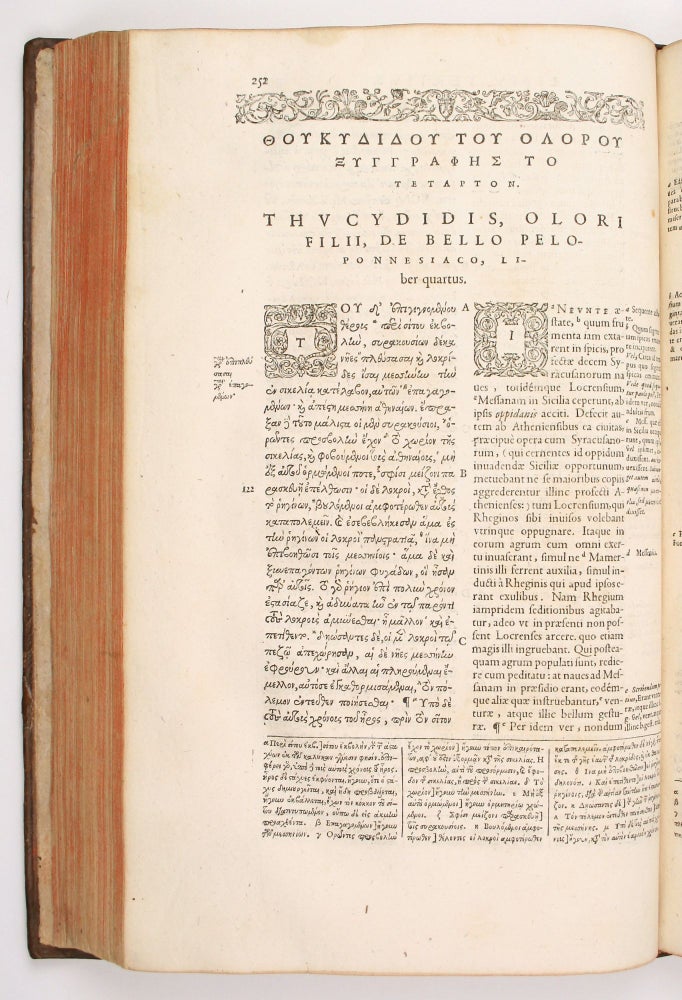

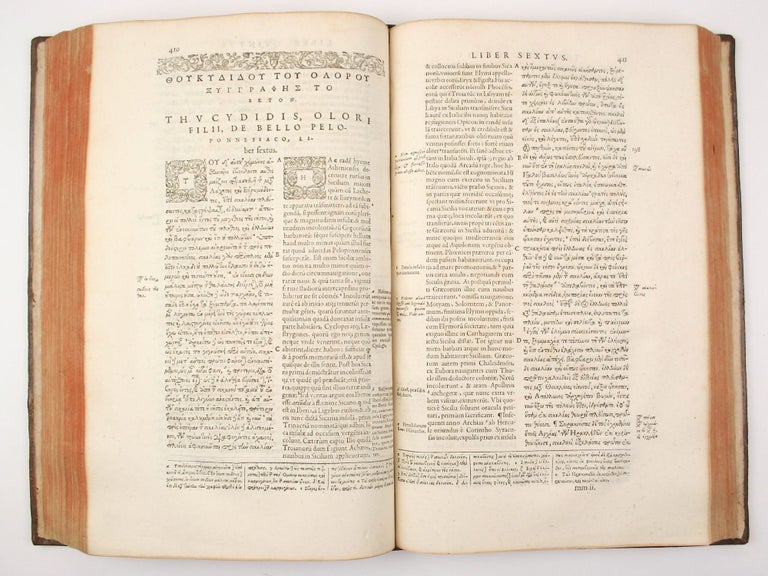

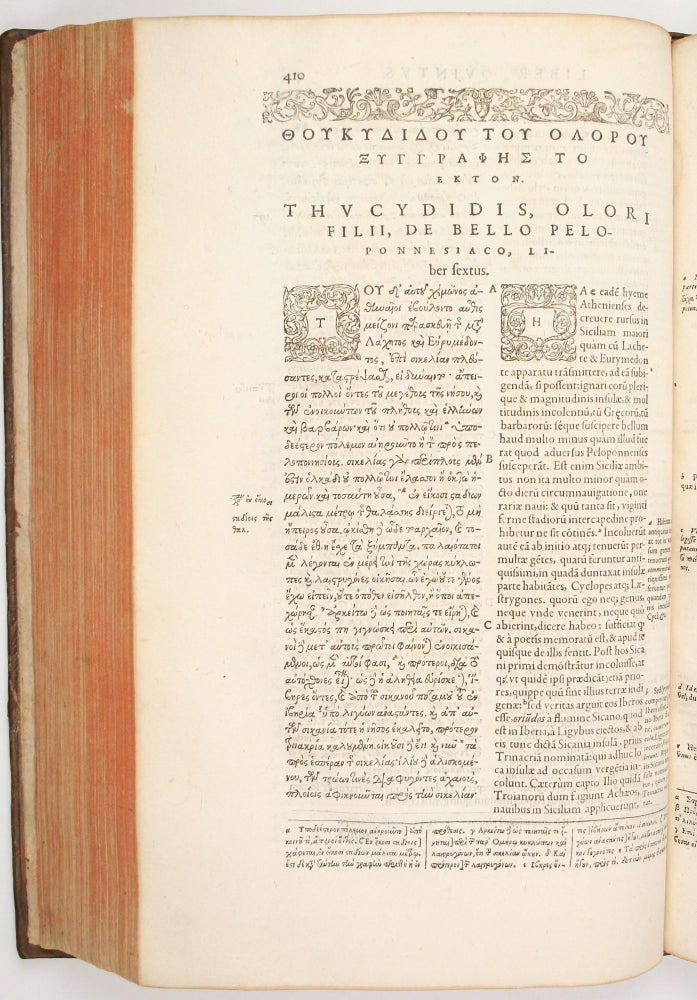

SECOND ESTIENNE EDITION, corrected by Estienne and with numerous additions. Printed in two sizes of the ‘grecs du roi’ types of Claude Garamond. There are numerous historiated initials and decorative head- and tail-pieces. The Estienne "Noli altum sapere" device appears on the title page.

Bound in contemporary calf, rebacked. The boards are framed by a single gold fillet. Central, wreath-like cartouches, also gilt, are stamped at the centers of both boards. The text is in very good condition, with good margins. There is, however, a bit of worming affecting the text in the first part.

Second Estienne edition, generally considered the best sixteenth century edition, of Thucydides’ history of the Peloponnesian War. The war was fought from 431–404 BC “between the two leading city-states in ancient Greece, Athens and Sparta. Each stood at the head of alliances that, between them, included nearly every Greek city-state. The fighting engulfed virtually the entire Greek world and it was properly regarded by Thucydides as the most momentous war up to that time. With Athens’ defeat . . . the most culturally advanced Greek state was brought into final eclipse.” (Britannica)

"For this new edition Estienne has corrected the Greek text and scholia, as well as further revised Lorenzo Valla's Latin translation, which is now printed on the same page with the Greek text, in parallel columns, while the Greek scholia are printed at the foot of the page. Estienne has also added marginal concordances to his first edition. Among the other important additions are Estienne's ‘Proparasceue’ (Preparation) to the reading of the Greek scholia, which is, to this day, a most valuable exposition of the special vocabulary and technical terminology used by the Greek scholiasts; his annotations on the text and scholia of the first two books (Renouard, as well as Carter and Muir in PMM, wrongly attribute these annotations to Isaac Casaubon); the Thucydidean Chronology of David Chytraeus, and the Greek Life of Thucydides by Marcellinus, with a Latin translation by Casaubon." (Quoted from Schreiber's "The Estiennes")

"The standards and methods of Thucydides as a contemporary historian have never been bettered. Thucydides has been valued as he hoped; statesmen as well as historians, men of affairs as well as scholars, have read and profited by him"(PMM 102).

“Thucydides kept rigidly to his theme: the history of a war—that is, a story of battles and sieges, of alliances hastily made and soon broken, and, most important, of the behaviour of peoples as the war dragged on and on, of the inevitable “corrosion of the human spirit.” He vividly narrates exciting episodes and carefully describes tactics on land and sea. He gives a picture, direct in speeches, indirect in the narrative, of the ambitious imperialism of Athens—controlled ambition in Pericles, reckless in Alcibiades, debased in Cleon—ever confident that nothing was impossible for them, resilient after the worst disaster. He shows also the opposing picture of the slow steadiness of Sparta, sometimes so successful, at other times so accommodating to the enemy.

“His record of Pericles’ speech on those killed in the first year of the war is the most glowing account of Athens and Athenian democracy that any leading citizen could hope to hear. It is followed (in, of course, due chronological order) by a minutely accurate account of the symptoms of the pestilence (“so that it may be recognized by medical men if it recurs”) and a moving description of the demoralizing despair that overtook men after so much suffering and such heavy losses—probably more than a quarter of the population, most of it crowded within the walls of the city, died.

“Equally moving is the account of the last battles in the great harbour of Syracuse and of the Athenian retreat. In one of his best-known passages he analyzes by a most careful choice of words, almost creating the language as he writes, the moral and political effects of civil strife within a state in time of war. By a different method, in speeches, he portrays the hard fate of the town of Plataea due to the long-embittered envy and cruelty of Thebes and the faithlessness of Sparta, and the harsh brutality of Cleon when he proposed to execute all the men of the Aegean island city of Mytilene. Occasionally, he is forced into personal comment, as on the pathetic fate of the virtuous and much-liked Athenian Nicias.

“He had strong feelings, both as a man and as a citizen of Athens. He was filled with a passion for the truth as he saw it, which not only kept him free from vulgar partiality against the enemy but served him as a historian in the accurate narrative of events—accurate in their detail and order and also in their relative importance. He does not, for example, exaggerate the significance of the campaign he himself commanded, nor does he offer a self-defense for his failure. Characteristically, he mentions his exile not as an event of the war but in his “second preface”—after the peace of 421—to explain his opportunities for wider contacts.

By the end of the 4th c. BC “the philosopher Theophrastus coupled Thucydides with Herodotus as a founder of the writing of history. Little is known of what the scholars of Alexandria and Pergamum did for his book; but copies of it were being made in considerable numbers in Egypt and so, doubtless, elsewhere, from the 1st to the 5th century AD. By the 1st century BC, as is clear from the writings of Cicero and Dionysius (who vainly disputed his preeminence), Thucydides was established as the great historian, and since that time his fame has been secure.” (Britannica).

Schreiber 216-217; Renouard 152-53, 4; Moeckli 124; Hoffmann III, 749; Printing and The Mind of Man, 102.